Help and community for those who have “huddled, heaved, hurled, sweated, palpitated, and hyperventilated” through life.

From the moment they met at Penn, Maggie Sarachek C’89 and Abbe Greenberg C’88 sensed they were kindred spirits. “I think we both recognized panic on each other’s faces and became instantly connected,” Greenberg says. “We started sharing our struggles immediately.”

Sarachek had suffered stomach problems for years, while Greenberg experienced heart palpitations and shortness of breath—symptoms of anxiety, though they didn’t fully realize that at the time. “The vocabulary wasn’t there,” Greenberg says.

Today Sarachek, a former social worker in Ohio, and Greenberg, a former professor of communication in New Jersey, are the Anxiety Sisters, Abs and Mags. They speak at conferences, host a podcast called The Spin Cycle, run an active Facebook page with nearly 200,000 followers, offer coaching and support, and collaborate with national mental health organizations—including Active Minds, founded by Alison Malmon C’03 [“Alumni Profiles,” Sep|Oct 2020]. In September, they published their first book, The Anxiety Sisters’ Survival Guide: How You Can Become More Hopeful, Connected, and Happy (TarcherPerigee).

In a world where anxiety, panic, and mental illness are misunderstood, stigmatized, and full of “solutions” that often exacerbate the problem, the Anxiety Sisters provide a place and a platform for those who, like them, have “huddled, heaved, hurled, sweated, palpitated, and hyperventilated our way through life,” as they write in the introduction.

Greenberg and Sarachek joke that, while everyone else was pledging a sorority at Penn, they were being hazed by anxiety into their own. That sense of sisterhood continued after graduation. “We stayed each other’s touchstone and battled our anxiety side by side,” Greenberg says.

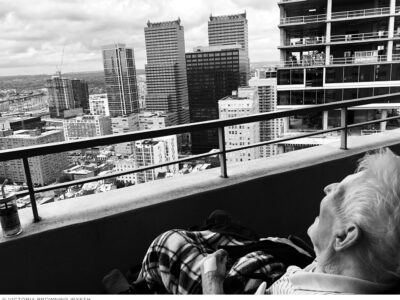

They call the 1990s their “Decade of the -Ists,” visiting therapists, hypnotists, psychiatrists, acupuncturists, and so on. They experienced separate phobias and grew so panicked there were times each had trouble leaving their homes. Sarachek recalls living on the 16th floor of a New York City apartment building and being terrified to get in the elevator. They sought out books about anxiety but found them all clinical and prescriptive, not user-friendly.

“I needed an Ativan to look through the Barnes & Noble section on anxiety,” Sarachek recalls. “It would be all, ‘You should be doing this; you shouldn’t be doing that.’ There was that whole should-storm.”

“One book I picked up was telling me that to overcome my panic I needed to do 30 minutes of intense cardiovascular exercise every day,” Greenberg adds. “My heart rate was already through the roof. I couldn’t possibly be more sweaty and shaky than I already was.”

Their anxiety and phobias led to what they call “shrinking-world syndrome,” in which sufferers feel they can do less and less, go to fewer places, see fewer people, occupy less space. Once, while panicking and sick to her stomach en route to a friend’s wedding, Sarachek made a U-turn—or rather, she says, her anxiety told her to make a U-turn and she obeyed. “The stomachache went away, but so did the friendship,” she says. “That’s where the stigma really is. Everyone feels comfortable talking about how, ‘It’s OK to be anxious.’ But when it comes into life, into things that people really struggle with on a day-to-day basis, people lose some of that openness, because it affects them.”

“The biggest misconception about anxiety is that it’s an excuse,” Greenberg says. “We tell people, ‘It’s a disorder, not a decision.’ But it’s not like [having] a broken leg. If you’re wearing a cast, people are going to bring you a casserole because they’re concerned you won’t be able to get yourself dinner. If you have crippling anxiety, people say, ‘Buck up, chill out.’ It’s invisible, there’s no blood test for it. So that takes away the legitimacy from it.”

In 2010, on a bus ride from New Jersey to Manhattan, they were talking about the side effects of anxiety medications when a woman turned around. “I take that same medicine,” she said. “What do you do about those side effects?”

Soon, more women were chiming in, talking about antidepressants and anxiety. When they disembarked, Greenberg asked Sarachek, “Can you believe how many total strangers were talking about something so intimate?”

Sarachek, they recall, replied, “This is such a lonely disorder,” and on 9th Avenue declared, “We’re Anxiety Sisters!”

They launched their online community in 2017 and now reach thousands of people every week. Their website (anxietysisters.com) features a special “Help! I’m Having a Panic Attack” button that links to a recording of Greenberg offering the listener empathy and guiding them through a breathing exercise. The panic button, they say, gets pressed approximately 1,500 times a week. With the Survival Guide, they hope to offer fellow Anxiety Sisters the type of between-the-pages resources they weren’t able to find when they went looking.

They note that they often see middle-aged women who are not aware that their symptoms—shortness of breath, becoming flushed, heart palpitations, stomach cramps—are physical manifestations of anxiety. But they emphasize that anyone of any age or gender can be an Anxiety Sister. (“The concept of sisterhood in our minds refers to community in general,” they write, “but ‘Anxiety Community’ just isn’t that catchy.”)

“We want to be your girlfriends who happen to be experts in anxiety,” Greenberg says. “We want to help normalize your situation, destigmatize it, make you feel OK. We are living proof that you can thrive with anxiety. We both still have some anxious days in our life, but we’ve learned to live well with our anxiety. We want other people to see that’s possible and that’s something that we can do together.”

Community, they say, is essential. “I remember taking social psychology at Penn with Professor John Sabini [“Obituaries,” Jan|Feb 2006], and he started the very first lecture off by saying, ‘Human beings are social animals.’ We tell people: You have to make community part of your treatment plan in general,” Greenberg says.

“The beautiful thing we see happening all the time is people saying, ‘I felt like this was only me,’” Sarachek says. “Then when you see 50 other people have had that same experience, you realize, this happens, this is part of anxiety.”

They’ve created their own vocabulary to help anxiety feel less threatening: spinning for panic, for example, or floating for disassociation.

“We’ve tried to find a way to be a bridge between the clinical literature and our people,” Greenberg says. “We are familiar with all the medical jargon. We read neuroscience news, we’ve taken courses and educated ourselves in the field. But we really try to find a way to make it less scary for people. People get panicky hearing the word panic.”

“The way we discuss anxiety is not anxiety-producing, because we totally understand what you mean,” Sarachek says.

For the Survival Guide, they wanted to eschew the shoulds. Instead, their goal with the book—and with the Anxiety Sisters in general—is to be relatable and real, providing an arsenal of techniques and strategies for combatting anxiety, but framed as “here are a whole slew of options,” with available modifications, not “here’s what you should do.”

They wrote the book over the course of five months in 2020, working seven days a week while the pandemic raged and both were in lockdown mode. “Our anxiety had us convinced, even though neither one of us would leave our houses, that we would end up with COVID,” Sarachek says.

Pre-pandemic, they traveled the country offering workshops and retreats—and look forward to resuming them as soon as it’s safe to do so.

“When we teach people about anxiety, we don’t teach them how to get rid of their anxiety,” Greenberg says. “We teach them how to manage it so they’re in the driver’s seat, they make their own choices. We try to teach people what we’ve learned, which is how to live really well with it. How to keep it from shrinking your world. It doesn’t mean you aren’t going to have a bad day. We have bad days.”

In turn, they are inspired by the example of all the Anxiety Sisters out there trying to do just that. “Every day I hear stories and I see how much people, no matter what, will strive to move forward and to connect and be kind,” Sarachek says. “I think that is one of the things that has helped me the most. People are supporting each other so much and it is so healing to see that—in this world, to watch people reach out and say, ‘Yeah, I know what that feels like, I’ve been there too.’”

—Holly Leber Simmons