A project to reissue Richard Saul Wurman’s classic, long-out-of-print 1962 volume of Louis Kahn’s art.

“There are a lot of wonderful books on Lou Kahn,” says Richard Saul Wurman Ar’58 GAr’59, referring to the iconic 20th-century American architect. “And if I was going to have just one book, it wouldn’t be mine.”

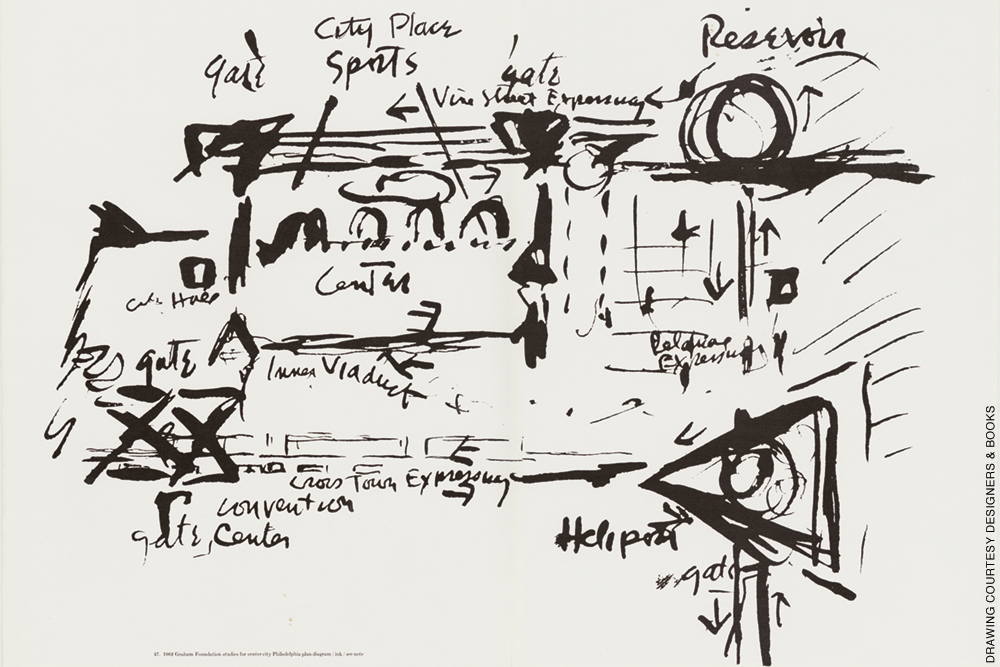

Wurman’s contribution to the Kahn canon was the 1962 volume The Notebooks and Drawings of Louis I. Kahn. Ranging from sketches of ancient ruins and European cityscapes, to pencil renderings of his own buildings (like the Richards Medical Research Laboratories at Penn), to conceptual designs for never-built proposals (like the architect’s radical plan to remake Center City Philadelphia), the book’s eclectic survey of Kahn’s freehand art won many admirers. And even if Wurman would pack a different volume for a proverbial desert island, his own would probably make the cut if he had a whole shelf to work with.

It has been out of print for decades, but this winter the publisher Designers & Books is launching the Louis I. Kahn Facsimile Project (louisikahn.com), a Kickstarter campaign to publish an exact replica, augmented by a reader’s guide to feature additional material, including some drawn from Penn Architectural Archives, most of which has not been published before.

Wurman recalls encountering Kahn for the first time in 1955 as an architecture student at Penn. “I saw this funny little man with a high-pitched, somewhat raggedy voice, and an ill-tied bow tie,” he remembers. “He had this reputation among students, but I’d never heard of him.” Wurman was captivated almost at once. “When he said something, it was so simple, and it was the truth. And I realized I had been brought up with people not telling truth—or not asking questions that elicit the truth.”

Eventually Wurman took a job in Kahn’s private practice, where one day he worked up the nerve to pitch his idea for a book.

“He said yes, which shocked me,” Wurman remembers. “He said, ‘Let’s go pick out the pictures,’ and he opened the drawers.” Then Wurman sprung the catch: he didn’t want Kahn to choose what to include; that would be Wurman’s job alone.

“I didn’t want any photographs, and I didn’t want any beautiful renderings,” Wurman says now. “I wanted developmental drawings. I wanted drawings that showed his process and his mistakes as he drew: the struggle. I’m very interested in failure and struggle as a way of moving forward.”

Kahn giggled, as Wurman tells it, and let his former student proceed on his merry way.

Why exactly did Wurman want to make precisely this kind of a book, with its jumble of quick sketches, handwritten notes, draft drawings of projects that were later refined, and grandiose ideas that were never built at all?

“So I could have it by my bed,” he says, with a simplicity borne of a deep love for Kahn that has never faded.

“Lou said to me once, ‘A good idea that doesn’t happen is no idea at all,’” Wurman elaborates. “But I don’t judge it the way Lou judged it. He had ideas that never got done that were still enormous contributions to the world of architecture. He never did Mikvah Israel, he never did the Meeting House at Salk, he never did the central synagogue in Jerusalem, he never did the Goldenberg House. He got them up to a certain point, and I think they’re still valued contributions.”

The Notebooks and Drawings of Louis I. Kahn did not feature those particular examples but was created in that spirit.

“This book should not be in competition with beautiful books, most of which are really pretty good,” Wurman says. “There’s no beautiful photographs, or anything sexy in that way. But there will be the thought in his drawings, the mistake, the notes he left on them for what to do next. That, to me, is fascinating. It’s much more alive than a photograph of a finished building.”—TP