Improving patient care with the elements of design.

Emergency room physician Bon Ku C’95 can pinpoint the moment he realized that there was a lot more that he and other doctors could do besides stitch up patients and dispense medicine.

“There was a guy who I grew really curious about,” he recalls. “He was a ‘super-utilizer,’ someone who comes into the ER 200 or more times a year. I used to wonder what brought him in: Was he a drug abuser? Did he have no family? So I decided to visit him at his home in South Philadelphia, and it turned out that he was frightened of being alone and just felt safe at the hospital.” The man died of renal disease a few years after their encounter.

The experience had a profound impact on Ku. “It’s easy for us to label patients as ‘frequent-fliers’ or ‘drug-seeking,’” he says, “but hearing him speak about his family in his living room, and meeting his aunt, humanized him.”

Though he didn’t realize it at the time, Ku was “already practicing certain elements of design thinking,” he says. “At its core, it’s all about empathy, because it’s impossible to design effective solutions without understanding the needs of the users you are trying to design for.”

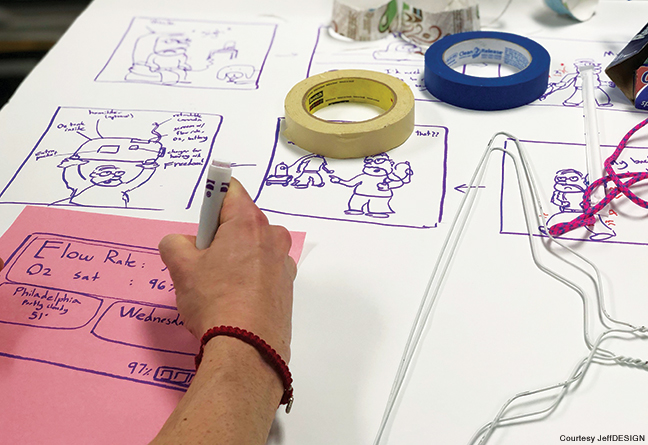

That’s why Ku, the assistant dean for health and design and an associate professor at the Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University, now serves as the director of JeffDESIGN, which he co-founded in 2014. The first such program within a medical school, it encourages doctors-to-be to develop a problem-solving approach by using techniques more typically associated with the design of smart phones or cars. These include identifying sticking points or obstacles, relying on play and experimentation, and arriving at solutions through rapid “low-fi” prototyping (cardboard and duct tape show up a lot).

“Almost everything in healthcare has a design component,” Ku says. He’s become an ambassador for the idea, speaking across the country and delivering TEDx talks like “Using Design Thinking to Create the Doctor of the Future” and “Why Doctors Need to Think Like Designers.”

This year, 80 students are enrolled in the program, working in a sprawling studio located in the Old Federal Reserve Bank Building (a huge walk-in vault sits at the center of the space). Ku usually invites architects and industrial designers to make appearances during class, and shelves are crammed with mock-ups of products that they’ve helped take from ideation to realization. One product, ALAFLEX, is an ergonomic under-arm bandage modeled on the layered structure of sanitary napkins to offer leak and odor protection for patients with a chronic skin condition called hidradenitis suppurative. Another, the Owl Medical Turn Timer, is a retrofittable bed-mounted system that uses low-cost sensors to determine when it’s time for a healthcare professional to turn a patient. “There are existing systems out there,” Ku says, “but they’re a lot more expensive and require special beds. This one allows visiting family to share in the responsibility by making it easy for them to read the monitoring system and to alert a nurse.” The team behind its development has filed for a patent, he adds.

The work may not be as hip as prototyping the newest iPhone or as sexy as fashioning the latest Ferrari, but for Ku—and by extension, his students—design thinking is all about teasing out answers (from patients and healthcare professionals) to questions like “What keeps you up at night?” and “What bothers you?” and then figuring out solutions.

On a larger scale, for example, some students have worked on improving the workflow and communications of emergency room departments. Guided by architects at KieranTimberlake [“A Passion for Putting Things Together,” Nov|Dec 2003], who developed an analytic program to investigate how spatial layouts affect interaction among nurses and doctors in the ER, the students shadowed personnel and logged their movements, actions, and interactions.

“We learned that one shift nurse interacted with a physician during only six percent of her time,” Ku points out. “That’s surprising for what is supposed to be team-based care.”

For now, the research remains experimental. “The next step is to apply the findings to a specific clinical problem,” Ku says. “But this is not easy work.”

Born in Chicago to Korean immigrants—“who probably brainwashed me into becoming a physician,” he says wryly—Ku chose to specialize in emergency medicine because the notion of equal treatment for all appealed to his sense of social justice. Having majored in classical and ancient studies at Penn and earned his medical degree from Penn State, he entertained thoughts of working in the public sector, going so far as to earn a master’s in public policy at Princeton.

But he soon realized that his real love is being a clinician. “My favorite parts of the week are still my two overnight shifts,” he acknowledges. And when Jefferson’s dean, Mark Tykocinski, challenged him to help him “change the future of medicine,” Ku jumped in with the same enthusiasm that he brings to surfing, snowboarding, and skateboarding.

“I basically did an ethnography,” he laughs. “I visited architectural studios and other designer spaces to understand how creative people work and generate ideas.”

Ku was oddly prescient in conceiving a design track. Last July, Jefferson merged with Philadelphia University, a small liberal arts school with strong architecture, graphic design, and fashion design programs.

“That’s really helped the program,” Ku says. “The opportunities for collaboration are endless. We’re working to develop different types of medical education so we can attract different types of students. The standard medical pedagogy of memorizing vast quantities of information hasn’t changed in 100 years. But thanks to artificial intelligence and the internet, patients already don’t need physicians for that as much as they once did. Instead, I believe that one of the most important skill sets a physician will offer will be listening—and creatively solving problems.”

—JoAnn Greco