The visitor’s eye is drawn to the black-and-white photographic mural that covers most of a wall in the Institute for Contemporary Art. The slightly disorienting piece depicts a night scene from the 1930s: a shoulder-to-shoulder crowd, men in fedoras, women in fashionable jackets, and one guy, cigarette in mouth and a beret on his head, looking into the camera. In the center, a handful of people are gazing upwards at a … naked branching tree.

This work, by Los Angeles artist Ken Gonzales-Day, is titled “St. James Park (The Wonder Gaze),” from his “Erased Lynching” series. Though it is based on a 1933 postcard photo of a lynching in San Jose, California, all traces of the crime have been obliterated in Gonzalez-Day’s version, making the photograph more approachable than it otherwise would have been, especially at this overblown size. Thus engaged, the viewer might notice that something else is missing: evidence that anything unseemly is going on.

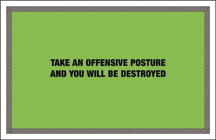

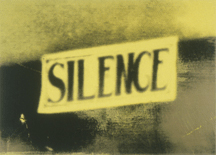

“Crimes of Omission,” which ran through August 5 at the ICA and was curated by a group of 10 Penn undergraduates, was brimming with diverse and compelling forms. Bright postcards, colorful paintings, a chromogenic print, a silkscreened yellow sign, and what looks like a sheath of gold enamel—all soothe the eye, but hide the crime. The exhibition vividly demonstrated how art can draw attention to injustices that go unnoticed in the course of daily life.

London artist Freddie Robins, for example, used knitting to convey her message. Inside each whimsically knitted replica of a real house, the viewer was invited to consider a high-profile murder committed by a woman in the original home. The crimes were missing from the art, but described in the annotations: “Styllou Christofi, a 52-year-old Cypriot woman, murdered her German daughter-in-law, Hella, at the family home on 28 July 1954. Styllou had moved from Cyprus to live with her son and his family but problems soon arose. Styllou became increasingly jealous of her daughter-in-law and ended up hitting her over the head with an ash-plate from the stove …” (from “Knitted Homes of Crime, 2002”).

Feast your eyes on knitting and end up contemplating murder: That’s the kind of response the student curators had in mind, according to one of them, Kristen Beneduce C’08.

“One discussion we had was about the idea being revealed after you really look at the piece,” she explains. “It’s beautiful or fun, but then has an alternative motive. We hoped the art would allow people to go somewhere else, taking them back to the world.”

And the world can be an unsettling place. Trevor Paglen’s piece “Missing Persons, 2006,” displays evidence of the CIA’s “extraordinary rendition” program, in which terrorist suspects from around the world can be detained and transported to undisclosed locations for interrogation and torture without legal recourse. From business records, aircraft registrations, and corporate filings, Paglen collected repeated, sometimes blatantly unmatching, signatures of nonexistent people representing front companies that own the fleet of unmarked planes used for that purpose.

The exhibition was the result of a year of study and work on the part of Loren Appin C’07, Julia Berenson C’07, Brittni Busch C’07, Morgan Greenhouse Nu’07 C’07, Alexandra Lenobel EAS’07 C’07, Jenna Moss C’07, Alexandra Nemerov C’07, Vincent Szwajkowski C’07, Alex Tryon C’08, and Beneduce. All of them were part of “Contemporary Art and the Art of Curating,” a collaboration between the ICA and the Department of Art History that represents the only undergraduate seminar of its kind in the country. It was taught by Dr. Richard Meyer, professor of contemporary art; alumni trustee Katherine Stein Sachs CW’69; and Keith Sachs W’67, visiting professor of art history, with help from Liliana Mikova (Ph.D. candidate in art history), and Naomi Beckwith, a Whitney Lauder Curatorial Fellow.

The students immersed themselves in the study of contemporary art, not only through reading but also through travel. They visited galleries, corporate collections, private collections, small museums, and artists’ studios in Philadelphia, New York, and Pittsburgh. Their personal research included Thanksgiving-break visits to exhibitions in their far-flung home cities; on returning to campus, they discussed what the works meant to them, and proposed themes. When they had finally narrowed the choice of themes down to three, they voted—then dug back in for more focused research.

During the second semester they curated the exhibition, working with ICA staff and the artists. Logistical challenges, from budgeting to shipping pieces to installing works, were met as they arose.

Two artists whose work the curators wanted to display, Susan Stilton and Gonzales-Day, created pieces especially for the exhibition and attended the opening. Trevor Paglen traveled from Berkeley to participate in the discussion engendered by his work. (Funding sources for the seminar, curating project, and exhibition included the RBSL Bergman Foundation and the Dolfinger-McMahon Foundation.)

“It was invaluable hands-on experience, especially at a premier art venue like ICA,” said Beneduce, one of two juniors taking the senior-dominated seminar. “It’s one of the first things I’ll mention in a job interview.”

For the students who don’t intend to pursue careers in art, Beneduce points out, the benefit is in knowing firsthand the kind of research that goes into building a collection for personal gratification and investment purposes, as well as gaining a solid basis for understanding modern and contemporary art. They might also find themselves looking a little more closely at the seemingly innocent world around them.

—Cynthia McLemore