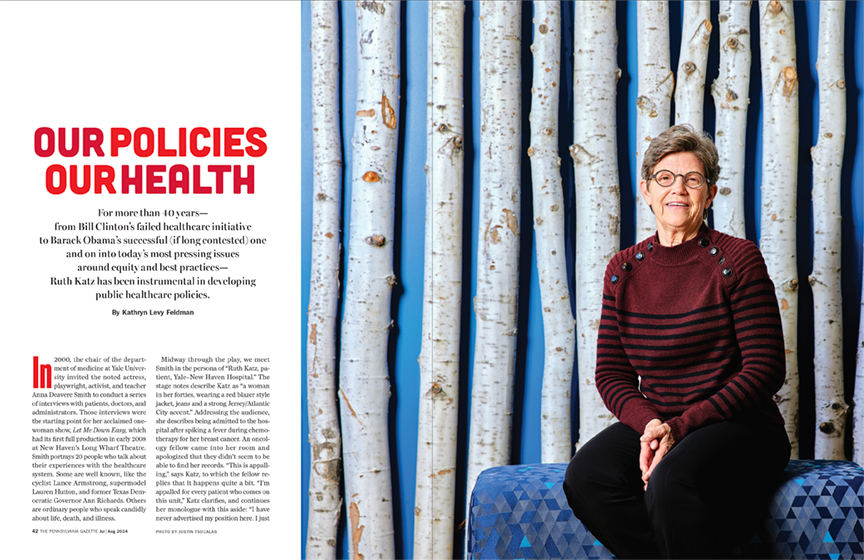

For more than 40 years—from Bill Clinton’s failed healthcare initiative to Barack Obama’s successful (if long contested) one and on into today’s most pressing issues around equity and best practices—Ruth Katz CW’74 has been instrumental in developing public healthcare policies.

By Kathryn Levy Feldman | Photo by Justin Tsucalas

Download a PDF of this article

In 2000, the chair of the department of medicine at Yale University invited the noted actress, playwright, activist, and teacher Anna Deavere Smith to conduct a series of interviews with patients, doctors, and administrators. Those interviews were the starting point for her acclaimed one-woman show, Let Me Down Easy, which had its first full production in early 2008 at New Haven’s Long Wharf Theatre. Smith portrays 20 people who talk about their experiences with the healthcare system. Some are well known, like the cyclist Lance Armstrong, supermodel Lauren Hutton, and former Texas Democratic Governor Ann Richards. Others are ordinary people who speak candidly about life, death, and illness.

Midway through the play, we meet Smith in the persona of “Ruth Katz, patient, Yale–New Haven Hospital.” The stage notes describe Katz as “a woman in her forties, wearing a red blazer style jacket, jeans and a strong Jersey/Atlantic City accent.” Addressing the audience, she describes being admitted to the hospital after spiking a fever during chemotherapy for her breast cancer. An oncology fellow came into her room and apologized that they didn’t seem to be able to find her records. “This is appalling,” says Katz, to which the fellow replies that it happens quite a bit. “I’m appalled for every patient who comes on this unit,” Katz clarifies, and continues her monologue with this aside: “I have never advertised my position here. I just want to be treated like everyone else.” The doctor goes on to ask Katz whether she works. “I do,” she replies. “Are you working full time?” asks the doctor. “I am,” says Katz. “Where are you working?” the doctor inquires. “I’m associate dean at the medical school,” says Katz. “At this medical school?” he wonders, now looking up from his notes. “At the Yale School of Medicine,” she replies, adding to the audience: “They found my files within a half hour.”

The line draws a laugh, but to Katz CW’74 it’s nothing to joke about.

Long before becoming a patient herself, she had devoted her career to researching and developing healthcare policies that challenge the inequities of the system. “My client has been the public,” she says.

Currently a vice president and executive director of the Aspen Institute’s Health, Medicine & Society Program, and director of Aspen Ideas: Health, Katz has previously worked on multiple Congressional committees under Democratic US Representative Henry Waxman of California on healthcare initiatives during both the Clinton and Obama administrations. Her resume also includes a stint at the Kaiser Family Foundation; a failed run for Congress vying to represent her hometown of Ventnor City, New Jersey; and serving as dean of the Milken Institute School of Public Health at George Washington University as well as associate dean of Yale’s medical school.

“I’ve been involved in health and healthcare in a lot of different ways, always through the lens of policy,” Katz says. “But what’s been extraordinary for me and very exciting has been [being] able to do it from different perspectives, whether at a medical school or a school of public health or on Capitol Hill or at a foundation.”

Katz traces her early interest in health to her relationship with her cousin, Michael Katz, a cardiologist who practiced in both Ventnor and Philadelphia. “I used to go to HUP with him during my last year at Penn when he was practicing there,” she recalls. Her interest grew during law school at Emory University, from which she graduated in 1977. “During law school, I really came to appreciate the role of the law and people’s access to healthcare, the business of healthcare, and the regulation of healthcare,” she says. “It’s a fundamental part of how our healthcare system works.”

In fact, Katz was so focused on health law that when the professor at Emory who taught those courses went on leave during her third year of law school, she managed to transfer to Penn Law as a special student so she could take those courses. “I didn’t graduate from the law school,” she says with a laugh, “but I spent my last year there.”

Katz went on to a job at the Philadelphia firm then known as Dilworth Paxson Kalish and Levy, where she was assigned to what was at the time the largest lawsuit ever tried in Pennsylvania state court. She spent nine months commuting between Philadelphia and Pittsburgh on the case—more than long enough to conclude that “this kind of law was not for me,” she says.

After finishing the case, she applied and was accepted to the Harvard School of Public Health. Her request for a leave of absence to attend was unusual at a moment when women had just begun entering big law firms and being considered for partnerships. “I know they all thought I was nuts,” Katz says. But they granted her the leave.

Katz graduated from Harvard in 1980 and never returned to the private sector—although the managing partner of the firm offered to hire her to run its burgeoning health law practice in 1994, after Katz lost her staff position on Capitol Hill when Republicans took the House. “Obviously I didn’t go back to practice law, because I’d been involved in policy” during those intervening years, she says. “But I never thought that health law would become its own specialty, and it has.”

Katz’s first job in Washington was a one-year position as counsel for the Select Panel for the Promotion of Child Health, which she took on to test whether “Washington and health policy [was] really the right thing” for her and discovered “it really was.” From there she served as a legislative aide in the House and then as counsel for what was then called the Subcommittee on Health and the Environment, one of the subcommittees of the Committee on Energy and Commerce, which Waxman chaired. “I was with the subcommittee until we all lost our jobs in 1994 when the Republicans took back the House,” she says, and then went back to work for Waxman in 2009, when he lured her away from her deanship at George Washington University’s School of Public Health. “Henry recruited all the old-timers back to work on what would become Obamacare,” she says. “And virtually all of us [who had worked on the Clinton Health Reform package that failed in 1992] went back.”

Waxman describes Katz as “determined, competent, and so good at communicating.” One of her responsibilities was to count the votes among the Democrats both at the subcommittee and full committee level when legislation was being considered. When amendments were offered, she clarified them for the Democrats. But even some of the Republicans trusted her to give them “an honest lay of the land,” Katz says. “This is an example of the old-school days when so much of Congress ran on trust. It’s not working now because people don’t trust each other.”

During her first stint in the House, Katz spearheaded an effort to make nursing home reform one of Waxman’s major initiatives. In 1986, the National Academy of Medicine had put out a major report on nursing homes detailing what Katz calls “a major breakdown in what was happening with care.” Katz and another staffer spent the better part of a year working on what would become the Nursing Home Reform Act, signed in 1987, which was the last major revision of federal regulations for running and staffing nursing homes and reimbursing care under Medicare and Medicaid.

A strong proponent of women’s health, Katz also worked on the National Institutes of Health Reauthorization Act of 1993, which among other things required that women, in appropriate numbers, be included in federally funded clinical trials. It also included a provision for fetal tissue research, an issue that Katz had worked on since Ronald Reagan was president. Reagan banned this research because of the perceived ties to abortion. There were fears that women would get pregnant and abort to potentially save loved ones with genetic illnesses that could be treated with a fetal tissue transplant. Nonetheless, Reagan had set up an executive committee to study the question. “Lo and behold,” Katz recounts, “the committee voted in favor of allowing the research to go forward with some ethical guidelines in place.” Nevertheless, in 1989, then President George H. W. Bush extended the ban indefinitely. Limited private research continued and many researchers in the field confined their work to animals.

An attempt to overturn the ban in 1990 never made it to the House floor, but the following year they got much closer to passage—thanks in large part to the Reverend Guy Walden, a fervently pro-life evangelical pastor from Houston, Texas, and his wife Terri, who Katz had “found by accident” in the interim. Their testimony before the House and Senate in 1991 “changed the whole debate,” Katz says.

At the time, Terri Walden was pregnant with a child who had been diagnosed with Hurler’s syndrome, a genetic disease that had already killed two of the couple’s children. Despite their religious stance against abortion, the Waldens had decided Terri would undergo an in-utero fetal tissue transplant with their current pregnancy, the results of which seemed promising at the time of their testimony.

“The researchers have shared with us that they believe the same technique could be used to ameliorate between 100 and 150 inborn diseases. Imagine the fetal lives that we could save with this research,” Walden testified. “We believe that saving the ones we can is the most pro-life thing we can do. Doctors who have the knowledge and the ability are being held back from fighting disease.”

The bill passed in both the House and the Senate but was vetoed by President Bush. An attempt to overturn the veto was successful in the Senate, with 97 yeas, well above the required two-thirds vote, but “we came up short in the House,” Katz recalls. Following the election of Democrat Bill Clinton in 1992, a new bill was introduced in January 1993 and passed. “I have the picture on my wall of me with Clinton, Henry, and two other staffers in the Oval Office the day the president signed it into law, less than six months after he took office.”

In between her stints on Capitol Hill, Katz first spent a year as director of public health programs at the Kaiser Family Foundation (now KFF). There she “gave out a lot of grants, so I made a lot of people happy,” she jokes. “But mostly, I worked on the work I continue to this day—women’s health.” She left the job in 1996 to run for Congress in New Jersey, where she had remained a resident while working in Washington, ultimately losing to the incumbent, Republican Frank LoBiondo, who would hold the seat until his retirement in 2019.

It was a tough race in which LoBiondo, according to the Atlantic City Press, portrayed Katz as a carpetbagger “out of touch with her South Jersey roots.” Katz in turn called LoBiondo “a gun-toting, tree-killing, Medicare-slashing, Newt Gingrich puppet, who voted to curb Medicare spending, cap federal student loan spending, and expand the conditions under which corporations can tap employee pension funds.”

“I thought I could do a better job representing the interests of the people of South Jersey,” Katz says, and 1996 seemed like the right time to take her shot, but “running for office was never a life-long dream” for her. “From the beginning, I said that if I didn’t win, I had another life. I enjoyed the work that I was doing, and I was fully prepared to go back and do it.”

After the election, Katz was contacted by David Kessler, the former commissioner of the FDA who had just been appointed dean of Yale University’s medical school. “The first call I made was to Ruth,” he recalls. Kessler asked her if she was interested in the position of associate dean for administration. “It was completely out of the blue, and I thought he was kidding,” she says.

She decided to take on the job and make her first foray into the academic world because it offered her the opportunity to be involved with healthcare from a completely different perspective and, she reflected, the chance to be the righthand person to the dean of the Yale School of Medicine might never happen again. But she had her doubts—chiefly, that she wasn’t “one of them.” Lacking an MD or PhD, Katz worried that she wouldn’t have credibility.

As it turned out, that “outsider” position was an advantage. “When I made a decision, people might not have agreed with it or they might not have liked it, but I don’t think anyone ever thought I made that decision because I was trying to advance myself at Yale. When I came to Yale, I came at the highest level I was ever going to go,” she says. “I could certainly speak their language, but I was never going to take any of their jobs. It was a really good lesson. Sometimes the thing you think may be your biggest deficit turns out to be your biggest asset.”

According to Kessler, he and Katz “did everything together. There are a thousand behind-the-scenes issues that make a medical school in a university run, and she was involved in all of that,” he says. “She played a major leadership role in every major initiative, recruited dozens of chairs, built hundreds of millions of dollars of buildings, forged the major affiliation agreements between the medical school and the hospital,” he continues. “And whenever there was a problem, the first office I would walk into, which was right next to mine, was Ruth’s.”

Kessler also remarks on Katz’s relationship with the students. “She is a true mentor. There was an emphasis, obviously, on great medicine, but also public service,” he says. “It is no coincidence that Vivek Murthy, our current surgeon general, and Mandy Cohen, current director of the CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention], were both students when we were deans there.” Katz notes that, during Murthy’s second year of medical school, he was one of the students who “won” a trip to Washington to meet with Henry Waxman, which she had contributed to their auction.

As a testament to the students’ respect and admiration for Katz, they chose her as graduation speaker in 2001, the year after she was diagnosed with breast cancer. “I remember one night when I was in the hospital, a bunch of third-year students were doing clinical rotations and were assigned to my care,” she recalls. “They were nervous wrecks. And I said, ‘You get in here. This is practice, and someday you’re going to have patients who you know. So practice on me.’ And one kid stayed with me the entire night. It was really amazing.” For Katz, the honor “was one of the greatest I ever had at Yale.”

When Katz moved on from Yale to George Washington University in 2003, the School of Public Health, established only in 1997, still “didn’t have our own building,” she says. Initially, Katz focused on finding top talent. “We recruited new deans for faculty affairs and new deans for student affairs and we revised the budget process,” she recounts. “Basically, we took a school that was still in its infancy in many ways, and really laid the groundwork to help build what is considered to be one of the best schools of public health in the country now.”

In 2009, Katz returned to Capitol Hill to work with Waxman on the passage of the Affordable Care Act (aka Obamacare) and stayed on for Obama’s first term. “I made it clear that I would leave once the legislation became law to pursue other opportunities,” Katz says. Exactly four years later, she joined the Aspen Institute as executive director of its Health, Medicine & Society Program, where she remains. For Katz, the opportunity to design a program with a focus on public health policy and educate the public about its importance was appealing. So was the variety of the work, since the position allowed her to focus on several aspects of public health, while remaining in Washington, where so much health policy is developed.

During her 10 years at the Aspen Institute, the Health, Medicine & Society program has done policy work on issues including vaccines, gun violence, maternal mortality, antibiotic resistance, end-of-life care, healthcare costs, and the arts and health. Katz also manages the annual conference Aspen Ideas: Health, a three-day forum, open to the public, that brings together policymakers, healthcare practitioners, community leaders, visionaries, scientists, and activists for stimulating, provocative, and challenging exchanges organized around themes.

Katz also developed and shepherds the Aspen Health Strategy Group, a task force that promotes improvements in health policy and practice whose membership ranges from political heavy hitters like former Secretary of Health and Human Services Kathleen Sebelius and onetime Senate majority leader Bill Frist to leading experts like Antonia M. Villarruel GNu’82, Penn’s Margaret Bond Simon Dean of Nursing. Each year, the group tackles a single health issue; its findings and recommendations are widely anticipated and disseminated by influencers and policymakers. Recent topics have included the opioid crisis; vaccine hesitancy; maternal mortality; health data privacy; gun violence; and (cochaired by the singer and performer Renee Fleming) on neuro-arts, or the positive impact of the arts on health and well-being.

Public health is in the national spotlight more than ever in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, Katz says. “I think people came to really understand that public health is about the health of populations; medicine or medical care is about the health of individuals.” At the same time, she adds, the pandemic showed the weaknesses in both systems. “I think we still have a long way to go to ensure that everyone in this country has access to good quality healthcare. We have to restore trust in the healthcare system. It’s not just healthcare—in democracy; in education; in leadership in our country,” she says. “And we still have a long way to go to ensure that we can help prevent the next pandemic—because it is going to happen. Nobody knows when. Nobody knows what it will be. Nobody knows how it will happen, but as we learned in public health school, it will happen. And we need to be prepared.”

Kathryn Levy Feldman LPS’09 is a frequent contributor to the Gazette.