Harriet Pattison melds correspondence and memoir to explore her role in the life and work of Louis Kahn.

By JoAnn Greco

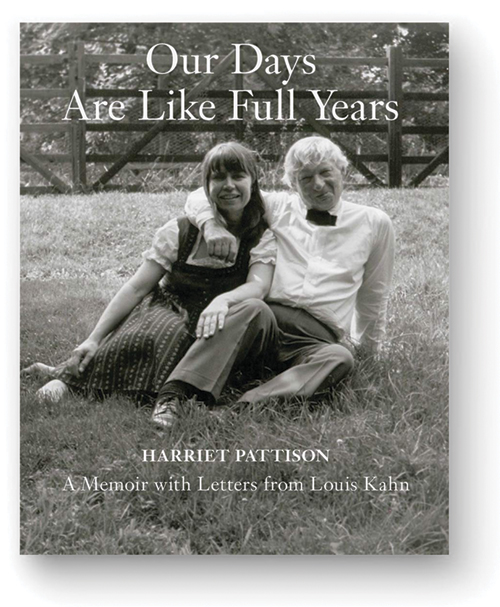

Our Days Are Like Full Years

By Harriet Pattison

Yale University Press, 448 pages, $45

In her new memoir, Our Days Are Like Full Years—a title taken from one of many romantic, over-promising communiques that Louis Kahn Ar’24 Hon’71 sent her—Harriet Pattison GLA’67 presents a contemporaneous look at the celebrated architect’s work during the 1960s and ’70s. Kahn scholars and enthusiasts will lap up the wealth of drawings and insights, but there’s a lot more here. After living and working almost literally in Kahn’s shadow for decades—she was his mistress and muse for the last 15 years of his life, as well as an occasional coworker who at one point designed major landscape projects for him while squirreled away in a room that was little more than a closet—this is Pattison’s time to make her presence felt.

Speaking by phone from her home in a converted barn in suburban Philadelphia, Pattison says that when she first revisited the correspondence she’d set aside for years, her “intention was to show what was going on with Lou’s work during this period through his eyes.” And this volume offers a rich trove of letters, postcards, telegrams, and drawings Kahn sent her over the years. But as she began her research—poring through the Kahn collection at Penn’s Architectural Archives and prodding her son with Kahn, Nathaniel, for his memories—Pattison began to sense that as much as she shunned the spotlight, her voice was necessary. With no missives of her own to review—“I’m quite grateful that they’ve disappeared,” the 92-year-old says with a chuckle—she decided to add the beautifully written, keenly observed commentary that drives this book.

Of course, there’s a lot of Lou because, well, he was a lot. His letters bristle with vim and vigor, often filling every inch of the page. Illustrations abound, as do photos of Harriet and Lou through the years (she favors pageboys and pinafores, he, wilted suits and white shirts). Especially peripatetic during these years, Kahn dispatched many of these notes from abroad.

The man was a great travel writer, his verbal sketches of the people he encountered as sharply drawn as any architectural elevation. “I went today to a Yemenite village,” he writes from Tel Aviv in the summer of 1963. “[T]he most ancient looking man I ever saw … sat at a bench over his work … A pipe, about 8 feet long, was constantly in his mouth. No smoke came out of it or out of his mouth. He inhaled it all.” The standard gripes of the creative genius (“All of the ideas I gave them … are on the plan in the wrong place … It’s sickening!”) and the persistent plaints of delayed flights and payments, of lost baggage and commissions, regularly find Kahn in a blue mood. Yet again and again, with effervescent resilience, he adroitly recovers with whimsy or self-deprecation. Poetic introspection is a frequent visitor, too: “Here now almost the whole of me is out of me,” he writes. “The tiniest of thread holds on to me”—catnip for the sensitive, artistically inclined Harriet.

Born in Chicago, one of six surviving children, Pattison showed an early interest in architecture and music, and the book begins with her at Yale, in the graduate drama program. One snowy day, she encounters Kahn. To the 25-year-old Harriet, he’s simply an older (by 27 years) man in need of a hand navigating the slippery sidewalk. When she and her friends invite him to join them for coffee, he holds court but doesn’t disclose his identity. Pattison recalls writing in her journal: “I met an amazing man.”

A few years later it’s 1958 and she’s in Philadelphia, studying under a teacher from the Curtis Institute of Music and enjoying a “sweet, courtly romance” with, of all people, the soon-to-be-celebrated architect Robert Venturi Hon’80. At a holiday party, they bump into Kahn. Then he turns up at a party she herself is hosting, and soon afterward they meet again at an architectural event. At the end of that evening, Bob and Lou and Harriet meander through Rittenhouse Square: the two men being geniuses together as she chimes in now and then. When Harriet and Lou catch each other’s eye she feels a “rush of excitement”—and we’re off.

Harriet sends Kahn an invitation to dinner. His response, the first of the letters she reprints here, is brief but lushly romantic. “Dearest Harriet, I received your note. It is so deeply good. Always it will be a delight to meet you wherever.” By July, professions of love have been exchanged. Letters and postcards pour in, but it isn’t long before Pattison starts questioning the relationship. “What kind of a future was there in this?” she recalls wondering. “I didn’t want to end like a character in an Edith Wharton story, stuck in a tiny apartment, the lover of a man who showed up at his convenience.” Still, she decides to quit her New York job and relocate to Philly in the hopes that Lou’s “someday, someday” talk might be realized.

When Kahn invites her to attend a Museum of Modern Art opening in his honor, she observes that his father, wife, daughter, and an ex-lover (the architect Anne Tyng Gr’75, with whom Kahn also had a child) hover around the star of the show. In a letter sent a few days afterwards, Lou writes to her: “It was so hard to feel your disappointment in not being able to talk to me freely. The delight of the few nights that we had alone before your leaving lingers … Only prying words make our meeting less.” In her narrative, Pattison assumes they’ve argued about her feeling treated as “just another person, one of many, in his life. His response felt like a subtle scolding. It was as if the doors and windows to the outer world might be shuttered, and that I would be kept in a secret place.” Passages like these underscore that this is Pattison’s story. Aspects of Kahn’s other goings-on—his home life with his daughter and wife, for example, or his sporadic visits to Tyng and their daughter—remain hidden.

Never bitter or sentimental, always moving and inspiring, Our Lives is ultimately about the awakening of a resolute and independent woman whose understanding of the tradeoffs she willingly entered into was, and remains, clear-eyed and uncompromising. “You can suddenly unlock all kinds of memories if you take the time to reflect,” Pattison says over the phone. “But even at the time, I felt that what was happening was untraveled territory. It was not how I expected my life to go.”

Certainly the idea of bearing a child out of wedlock—the news of which elicits a murmured “not again” from Kahn—wasn’t part of her plans. Determined to keep the child, Harriet reaches a turning point and, it seems, an unspoken understanding: Lou will be around, but not really. “I will try to get the where with all [sic] soon,” he writes in a postscript to an October 1962 letter that primarily deals with his antics at a rollicking party. She receives it a month before Nathaniel is born. Riding out her pregnancy at a friend’s house in Connecticut, Harriet waits for Kahn to send the promised money to help with the baby’s delivery. It never arrives.

During the next decade, Kahn’s career takes off; he crisscrosses the globe, dropping in occasionally with presents and promises for Harriet and Nathaniel (who would later explore his own experience of that relationship in the Oscar-nominated 2003 documentary My Architect [“Arts,” Jan|Feb 2004]). Kahn’s correspondence bursts with ideas and sketches for his major commissions, like the Salk Institute in La Jolla, California, as well as copious material detailing his unbuilt work. Looking back at all this, Pattison draws connections and notes possible inspirations linking the works. “The projects that weren’t built were especially original and stunning,” she says in conversation. “What he was aiming for with them was very significant and new.”

Among those unbuilt works was Four Freedoms Park on New York City’s Roosevelt Island. Featuring Pattison’s most complete landscape contribution to a Kahn project, it was finally opened in 2012 [“Constructing a New Kahn,” Mar|Apr 2013]. By that point, Pattison, who never married, was winding down a 40-year solo practice, and the realization of this 1973 design triumphantly concludes the book. In the end, she has arrived: a fully-formed pioneer who knows her value not only in Kahn’s personal narrative, but in his professional oeuvre—and in her own mind.