Class of ’87 | Rick Cohen C’87 came to Penn as a highly touted football player and left as little more than a four-year benchwarmer for the Quakers—or, as he put it, “one of 1,000 high-school All American players that get to play college football and wind up doing nothing.” The experience was a humbling one for Cohen, who, as a smart, popular high-school jock from Long Island, was used to things going his way. But it also proved instrumental in developing the kind of attitude necessary to discover his true ambition.

Later, through failed marriages, career changes, cross-country moves, parental disapproval, and a devastating car accident that very nearly smashed his dreams, Cohen did the same thing he had done during his Penn football days: he kept showing up. And now, with his past hardships serving mostly as a catalyst, Cohen has carved out the career that he always wanted: as a filmmaker specializing in sports documentaries that explore the human condition.

“What he’s been through, in my own humble opinion, would take down the strongest of people,” says Todd Feldman, a Hollywood producer and one of Cohen’s best friends in the entertainment business. “But even after all the stuff he’s been through, he just never lost his passion. And he certainly never lost his persistence.”

Cohen’s latest film, called Season of a Lifetime (seasonofalifetime.tv/), features a man who’s seen the darkest of days himself: a high-school football coach in Georgia named Jeremy Williams who suffers from amyotrophic lateral sclerorsis (ALS), also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease.

In the film, Cohen and his crew follow Williams throughout the 2010 high-school football season—his last as head coach of the Greenville Patriots in tiny Greenville, Georgia. Though Cohen caught some dramatic football moments during the Patriots’ quest for a state championship, the film is more about family, race, and religion than sports. Williams—a white, former star football player at what was then called Memphis State—uses his never-dying faith to rally his team of mostly poor, black players (many of whom say they view Williams as a father figure) and keep his family upbeat, even as his motor and verbal skills are deteriorating from the fatal disease.

In one particularly poignant scene, Williams puts his son—who suffers from spina bifida, and like his father, is in a wheelchair—to bed one night; in another, he tries to lift his son into their car. Perhaps that’s why Cohen became incensed when a camera guy loaned from ESPN turned to him after Greenville lost its first game of the season and said, “Well, I guess there goes your movie.”

“I literally threw the guy off the set because he obviously didn’t get the point of the movie,” Cohen says. “It obviously worked out amazing for us.”

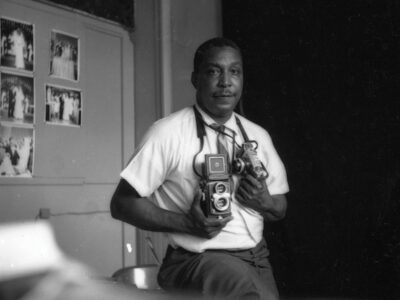

A couple of years earlier, Cohen made his debut documentary by similarly trying to humanize ex-athletes outside the field of play. This time, he had a little more knowledge about the inner workings of the film’s main character: himself.

Faded Glory, an ambitious project that he wrote, directed, produced, and starred in, documents Cohen’s own life as he tries to recreate some of his glory years by reuniting his old pals from a 1990s adult baseball team to compete in the 2007 National Amateur Baseball Association World Series. As with Season of a Lifetime, the results of the games weren’t nearly as significant as the examination of the players’ past problems, which include drug use, rocky marriages, and some serious injuries and illnesses.

Many of Cohen’s struggles were not only chronicled in Faded Glory but came about as a result of making the film—which took three years to complete before its 2009 release and, he says, cost him his second wife, his job, and his home.

But for Cohen, it was well worth it. And even though Faded Glory only reached a couple of theaters and never became a profitable venture, it was hailed by some critics, cheered at some film festivals and became, according to the director, something of a cult film for middle-aged ex-athletes.

“That was a passion project of his forever,” says Marc Sternberg, another producer, friend, and colleague of Cohen’s. “Against everybody’s advice, he went out and put this whole thing together while learning on the fly. The worst thing you can tell Richard is, ‘No, you can’t do it.’ Because he’ll figure out a way to do it.”

Cohen first became interested in the entertainment field while at Penn, where he performed in skits for the school’s television station, UTV, and decided to change his major to communications, leaving his pre-med classes behind. That switch produced one of many arguments he’s had with his father, Arnold, whom Cohen openly featured throughout Faded Glory as a stern man who harshly disapproved of many of his son’s decisions.

“When I told my dad I was going to switch to communications, he just about flipped the lid,” Cohen says.

After graduating from Penn, Cohen worked as a TV commercial actor in New York and sent a screenplay to a Hollywood agent. The agent’s positive response—following an earlier trip to LA with ex-football teammate Rich Comizio W’87, a star running back for the Quakers in the mid-’80s—stoked Cohen’s fire. And so, on New Year’s Day, 1991, he packed his belongings into his Ford Mustang and set off for the City of Angels.

He sold his first screenplay the following year. Soon after that, he was tasked to rewrite a couple more. He met an actress he planned to marry. Everything was going just as he had hoped. Then, the accident.

It was Kol Nidre (the evening before Yom Kippur) in 1994 when a truck driver hit the gas pedal instead of the brakes, plowed into Cohen’s Mustang, and dragged his car across US Highway 101. Cohen was able to get out of the car before it blew up, but he could not escape the brain trauma, 300-plus stitches, facial contusions, separated shoulder, and broken thumb caused by the crash. Eight months after the accident, he pulled a piece of glass out of the corner of his eye. While lying in his hospital bed, he remembers thinking four things: “There goes my good looks. There goes my acting career. There goes my writing career. My wife’s not going to marry me.”

Cohen still got married six weeks later but, as he predicted, the accident began to wreak havoc on his life. He suffered from headaches and had concentration lapses, which hurt his writing career. Instead, he went into business with his wife, running a teenage beauty pageant for the rest of the ’90s. But his marriage hit the rocks when he reluctantly agreed to move to Georgia in 2000 to be closer to his wife’s family. They got divorced shortly after the move because, in Cohen’s words, “I hadn’t wanted to leave my friends and my career, and she wanted to be a Stepford wife.”

Cohen remained in Georgia to stay near his two children, but never really got comfortable, holding a variety of jobs that ranged from bartender to teacher to coach to a position with a mobile marketing company. Finally he decided to return to his passion—filmmaking—even if it wound up costing him his second marriage.

“Up to the point of Faded Glory,” Cohen says, “I was always living my life to please other people. Finally I put an end to that.”

Of course, Cohen still doesn’t know how successful he’ll be as a filmmaker—besides Faded Glory and Season of a Lifetime, he has also directed a short documentary about football at a Christian school called And the Lord Said … Smack ’em in the Mouth—or where Season will land.

But no matter where it goes and how well it’s received, he’s pleased with the finished product—and with how far his passion and persistence have taken him.

“I was reintroduced recently to a quote by Mike Tyson, who said, ‘Everyone’s got a plan until you get punched in the face,’” says his friend Rich Comizio. “He’s been through so much adversity, but he’s been able to keep his mind on what he wanted to do. Come hell or high water, he was going to get to his passion—whether it was two years after graduation or 20.”

—Dave Zeitlin C’03