The former libraries director led Penn’s system into the digital age, without neglecting print and while greatly improving library spaces along the way.

After 43 years at Penn, including 14 as vice provost and director of libraries, H. Carton Rogers III retired on June 30, 2018. But he’s still around—in a bit more than spirit. The libraries’ board of overseers and Orrery Society Council have recognized his service by endowing the position in his name with a $3 million gift.

“I was totally bowled over,” he said in a May interview in Van Pelt Library. “I’m honored in ways that I can’t even begin to articulate.” Also a little guilty about the resulting mouthful of a title: “I feel sorry for the library directors who have to be The H. Carton Rogers III Director of Libraries.” (The first to bear that burden—Constantia Constantinou, formerly dean of university libraries at SUNY-Stonybrook—takes up the position August 1.)

During his time at Penn, Rogers witnessed—and in large part led—the libraries’ transition into the information age, trading the card catalog for the computer screen, while continuing to build the libraries’ print collections and other physical holdings. He also oversaw major renovations to library facilities, with projects like the Weigle Information Commons, the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books, and Manuscripts [“Gazetteer,” July|Aug 2013], and the Moelis Family Grand Reading Room, an elegantly designed, quiet study space that opened last summer on Van Pelt’s first floor.

Rogers remembered hanging out in his local library growing up in Schenectady, New York, but his sense of the value of libraries—and the idea that he might make a career working in them—first came into focus at Marietta College in Marietta, Ohio, during the late 1960s. “My campus was pretty active and pretty split during that period, and I found real sanctuary in my college library,” he said. “I also liked the fact that, even though the college was fairly conservative, [and] the state was fairly conservative, the library was a bastion of free speech. They had newspapers and magazines that crisscrossed the political spectrum.”

Ohio was an early center for library automation—today’s Online Computer Library Center (OCLC), “a global library cooperative,” was originally the Ohio College Library Center, and began as an effort to develop a computerized network for school libraries in the state. “I was intrigued by the use of emerging technologies in the library context and decided that I’d go in that direction,” said Rogers, who earned his master’s in library science from Drexel University.

Coming to Penn in 1975, Rogers recalled that his first job, in the Biomedical Library, was really two jobs, with responsibility for both public services and technical services. “In those days, Penn’s financial situation was a little rocky,” he said wryly. “If I’m remembering correctly, they didn’t have enough money to hire two people, so they combined the positions.” A bargain for the University, certainly, but also “a really terrific learning experience,” he said. “I was able to hone my skills before coming over to the main library and becoming part of the senior leadership team.” He was in charge of information processing and collections development and management at the time he took on the role of vice provost and director.

The University was one of the first libraries on the East Coast to install an OCLC terminal and, even before his arrival, had implemented a “very primitive online circulation system,” Rogers said. “If you go up into our stacks, you will still see books with punch cards in the back that were circulated using [it].”

The library’s first online system was implemented in the late 1980s,“but we waited a long time to dismantle the card catalog because, of course, one of the challenges that great research libraries have is the fact that you have this legacy data that you have to move from print to digital.”

The pace of change picked up considerably after Rogers took on the libraries’ top job in 2004. Facebook launched that year. Google went public. YouTube launched a year later. “This is when the whole information environment turned upside down, basically,” he said. “Before that we were somewhat in control of the way we used technology, the kinds of technologies that we introduced. Once Google hit and people started to change their information-seeking behaviors, libraries really had to adapt.”

Meeting users’ changed expectations is a continuing challenge. “I wish you could search our online catalog as easily as you can search Google. But those technologies aren’t readily available to us.” This past year the library swapped its 20-year-old management system for a state-of-the-art replacement that “improved things dramatically,” Rogers said, adding ruefully, “but how long is anything state-of-the-art anymore?”

For many library users “our print collections remain extraordinarily important. In other disciplines, nobody is paying any attention to print material at all, or very little attention,” he said. “How do you manage the infrastructure necessary to support both the physical and digital?”

The swift progression from VHS to DVD to streaming video is a vivid example of the challenges involved. “Within my 14 years as director we’ve transitioned right out of the physical state into the ether with movies.” Similarly, while the library’s music collections encompass a variety of formats, “what’s getting used most these days are our streaming services,” he added.

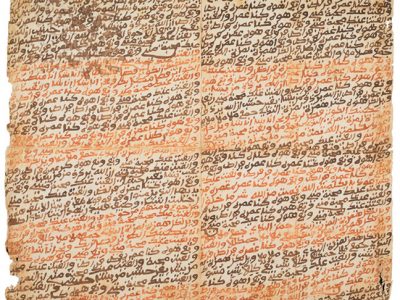

Penn has also been busily digitizing many types of—non-copyrighted—materials (“I don’t want to spend my dotage in jail,” Rogers joked). “We’ve digitized all of our medieval manuscripts. We’ve digitized all of our Indic language manuscripts. We just have a whole raft of material waiting to be digitized.” The University also collaborates with other library institutions to seek funding for digitizing large troves of similar kinds of material—and it is dedicated to open access. “Anything that we digitize we want to make freely available to the world, and we think that’s an important part of our mandate.”

Penn is part of the HathiTrust, sharing its own digital material and in turn offering “access to the Penn community to this large trove of digitized material that’s coming in from libraries across the world,” he said. “And that’s made a huge difference. The ability to find digitized material through our OPAC [online public access catalog] has just expanded dramatically ever since we loaded these HathiTrust records into the database.”

Rogers presided over not only the familiar Van Pelt-Dietrich and Fisher Fine Arts Libraries but also a variety of special collections, departmental, and professonal libaries on campus (all but the law school library, which reports to the dean), plus the library of the Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies downtown and a storage facility in New Jersey, where about 2.5 million of the system’s 7 million print volumes are kept at any one time.

Upgrading the old Biomedical Library, where Rogers got his start, is a major focus of the recently announced Power of Penn campaign [“Gazetteer,” May|June 2018], for which the libraries are seeking to raise $40 million overall. “If I have any regrets leaving, it’s that I wasn’t able to finish the renovation project for that library—because I have very fond memories of working in there, and I feel like it’s really an important crossroads library for Penn,” he said. “We’re calling the project the Biotech Commons, because it does represent a library that really supports the kind of interdisciplinary work that we all talk about at Penn.”

In addition to that project, Rogers pointed to “evergreen” needs for funds to support collections “in all formats,” which is the focus of the library’s Orrery Society. “One of the things that has plagued research libraries in recent years is the continuing high cost of information,” where inflation is much higher than “almost anywhere else in the economy.” Despite considerable progress, Penn’s libraries are still a “long way away from some of our competitors—the Princetons, Yales, and Harvards—in terms of the endowment income that comes into their coffers every year.”

Rogers declared himself “really bullish on libraries, even after 43 years in the profession.” Dire predictions of obsolescence have faded as libraries have been reimagined to focus on “using our spaces as ways of driving new and different services,” he said.

He didn’t have a “snappy answer” for his post-retirement plans, but they involved travel with his wife, time with his grandchildren, some volunteer work, and reading “the thousands of books that I haven’t read.”

“I’ve been really, really fortunate to work at Penn,” he said. “I’ve been fortunate to watch Penn grow from an institution that hired me to fill two jobs, to this world-class university that we work in today.”

He credited as mentors “three really extraordinary librarians”: former libraries director Richard DeGennaro, deputy director Joan Gotwals CW’56 G’58 Gr’63, and associate director Bernard Ford. “I learned so much from them.” Of today’s staff, he said, “You’d be both amazed and impressed with the variety of experiences that they bring” to the community, which “augurs well for the libraries’ future, and, frankly, for Penn’s future.”

Recalling his “many, many different positions in the Penn libraries,” Rogers says, “the joke always is that, ‘Yeah, he knows where every book is.’ And it does feel that way at some point. But it’s just been an exciting ride. If you’re going to work in a research library, there aren’t many that I’d rather be in than Penn’s, believe me. And I think the libraries have come a long way, too, in the last 43 years. Again, it’s been great to be part of that.”—JP

I have used Van Pelt for more than five decades and its renovations under Carton’s leadership are really superb. Bravo and thanks.

Stephen Marmon 71C, 81WG