Two ICA exhibitions explore form and belonging.

David Antonio Cruz was feeling overwhelmed. On a rainy September evening at Penn’s Institute of Contemporary Art, he was surrounded by members of his “chosen family,” the very friends and intimates celebrated in the portraiture of David Antonio Cruz: When the Children Come Home. This was, in fact, a homecoming for the North Philadelphia native and New York City resident—both his first Philadelphia exhibition and his first solo museum show.

“With this exhibition,” Hallie Ringle, the Daniel and Brett Sundheim Chief Curator at the ICA, said at the opening reception, “Cruz joins the ranks of Andy Warhol, [the sculptor] Teresita Fernández, and so many other important artists who have had their first solo shows here at ICA. And like the artists that came before him, David Antonio pushes the boundaries of contemporary art.”

Cruz’s colorful, playful group portraits are infused with local references and magical realism. They build on and subvert the figurative tradition that influenced him—artists from Goya and Velázquez to Thomas Eakins, Henry Ossawa Tanner, and Diego Rivera. In more than 20 paintings and drawings at the ICA, bodies are entangled, and faces and figures (including self-portraits) are often upside down. Men and women, in a richly saturated spectrum of skin tones, caress one another. Puerto Rican Pieta, from 2006, depicts Cruz lying on his mother’s lap as she embraces him.

“Chosen family is something that is the core, the foundation, of queer community,” said Cruz, a 48-year-old assistant professor of visual arts at Columbia University who has exhibited at New York’s El Museo del Barrio and the Smithsonian Institution’s National Portrait Gallery. “It’s how folks have survived throughout the years. It’s come out of necessity for support, for housing, for love.”

The Yale-educated Cruz sought to document the history of his North Philadelphia community as the pandemic closed gathering places and disrupted connections and relationships. He began with conversations. “I think about history and how things are erased,” he said. “I was constantly going back and looking at the threads that were disappearing and being pushed aside.”

Some of Cruz’s recent paintings depict subjects encased in what look like transparent helmets or globes, evoking astronauts. The images, he said, embody “the fiction of future possibility.” Art, he reflected, is “a way of fixing time.” In his portraits, “there’s a sense of preservation: What is it to preserve a body? What is it to preserve a history, especially when it comes to people of color?”

When the Children Come Home, featuring an October 22 performance by Cruz, took shape in collaboration with the exhibition curator, Monique Long. Long grew up near Cruz in North Philadelphia but only met him years later in New York.

“I wanted to respond to the architecture of the gallery and also highlight David’s painting mastery,” said Long. “These works exemplify some of his major concerns: constructed family, touch, kinship. You can see his subjects abide with one another. You can feel the love between his friends.”

One gallery houses a site-specific installation with a circular settee, paintings, fanciful constructed objects that Cruz uses in performance pieces, and glittering chandeliers that serve as a recurrent motif in his art. The wallpaper, Long said, was inspired by the landscape of Greenmount Cemetery, where members of both her family and Cruz’s are buried. “Quite emotional,” said Long. “Our hope is that people will spend a lot of time here and sit with the work and reflect and contemplate the space. All the pieces speak to autobiography and home and respite.”

The furniture in the Cruz show ties in with a concurrent exhibition at the ICA, Moveables, also on view through December 17. A group show of five artists, Moveables explores the tensions between organic and inorganic forms, sculpture and furniture, in installations that seem to bleed into one another.

The exhibition is cocurated by former ICA senior curator Alex Klein, now head curator and director of curatorial affairs at The Contemporary Austin, and Cole Akers, curator and associate director of special projects at The Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut.

According to the curators, Moveables is part of a lineage of ICA exhibitions, including Improbable Furniture (1977) and Ruffneck Constructivists (2014), that challenge histories of modernist design by introducing considerations of sexuality, race, class, gender, and ability. “The show is really just a love letter to ICA’s history,” Klein said. It stresses the idea of “theatricality,” she added, encouraging visitors to see themselves “as performers in the space.”

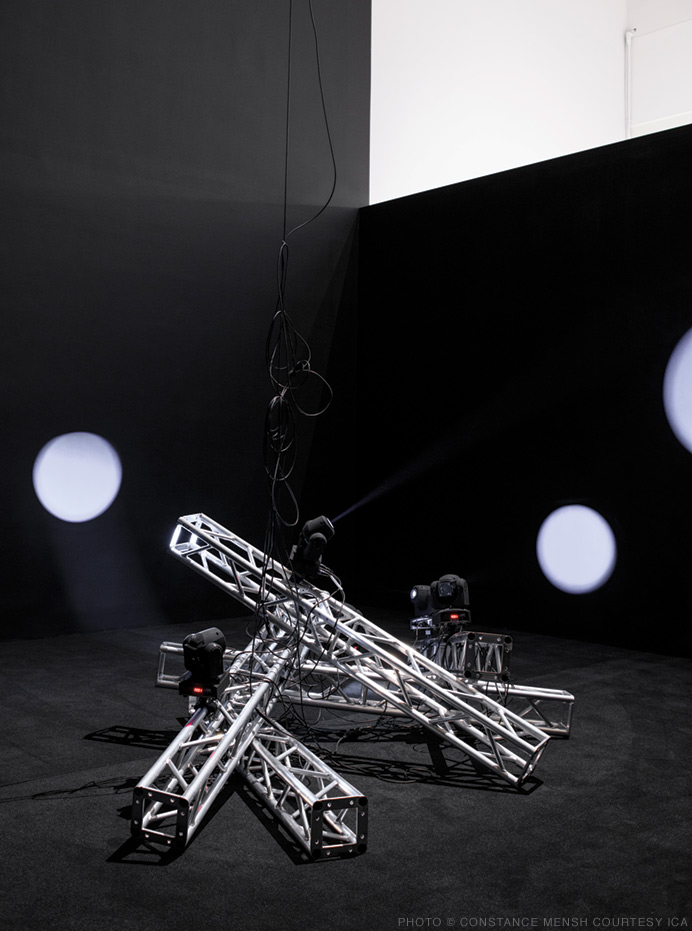

Nikita Gale’s PRIVATE DANCER is a kinetic light sculpture that moves in time to Tina Turner’s unheard song. Jes Fan, who works in Brooklyn and Hong Kong, combines hand-blown glass forms with aqua resin casts of sections of human bodies, including his own, injected with materials such as testosterone, estrogen, and sweat. “He’s really interested in troubling this tension between biology and identity,” Akers said.

Hannah Levy’s steel and silicone sculptures marry industrial design and organic forms. One example is a monumental chandelier-like sculpture with claw-like protrusions—a link, Levy noted, to Cruz’s show. She said her work reflects “unspoken social values,” including the idea of a chandelier as a marker of class status.

Oren Pinhassi’s fantastical sculptures reference historical shapes and sometimes incorporate quotidian items, such as toothbrushes and umbrellas. “The reason to make sculpture is to imagine different possibilities for thinking about architecture and structure,” he said.

Moveables is anchored by three “furniture sculptures” by Ken Lum, the Marilyn Jordan Taylor Presidential Professor and chair of Fine Arts at Penn’s Stuart Weitzman School of Design. Lum, whose work has been included in the Whitney Biennial, the Venice Biennale, and other international exhibitions, said these pieces are his first to be shown at the ICA.

The simplest sculpture is The Lone Ottoman, which is just what its title indicates. Lum reclaimed it from the installation process, during which it served as a repository for tools. He relishes its linguistic evocation of the Ottoman empire and called it “a discreet marker of difference.”

The Photographer or The Mirror? and The Curse is Come Upon Me consist of living room seating that juts up against mirrors, both drawing viewers in and shutting them out. “I was always interested in the way in which conversational spaces were configured,” Lum said. “There’s always this idea of enclosure.”

He cited Minimalism as an influence. “Minimal art purports to be abstract,” he says, “but actually it’s imbued with alienating features because you can’t relate to it on a representational level.” In fact, it’s “an expression of alienation.”

Conceptual art is another touchstone. “I was always interested in works of art calling attention to themselves, including calling attention to the way we experience a work of art,” Lum said. “In the act of looking at the work of art, you actually can see yourself engaged in that act. And at the same time, you can see other people engaged in it. So there’s a constant kind of reflection upon reflection.”

—Julia M. Klein