Prelude to a life in sports broadcasting.

By Budd Mishkin

It was the worst of times. Fall had descended on 1985 and there was no Charles Dickens about it: the best of times may have dawned for others, but I was mired in only the worst. Four years out of Penn, I was out of work and lacking direction, cluelessly squeaking by with help from my folks. I was living in what New Yorkers called a railroad apartment, where you can stand at one end and see straight through to the other. I shared it with my oldest friend, Mark, and one of his friends, Danny. Danny was in school, Mark was underemployed, and I had nothing going at all. Beyond our cramped quarters the bachelor’s bacchanalia was in full swing. Wall Street was booming and the money seemed to be raining into every pocket but ours. As the daylight shrank and the cold set in, I’d look into Mezzaluna restaurant on Third Avenue, see all of the people having a great time, and wish them all … well, bad things. Our neighborhood commissary was a Chinese takeout place called Wok on Third. We’d order on Sunday night and leave enough to have leftovers on Monday. On lucky weeks, we still had food left for Tuesday night. Let the good times roll.

I’d come to New York that summer because some friends had offered to loan me their apartment in Brooklyn for a short spell, which I’d taken as a sign from God that I should leave my full-time radio job down the Jersey Shore. Once you’ve got New York’s real estate figured, I reasoned, everything else will follow. And it seemed to—at the start. I landed a summertime vacation-relief job writing news at the radio station WMCA. WMCA had been big in the 1960s, playing rock-and-roll and calling its deejays “The Good Guys.” Those glory days were long gone, but still, it was a job. I’d drive into Manhattan around 3 a.m., park about eight blocks from the station, and walk the remainder with an umbrella. Clear sky overhead? Didn’t matter. Carry an umbrella. I also cultivated the habit of talking to myself. That’s hardly unusual nowadays, in the era of earbuds and Apple watches. But in 1985 it was an excellent way to come off as a bit unhinged, and therefore best avoided. I doubt that I ever struck fear into the hearts of my fellow night owls. But I didn’t have any issues. Must have been the umbrella.

I worked from 4 a.m. until noon writing news copy for the Ralph & Ryan show. Hardly my dream job, but it was New York and I was learning. I was a good writer, not a great one, but I got the copy in on time and managed not to get the station sued. I thought it was going well, and was told as much by the station’s honchos. The demo tape I made for some on-air work landed with a thud, but otherwise I was cruising toward what seemed sure to become a full-time position. And so when August ended and the general manager said, “Thanks a lot, good job,” I was surprised. As was she when she saw my surprise, forcingher to once again explain that a summer vacation-relief job was exactly what it sounded like. And summer had ended, along with my time at WMCA.

September bled into October, and then November, which passed in its own turn, finding me still out of work. No job, no plan, no strategy.

Then, in early December, I got a phone call out of the blue from Morrie Trumble, an ABC Radio announcer I’d met over the summer. He explained that he had a service that provided ski reports for radio stations around the region. One of his announcers had just bailed on him. Was I interested? If memory serves, I copped a bit of an attitude with him. “Thank you very much, Mr. Trumble, but I’ve done news and sports. Ski reports?” By way of reply, he gently inquired if I was working. “Look,” he said, “it’s 100 bucks a week part-time: three hours every morning from your apartment. But it will get you on the air.” I will forever appreciate that piece of advice and the kind way Morrie offered it. “It will get you on the air.”

So began my career as a ski reporter. I didn’t know Killington from Stratton, but to my assigned 20 stations, I was a ski reporter. Morrie held a conference call with the announcers at 5:30 a.m. every weekday, updating us on the resorts: how much new-packed powder, how many trails open. Then, for the next three hours, I called radio stations.

There was nothing cool or suave about ski reports on the radio. They always went to 11. So I came out of the gate hollering at the top of my lungs. “Good morning Boston, welcome to the Morning Zoo 105 Ski Zone! It’s a great day for skiing!” For the record, it was always a great day for skiing. Pouring outside? Who cares! “Hey, Harrisburg! It’s a great day for skiing!”

I set up shop that first day in the kitchen, into which Mark stumbled a few minutes after 6 a.m. How was I doing?, he asked. “Good!” What was I doing? “Why, the ski reports!” Well, Mark kindly informed me, he didn’t need to wake up for another three hours. Translation: I needed to find another location. And there was only one room available.

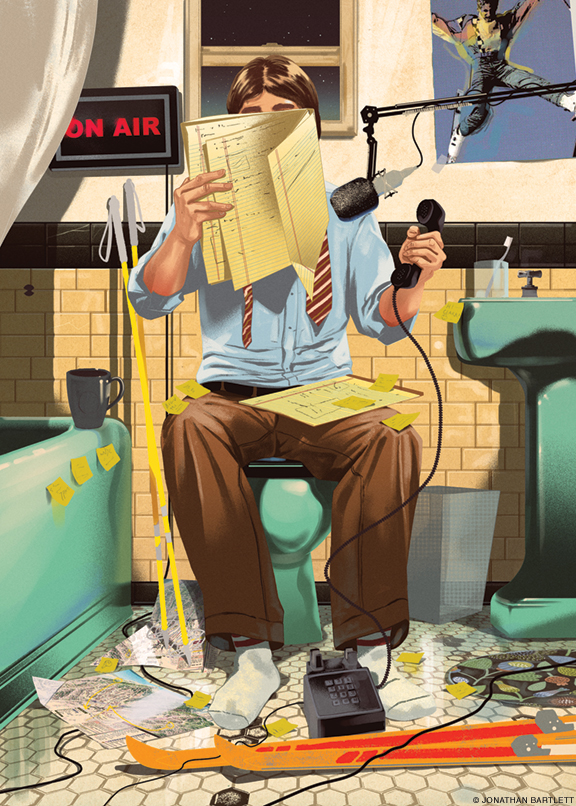

Which is how it came to pass that, during the winter of 1985–1986, I spent three hours every weekday morning reporting ski conditions from our bathroom. I sat on the toilet, with a tray table in front of me holding my notes and the apartment’s phone, at the end of its long cord. If it was 35 degrees outside, it might reach 45 inside. The paint peeled, the pipes hissed. Occasionally I would flush mid-report for a laugh. The hilarity had a way of wearing off, though, when between calls I asked myself how I’d ended up here.

Yet I was on the air, including four stations in New York (one of which was K-Rock, then the home of Howard Stern, who allegedly made fun of my name one day. At the time, it was a career highlight). People started to hear me. Occasionally friends of friends would call seeking my recommendation for a weekend of skiing. Should we go to Gore? Whiteface? Bromley? “I can’t even afford to go to one of these places for a single day,” I didn’t tell them. “And even if I could, I don’t know how to ski!” I opted to keep that to myself.

One day my contact at a Pittsburgh station asked me to change my name. From Mishkin? What, I wondered darkly, could possibly motivate that request? He even had an alternative name picked out: Eric Carter.

I was many things in this world, but I was not an Eric Carter. But what could a toilet-mounted ski reporter do? Thus began my brief Pittsburgh radio career as Eric Carter. The reason turned out to be benign: my reports were running on a competitor station, which made for a branding headache. The only problem was that occasionally I would forget, starting the ski report as Eric Carter and finishing it as Budd Mishkin. Such was the lot of the semi-professional broadcaster. Edward R. Murrow, I was not.

A single ray of hope flickered across the porcelain that winter. One of my stations was WNBC in New York, which then owned the radio rights to the Knicks and the Rangers. It was launching a five-hour talk show called Sportsnight, produced by a young man named Mike Breen—now known to sports fans as the voice of the NBA. For some reason, WNBC decided to include my ski report in the show’s first half-hour. So Mike and I talked most days when I called it in, and eventually I pitched his bosses on hiring me to cover New York baseball. After all, when the basketball and hockey seasons ended, Sportsnight would still have five hours to fill. Alas, their answer amounted to: Nice try, but no cigar.

And then ski season was over. The bathroom reverted to a bathroom, and as spring sprung I was unemployed. Again.

The next month, Budd Mishkin C’81 got a call from WNBC offering him the Yankees beat, which became a springboard to a long career in sports and news broadcasting. A couple years in, noticing a pile of audition tapes that had apparently been passed over in his favor, he asked Mike Breen why the job hadn’t gone to one of those hundreds of applicants. “We knew you from the ski reports,” the future voice of the NBA replied.

Brilliant! I spit out my coffee at this line:

“ A single ray of hope flickered across the porcelain that winter. ”