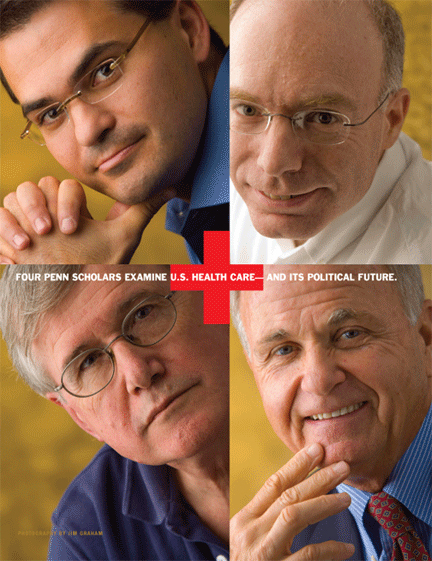

By Samuel Hughes | Photography by Jim Graham

Few things cause eyes to glaze over faster than discussions of health care. Unless, of course, your insurance rates just spiked, or you couldn’t get insurance, or you thought you were covered for a procedure but aren’t, or you’re trying to keep your company’s benefits competitive, or you’re just kind of appalled at the fact that there are more than 45 million Americans without any health insurance at all. With the 2008 presidential election campaign heating up—and in the wake of Michael Moore’s documentary Sicko—the business of health care is suddenly, if not a hot topic, one that can’t easily or responsibly be ignored.

To get some insights, we asked four Penn-based experts in the field for their thoughts on health-care matters: Dr. David Asch, executive director of the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics and the Eilers Professor of Health Care Management and Economics; Dr. Arnold Rosoff, professor of legal studies and health-care systems and a member of the medical school’s public-health program; Dr. Mark Pauly, professor of health-care systems, business and public policy, insurance and risk management, and economics; and Dr. David Grande GM’03, instructor of medicine. All four are senior fellows at the Leonard Davis Institute.

How would you summarize the current state of health care and health-care coverage in the U.S. today, both for those with insurance and those without?

Asch: It is pretty common to hear complaints about health care in the U.S. that remind us that we spend more on health care than any other country and achieve population health outcomes lower than other industrialized nations and, to boot, we leave 47 million of our citizens uninsured. But those sorry facts end up disguising the much more complicated reality, which is that what we really have is an extremely broad distribution of health-care costs and spending across segments of the population and an extremely broad distribution of health-care outcomes across the population. So, when someone asks me to characterize the state of health care in the U.S., I need to ask them, “Which U.S. are you asking about?” The averages tell you nothing in a country like ours.

Pauly: Medical-care spending growth has slowed substantially, but it’s still higher than GDP growth. The slowdown is largely due to a slowdown in drug spending growth, caused by older drugs going off patent, and the rate of introduction of new drugs has slowed a lot. So for those who can still afford insurance, the good news on spending and premium growth is mixed with bad news on beneficial but costly new technology.

The proportion of the population with no insurance is still growing, and has now exceeded its previous high-water mark in 1996. The story is quite different for those with insurance: Both the amount of insurance benefits and the proportion of spending paid by insurance is growing. The dollar amount of consumer cost-sharing has increased, but less rapidly than the dollar amount of insurance benefit payments. But the fraction of those without this better coverage is rising somewhat. The uninsured have very mixed characteristics, but the most typical uninsured person is a young lower-middle-class worker in reasonably good health employed at a small firm. Serious and costly efforts to broaden coverage like SCHIP [the State Children’s Health Insurance Program] and Medicare Part D are probably not going to have much of an effect on the overall measures of coverage or spending, though they help selected subpopulations. Moving toward universal (or even just much more) coverage will require dealing with insurance purchases for able-bodied adults.

Rosoff: Although there are more quality-control problems than there should be—i.e., medical error, as highlighted by the Institute of Medicine’s 2000 report “To Err is Human”—U.S. health care overall is quite good. In terms of technology and the educational/skill level of health-care providers, the U.S. ranks near the top of the world’s health-care systems. For Americans lucky enough to have good health insurance—a substantial portion of the population—U.S. health care is excellent.

There is, of course, a problem with rising cost, even for people with good insurance. This problem is increasingly felt by the general public because employers, who traditionally have borne the greatest burden of health-care costs, are increasingly shifting that burden onto their employees in various ways.

Michael Moore’s Sicko shines new light on old problems that are getting worse as time goes on. First, costs for health insurance continue to rise, pricing some—including small employers and their employees and dependents—out of the market. Second, too many people who have insurance find that when they need care, their insurance has limits and exclusions they didn’t know were there. Third, too many people simply don’t have insurance coverage.

The U.S. is the only major industrialized nation on the planet that has not committed itself to the ideal of universal health-care coverage (UHC). Despite Medicare for the elderly, Medicaid for the poor, SCHIP, and other state and federal health-care programs, roughly 47 million Americans—close to 1/6 of our population—still lack coverage. EMTALA (the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act of 1986) requires all hospitals participating in Medicare to assess, and treat if necessary, all who show up appearing to need emergency care; but that’s way too small a band-aid to cover up the gaping hole in coverage.

Sicko seems to have touched a nerve in this country. What is Moore right about and what is he wrong about? Are his depictions of the health-care systems of Canada, the U.K., France, and Cuba fair and balanced or is he looking through a rose-colored camera lens?

Asch: Here’s what Michael Moore got right: a sense of outrage. I think we need to congratulate him for so effectively communicating some serious problems within U.S. health care. Fixing those problems won’t be as easy as complaining about them. But complaining about them is important.

I’ll admit that Michael Moore is not the right person to ask to fix our health-care system. But neither is anyone asking any of us to make movies.

One of the common statements about the Canadian health system is that no matter how well it works, it would work a lot worse if Canada weren’t so close to the U.S. The proximity of the U.S. to Canada gives some options to impatient Canadians.

Pauly: Americans want insurance to pay for the care they want, when they want it, and from whom they want it. That does not happen in Canada, the U.K., or Cuba; I am not an expert on France. Generally access to primary care is better in those countries, but access to costly or high-tech care is rationed either by wait time or (in the case of Cuba) by political position. Some, perhaps many, Americans might prefer these kinds of systems, but surely not all.

Rosoff: Canada and the U.K. have well-documented problems of “rationing by the queue,” that is, long waits for elective and semi-elective treatments. (Some things that would be considered urgent care in the U.S. are classified as “elective” in Canada and the U.K.) Significant numbers of people in Canada go outside of their country’s universal health-care system and come to the U.S. as “medical tourists” to get care without the wait.

Although I have little first-hand knowledge, I tend to believe that the French health-care system is quite good, as the World Health Organization’s ranked France’s health-care system No. 1 in the world in 2000.

While I doubt Moore’s depiction of the Cuban health-care system as superior to our own and doubt that the average Cuban gets care anywhere near as good as the Americans that Moore took with him to Cuba, the WHO’s statistics show Cuba as having more than twice as many physicians per capita than the U.S. and 50 percent more hospital beds per capita, too. Still, WHO’s 2000 ranking listed Cuba 39th among the world’s health-care systems and the U.S. only slightly better, at 37th.

With the presidential election coming, is the time ripe for health-care reform? And is it a good idea?

Asch: I understand the important distinction between talking about health-care reform, however we define it, and actually getting the political traction to achieve it. But I believe that substantial health-care reform is possible. People used to say that the Veterans Health Administration couldn’t change, that it was too complex—too mired in the personal interests of bureaucrats, clinicians, beneficiaries, politicians, and industry—and that in that setting, the status quo was the safest political option. And while I don’t mean to suggest that VA health care is as complex as U.S. health care more generally, many of the same stakeholders and their interests exist in both settings. Over the last 20 years, the VA has transformed itself from a system people used to snicker at to one of the leading systems in quality and efficiency in the U.S. I certainly hope the next administration doesn’t decide health reform is too hard.

Grande: Strong presidential leadership is a must for health-care reform, so the election offers a great opportunity. The country appears to be ready for the next great debate on health care. During the [1993-94] Clinton debate, managed care was offered as a solution. It obviously didn’t work; the public sees this, and wants change. Beyond overcoming powerful interest groups, the biggest obstacle for reform is that most of the country has insurance and it is easy to stoke the public’s fear of change. That was the primary strategy of the “Harry and Louise” ads.

Pauly: The time is ripe to talk about something that could be labeled reform. Past history does not suggest unbridled optimism, however.

Is it a good idea? Depends on what kind of reform you have in mind and what you mean by “good.” Reducing the number of uninsured by paying substantially higher taxes (say, about $1,000 more per family per year) is what I personally would prefer to do, but I doubt there is a majority of taxpayers in favor of paying the $100 billion needed for this kind of reform. Some of the Democratic candidates have come out in favor of spending the kind of real money needed, but others would rather talk about “improving efficiency” first. Republicans tend to favor smaller-scale incremental reforms.

I personally am dubious that the kinds of resources needed to pay for the care that the uninsured currently go without can be raised by reducing waste, fraud, and abuse. I fear there is not enough inefficiency that we know how to stop to pay the high price tag for providing real insurance to substantial numbers of the uninsured.

Rosoff: In order to have major reform in any context, the parties in interest have to agree on a solution. That’s difficult enough, but if they don’t even agree on what the problem is, gaining consensus on the solution is well-nigh impossible. That’s the situation with U.S. health care.

A large proportion of Americans have insurance and are concerned that it’s too expensive, getting more expensive, and has too many coverage limits. Then there are the more unfortunate ones, some 47 million, who don’t have insurance; for them the problem, while still a cost problem, is fundamentally different. Sadly, the solution for the first group is likely to disadvantage the second group, and vice versa.

A move to a government-run system, either a single-payer system or some form of managed competition, might help both groups; but it would be such a reversal of our long-standing beliefs and practices favoring private-sector mechanisms over governmental control that it’s not likely to be politically achievable. The Clintons ran into that buzz-saw in 1993-94!

The U.S. spends a very high percentage of its GDP on health care, and a good deal goes to administrative costs and returns to private health-insurance shareholders. Why is our variegated private system a good thing? Are we getting our money’s worth out of it?

Asch: Just because people in our diverse nation make varied choices doesn’t mean that these choices are good ones. It isn’t just that choice costs money. It’s also that when it comes to health care, people often make poor choices. That is true of physicians and patients and health-care managers. For example, there are some obvious forces that encourage the use of expensive technologies when cheaper ones are better.

Pauly: This is an important and popular error. The main reason for high spending in the U.S. relative to other countries is because we provide higher incomes to doctors, hospitals, and drug-company stockholders than they do. Administrative costs would be reduced in the U.S. if private insurance was mandated, since the largest share of administrative costs goes to pay for selling insurance and for collecting premiums. There may be some scope for reducing administrative costs through better information technology, but large private insurance groups can achieve about the same administrative cost as public Medicaid.

Why is our variegated private system a good thing? Because we do not all want the same thing. Eighty-plus percent of Medicare people buy a plan that is different from the basic uniform government-run plan, either by adding Medigap, going on Medicaid, or using private plans. And this variation occurs even though the people choosing the plans are not paying for them. The variation across plans and the voluntary [nature] of coverage for people under 65 are the reasons for somewhat higher administrative costs. In health care as in dining, ordering a la carte costs more. If income were distributed more evenly and people were more similar in terms of preferences for risk, lifestyle, and waiting on line (say, if we were more like the Swedes), there would be much less of a case for offering choices through a private system.

I do not favor the current uneven distribution of income in the U.S., but the population generally seems to accept it. Given wide and acceptable variations in income, we will not be getting our money’s worth by having either a uniformly lavish or uniformly stingy plan for all.

Are we getting our money’s worth out of it? We are certainly better off than we would be if we spent less on health care or health insurance and did not change anything else. Research shows that the growth in spending has, in the aggregate, been “worth it,” with conservative estimates of the money values of benefits from the new technology that spending goes for being four to seven times the value of their cost. But the uninsured are left out of this, and even lower-income people with insurance may not value the benefits so highly, relative to other ways they could have used their incomes.

As with many other things, in theory we could get more for less. But although many claim to know the amount of inefficiency in the system, I do not know anyone who knows a good way to reduce it.

I do think that, if any institutional structure will offer incentives for greater efficiency, it would be some type of competitive market—differing, in my view, from current insurance markets by having lower subsidies to upper-middle-income families like mine and better information for people when they choose insurance.

Rosoff: I think we went down the wrong road conceiving health care as a consumer service in a market-based free-enterprise system. And I say that despite having been a proponent for years of market-based, competitive, managed- care models. I believed—as did many others, and as many (mostly Republicans) continue to believe—that competition is the key to achieving quality care at reasonable cost.

Competition is great in some applications, but there are important reasons why competition among health plans will not deliver to Americans the benefits traditionally claimed for market-based systems. Effective competition requires choice among alternatives. Choice costs money. Unless the public has the ability, will, and energy to use its latitude of choice wisely and well, it is money thrown away.

I think the prescription for health-care reform in this country should focus on choice of providers rather than choice of health-care plans. That is essentially the Medicare model. Whether we can achieve that for the mass of our population is an open question.

President Bush was recently quoted as saying that “people have access to health care in America. After all, you just go to an emergency room.” Is this a realistic response?

Asch: To me, the bigger problem with this response isn’t that President Bush said it, but that lots of people believe it. Everyone understands that when Scrooge asks, “Are there no prisons? Are there no workhouses?” he is missing the point about what constitutes adequate care for the poor. But if lots of people think emergency rooms have solved our uninsurance problem, then they need to spend some time with Tiny Tim.

Grande: The only health care Americans are guaranteed access to is emergency rooms. EMTALA is the only law that gives Americans a right to some health care—but only for assessment and stabilization. To consider this a minimum standard for decent health care in the richest nation in the world is ridiculous. It neglects the importance of primary care and prevention and the proper management of chronic illnesses that improve the chances of living a healthy life.

Pauly: Depends on whether he meant “some health care” or “the right amount and type of health care.” He is right under the first meaning; federal law requires ER patients to be treated and stabilized. He is wrong on the second, but the administration is aware that using the ER as a port of entry into the system is not the best way to do things. Seems like you are trying to follow Moore in finding “gotcha” statements.

Rosoff: I agree with David Grande on this. Even assuming hospitals’ “dumping” of sick people in violation of EMTALA—as depicted so poignantly in Sicko—is an aberration, adequate health care is way more than just episodic emergency treatment when one is in an extreme state. In most cases it costs more to deal with an illness when it has progressed to an “emergency room” state, and the outcome of the treatment is likely to be worse. To the extent that we use emergency rooms as de factoprimary care centers for the uninsured who are not in extremis, that is an extremely costly way to take care of lesser ills.

What are the worst ideas by the presidential candidates, and the most cowardly evasions?

Asch: The concept of choice has been co-opted and is now just code for market-based approaches. Choice in selecting an insurance plan is mostly about structuring financial risk. Choice in more clinical health-care decisions might seem like a more important issue, but its value is substantially over-rated. Sure, we may differ in our preferences for bedside manner, or for more aggressive medical and surgical approaches. But most of us share the same overall goals: to live longer and with less disability.

In fact, the prevailing approach to improving health-care quality has concentrated on the standardization of care, not the proliferation of options. Choice isn’t what’s missing in health care. It’s disingenuous at best to suggest that preserving choice needs to be an important priority compared to reducing waste, improving quality, and achieving universal coverage.

Pauly: Any proposal to do something about the uninsured is better than what we have. Progress on this matter has been stymied because advocates will only support their best plan and therefore block other reasonably good plans—because this is the irrational way politics works.

Probably the worst idea is to propose employer mandates, because the cost of those mandates will surely fall almost entirely on (future) worker wages, not capitalist profits. Yet many employers, confusedly thinking it is their money that goes to pay worker health-insurance premiums, succeed in stopping any serious attempt to reduce the number of uninsured adults.

John Edwards’ proposal would require businesses and other employers to either cover their employees or help finance their health insurance, yet he also says that businesses and other employers “will find it cheaper and easier to insure their workers.” Is this plausible?

Pauly: An employer currently not paying workers in the form of health insurance might find insurance cheaper under Edwards’ plan, but it will still cost a lot. Why vote for someone who will lower the cost of something you do not want to buy? Of course, employers are all confused because they think the cost of coverage will come out of their profits, when in fact it will come out of their workers’ future raises. I do not know why we insured workers should favor proposals that will reduce the wages of currently uninsured workers; as I said before, I would prefer to finance insurance subsidies targeted to lower-income families by broad-based income taxes.

Rosoff: I think it is plausible. You have to take each statement in its appropriate context. If you do they can both be right, but they can’t both apply to all employers across the board. For example, if you have a small employer who now doesn’t attempt to provide health insurance for its workers because it’s too expensive, it’s not going to be “cheaper” for that employer to now start covering the workers. However, if you structure new insurance pools so that small employers can get health-insurance rates approximating those for large employer groups, those employers will find it “easier and cheaper” to insure their workers than they otherwise would.

Fred Thompson said recently that “the poorest Americans are getting far better service” than Canadians or the Brits. True or false?

Asch: False.

Pauly: They probably are if they are really sick and get to a good hospital; they probably aren’t if they are reasonably well and seeking preventive or routine care.

Mitt Romney, who would “like to see every state do their best to get everybody insured” by private insurers, says that a Democratic health-care plan would result in “socialized medicine,” and that if we go down that road, we’ll end up with the “consequences of Europe,” including a stagnant economy and higher unemployment. Please comment.

Asch: When was the last time you bought some Euros with U.S. dollars? It’s not pretty.

Pauly: It is true that if we would shift the $800 billion of now-private spending to the government and pay for it by adding it onto a progressive tax structure, there would be a large jump in tax-induced distortions and waste for the economy as a whole. The Germans are moving in our direction by lowering the tax-financed part and the French may well go that way under Sarkozy.

Hillary Clinton’s health-care proposal, which started out as an “agenda to lower health-care costs and improve value for all Americans,” has evolved into a pretty specific plan. How feasible is it?

Asch: Senator Clinton’s plans have become increasingly more specific since the summer. She has emphasized the goals of universal coverage, portability, affordability, choice. She wants to use the Federal Employee Health Benefit Program as a model—something many have urged for years. She says she will lower costs through modernization and an emphasis on prevention—good things, of course, but not ones that seem likely to lower costs. I think there may be huge gains from eliminating waste, but I just don’t think we’re at the point on the curve where higher quality is going to lower costs. The financial support for her plan might come from rolling back Bush tax cuts and making the employer health-care tax-deduction less generous, certainly for those with higher incomes.

No specific plan is going to survive an election intact anyway. The important and potentially enduring distinctions among candidates are at the level of principle, not detail: How much is government and how much is free market? Is universal coverage a priority, or just a hope? And finally, is it really change, or is it just business as usual?

Rosoff: As the Harry and Louise ads showed, people in the U.S. who have health-care insurance will resist change if they fear it will make their situation worse. Their fear: If the current system is already plagued with cost and quality problems, how much worse might those problems be if we stretch the system to include another 45-plus million people. In other words, the “haves” don’t want to be worse off as a result of doing what, in the abstract, they would agree should be done to make the “have-nots” better off.

Some would say that shows selfishness and a lack of cultural solidarity among the American populace. Perhaps they are right. Those nations that have gone down the path to universal health care have displayed a culture of solidarity well beyond that which the U.S. has demonstrated. As a people, are we capable of rising to that level of solidarity? That is a key question. Clearly it would take a strong leader, a persuasive champion, to awaken that sense of shared destiny in us.