A new exhibition at the Arthur Ross Gallery showcases an alumnus’s powerful collection of modern Mexican art.

By Samuel Hughes

I wish I could have gone with Harry Pollak W’42 and his late wife, Sharley, when they visited the studios of Alfredo Zalce and Juan O’Gorman and the other Mexican artists whose work they collected. I picture them stepping out of the hot sun of Morelia or Mexico City and into the quiet, earthy places where the art is made and the imagination is strong and the smell of paint and linseed oil mixes with that of coffee and corn masa …

“I preferred to buy that way, actually,” says Pollak in a telephone interview. “I went to the artists’ homes on numerous occasions, and made friends with some of them. I was usually invited for lunch. I think they really felt complimented that somebody was interested in their work.”

Since Mexico is not an option right now, and the auctions at Sotheby’s and Christie’s are too rich for my blood, I’ll go instead to the Arthur Ross Gallery, where “Travels in the Labyrinth: Mexican Art in the Pollak Collection” is being exhibited from September 1 through December 9. (The title was inspired by an essay in the show’s gorgeous catalogue, published by the University of Pennsylvania Press.) The traveling exhibition, which first opened at the Naples Museum of Art in Florida, consists of more than 100 works of art—painting, sculpture, and drawings—most of them powerful, vibrant, mysterious. After it leaves Penn, it will travel to the Ulrich Museum of Art at Wichita State University in Kansas.

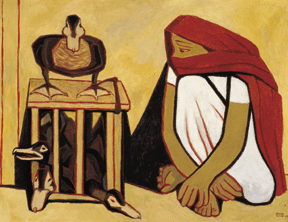

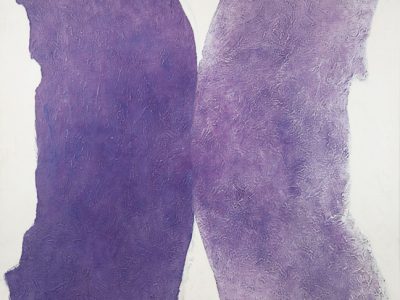

As the works shown on these pages indicate, the range of styles and subject matter by the 46 artists is impressive: from the earthy scenes of Gabriel Fernández Ledesma and Alfredo Zalce to the wry cubism of Rufino Tamayo to the sculpture of Armando Amaya and Alfredo Castañeda. Not to mention the engaging retablos, or ex votos—simple, compelling paintings of divine interventions in the lives of ordinary people, accompanied by a hand-written description of the event by the anonymous artist.

For a variety of reasons, most Americans know little about Mexican art beyond a few big names: typically Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, and maybe David Siqueiros, who was such a powerful influence on Jackson Pollack; or Gerardo Murillo, the legendary “Dr. Atl”; or José Clemente Orozco. But for art-lovers to overlook the rest of the spectrum, says Pollak, is a big mistake.

“They’re missing an awful lot. Not taking anything away from the greatness of Rivera and Tamayo et cetera, but there are others just as important.”

Thirty-five years ago, when the Pollaks began to collect art in a serious way, they decided to confine themselves to Mexico.

“I really liked the Mexicans the best,” says Pollak, “because they were recognized world figures in the world of art and my feeling was that they were extremely cheap. I had a lot of reasons to believe that.”

By then they had been traveling to Mexico from their home in Wichita, Kansas, for a decade. (Pollak now lives in Longboat Key, Fla.) Having spent some time in Morelia, in the west-central province of Michoacan, they had been captivated by some of the art they had seen. They had even bought a few pieces, more as travel mementos than as real collecting. Gradually, they got serious about it, and spent a couple of years studying the subject intensively before they began to frequent galleries in Mexico City.

“I came to the realization that to collect successfully, knowledge of your subject was the best tool you could have,” says Pollak, adding that when he began studying it seriously, “I felt that it was just a miniscule part of world art, and I could absolutely master the subject.”

He laughs quietly at his own hubris. “After 35 years, I’m proud to state that my knowledge is at best superficial. It’s an enormous, enormous subject. One artist is a life-time endeavor.”

“He is very modest about it,” says Dr. Dilys Winegrad Gr’70, director and curator of the Arthur Ross Gallery and editor of the catalogue. “He says ‘Oh, I don’t know anything about this,’ and so on, but he knows a great deal about the subject matter, and it’s very clear that he’s read everything he can get his hands on.”

All of the artists the Pollaks collected were born by 1940, which puts them in the modern category rather than the contemporary. Although Pollak was advised by experts in the field, Winegrad points out, “as in all private collections, there is a big element of the collector’s taste.”

But that taste is “very universal,” she adds, “and I think people will love the fact that it does have a lot of very Mexican-looking work.”

That certainly describes the Pollaks’ first twin-purchase in 1965, from the Galer’a de Arte Moderna in Mexico City: Zalce’s Vendadora de Patos (“Girl Selling Ducks”) and Leñador (“Woodcutter”). When they found out that Zalce was from Morelia, they began to visit him in his studio and bring him hard-to-find brushes and tobacco. Over the years, they continued to buy his paintings. (Zalce, now 93, is still alive.)

“We collected for our own pleasure,” Pollak points out, “and as a result, we seemed to collect the same kind of pictures over and over, the same artists over and over. Either you like them or you don’t. The artists you really like, you always want more.”

Although Marcia Corbino’s essay in the catalogue mentions that Pollak had taken art-appreciation courses while a student at Penn, he admits that he barely remembers them. “I’ve always been kind of an art buff, and always been a museum-goer, ever since I can remember,” he says. Yet he is emphatic that his wife was more discriminating than he, and regards the catalogue as a tribute to her collecting talents.

“She had the best taste,” he says matter-of-factly. “There’s no question of that. She was very discerning. Generally, she would do the selecting, and I would do the economics. Ninety percent of the time, I liked what she liked, but once in a while I didn’t, and if I didn’t, we wouldn’t buy it.

“Interestingly enough, when I’m complimented on a picture by somebody who’s very knowledgeable, invariably it’s one of the pieces that she was involved in the selection,” he adds. “I don’t get too much commentary about the ones I picked out.”

Pollak has a special place in his heart for the votive offerings known as retablos, which are usually oils painted on tin, and most often the work of anonymous artists commissioned to depict a particular event. While the text of many retablos is faded, Pollak writes in an essay for the catalogue, “what remains is the freshness of the experience and the profound faith in divine intervention applied and received.”

“The retablos stand on their own,” he says. “It’s hard to explain what the appeal is—I don’t think it’s visual, really. It’s the overall thing. There are actually people in Mexico today that have the utmost faith in these retablos. They’re not in the cities; they’re out in the country. They believe strongly that retablos really work—that if you have a problem, there’s a superior being you can appeal to that will intervene, save your life and help you. The faith of the Mexican is an overwhelming thing, and to have that faith displayed in a way that is collectible adds an extra dimension.

“Incidentally, retablos are coming into their own,” he adds. “I never paid over $50 for a retablo. Now they’re auctioning off in the thousands. But they were hard to find, the good ones. We spent a lot of time looking for them, and one at a time, we were able to get them.”

Time—and money—well spent.