An alumna is working to help kids—and parents—understand the media’s messages.

It took a while for Erin McNeill C’88 to notice all the ways that various media were snaking into her young sons’ brains. The time a Victoria’s Secret ad splashed across the TV while her two boys were watching a baseball game. When they tuned in to cheer on the Patriots and saw a commercial with a teenager getting shot. The cartoons that teemed with gender stereotypes. The Baby Einstein hoopla. The print ads touting violent toys for boys and pink Legos for girls.

As she clocked their subtle and not-so-subtle messages, she worried about how those messages might affect her kids as they grew up.

“I knew there was a problem,” McNeill would later write. “Commercial media was taking away our right and our privilege—as a society and as individual parents—to form and shape our young people.”

Now she’s working to return that power to parents, teachers, and kids themselves by championing “media literacy” legislation for schools.

It isn’t a term most people are familiar with, and it’s one that McNeill herself has trouble distilling. Eventually she settles on this: “Media literacy is about understanding the messages that we see and consume.”

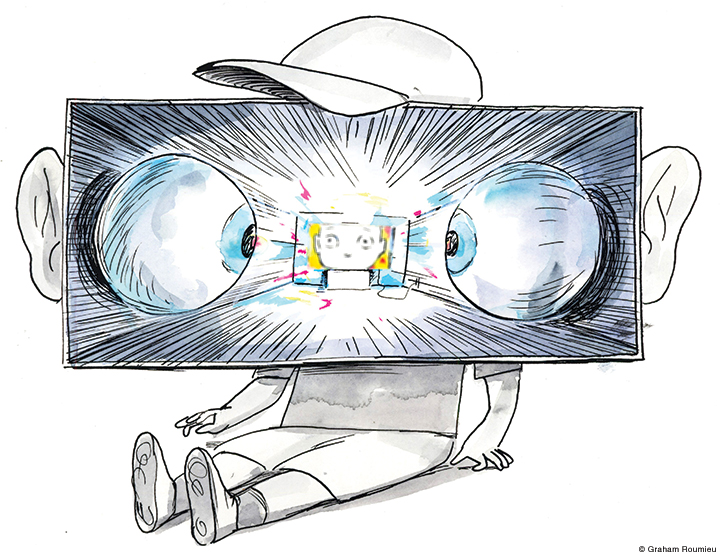

Those messages are everywhere—phones, tablets, laptops, magazines, TVs. They masquerade as ads, YouTube links, social media posts—even news reports. They skew the way kids see everything, McNeill says, from gender roles and career options to violence and sex.

In 2013, McNeill founded Media Literacy Now, which bills itself as “the leading national advocacy organization for media literacy education policy.” It’s already helped push several pieces of legislation forward, including a New Jersey bill to prioritize media literacy in state school districts and a Washington law that will help that state’s teachers implement media literacy education in every school.

While we could all use media literacy lessons, McNeill says, schools were the easiest access point. “It’s a place where you can write up a bill that legislators can pass,” she explains. “They can’t really pass a law saying that all adults need to attend classes.”

Media literacy education can take many forms. Kindergartners might learn that everything they see on their screens was created by someone else—that it has an author. “You may not say it that way,” she says, “but you can help them understand that when they’re watching cartoons, a person made decisions about what they’re seeing, and they don’t necessarily have to accept them or agree with them.”

By third or fourth grade, kids can start to learn about bias, sexism, and racism in media. In fifth grade, they can talk about how to use social media in a safe and ethical way.

“I’ve taken to saying media literacy is literacy in the 21st century,” McNeill says. “At one time, reading and writing was enough to be literate. Now it’s not.”

Becoming a policy crusader was never on her to-do list. “I think [old friends] might be surprised that I’m doing this,” she says. “I’m surprised myself, so why wouldn’t they be?”

After graduating from Penn as a history major, McNeill worked as a reporter and communications consultant for almost 30 years, including a recent stint writing and editing for the Washington-based Congressional Quarterly. But the more she thought about the media’s influence on her kids, the less she could ignore it.

“Every day I would recognize more types of media, more types of messages, and more ways that this affects everyone,” she says.

She began jotting down her thoughts in 2010, forming them into blog posts on a site she named Marketing, Media & Childhood. The blog led her to a realization: it’s almost impossible to change what the media are serving up to kids, so maybe the better response is to make kids aware of what they’re being served.

She began talking to teachers, who said that they had little pedagogical space to teach media literacy outside the mandatory curriculum. “I realized we needed to go to the policymakers, to make media literacy a priority in schools, which would give teachers the room to teach it and shift curriculum development resources and teacher training toward media literacy,” McNeill later wrote. “We needed to put media literacy on the agenda.”

She started Media Literacy Now as a national organization that could “help passionate activists in every state get a running start,” she wrote. By the end of its first year, the nonprofit was championing bills in Massachusetts (where McNeill lives), New York, and New Jersey. Today it has worked with advocates in more than 20 states.

For the first few years, McNeill struggled to make people care about her message, but following “the big ‘fake news’ crisis just before the [2016] election, I think politicians and journalists were suddenly awakened to how important media literacy is,” she says. “That’s when we started getting a lot more calls.”

While phony news stories, cyberbullying, body image issues, and the revelations of Facebook selling personal data may seem like separate issues, media literacy can serve as a common remedy. “The challenge for us is explaining how media literacy is a big part of the solution,” she says. “It sounds grandiose to say we’re trying to save the world, but I think it’s a part.”

She likes to think that her sons, now 19 and 22, are proud of the work that their childhood TV-watching helped spark.

“I seek advice from them all the time and it’s made for a lot of really interesting conversations,” McNeill says. And there’s this: Her younger son recently deleted all the social media apps from his phone—and, she notes, “he didn’t even tell me about it.”

—Molly Petrilla C’06

One important question students learn to ask when learning the critical thinking skills of media literacy is “What was left out of this message?” At only 900 some words, the article necessarily left out large parts of the story. Dan Sullivan has made a number of assumptions here, such as that the first step was to go to state government or that the result of legislative efforts will be centralized control of public education.

In fact, our advocacy work involves a great deal of grassroots coalition building and policymaker education over many years. Many of our advocates on the ground are teachers and students. Meanwhile, many people have worked for decades to develop and disseminate media literacy curriculum.

Many teachers are already teaching this way, but need help. As we have done our research and listened to teachers, school administrators, parents, students, social workers, legislators, media producers, curriculum creators, and other media literacy advocates, we have learned what teachers and schools need to support them in this work.

I invite anyone who wants to learn more about media literacy and what we are doing to advance this essential life skill for students, to go to our website, MediaLiteracyNow.org explore, and then get in touch with me with any further questions.

I don’t know why the first step is to run to the state government and impose legislation. How about selling the idea to some school teachers to see how it works? This suggests that Erin McNeill has her own biases to deal with and doesn’t trust the intelligence of students, teachers and school boards to do the right thing.

The more we have centralized control of public education, the worse that education has become. Let’s leave teaching to the teachers and try reasoning with them instead of going over their heads to legislators who don’t know nearly as much about teaching as the teachers know.