Recalling their near-weekly conversations over the two-and-a-half years before mental health pioneer Aaron T. Beck’s death at age 100, the author—possible biographer, irritating interviewer, admiring friend—bears witness to the founder of cognitive therapy’s ceaseless quest to live a “rich full life.”

By Stephen Fried | Photography by Victoria Browning Wyeth

It was the last Saturday in October—we always talked on Saturdays at 11 a.m. I had just finished another in a long series of fascinating and challenging “maybe last conversations” with Tim Beck, the founding father of cognitive therapy, arguably the most important figure in mental health since Sigmund Freud and, at the age of 100 years, three months and 12 days, if not the hardest-working man in the history of medicine, then certainly the longest-working.

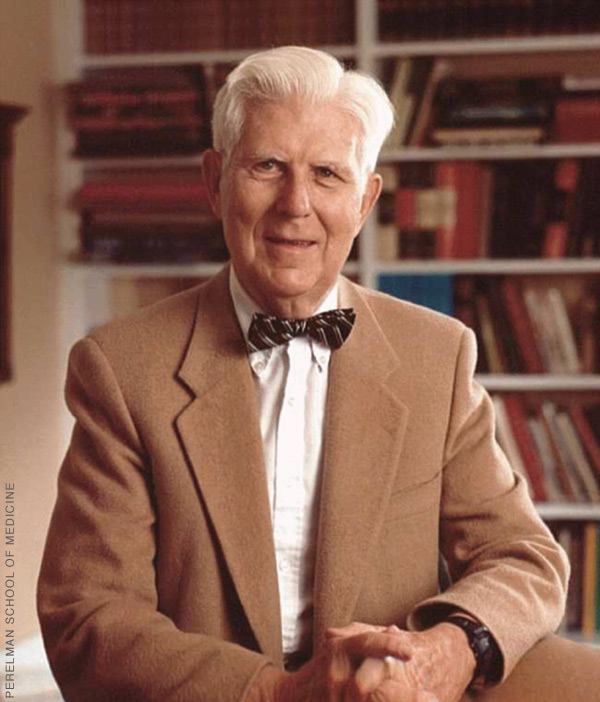

Aaron Temkin Beck Hon’07, “Tim” to his friends, had refused to retire at so many milestones that the thousands of psychologists and psychiatrists he trained or inspired didn’t know what else they could do to honor him. “He’s had more festschrifts”—writing collections honoring an esteemed colleague—“than anyone I ever heard of,” joked Oxford psychologist David Clark, one of two accomplished Beck proteges with this same name.

A two-time finalist for the Nobel Prize, Beck won the top honor given in American medicine, the $100,000 Albert Lasker Clinical Medical Research Award, when he was 85. More recently, when he was 96, the online medical journal Medscape named him one of the 25 most important physicians of the past century. Beck came in fourth, behind Watson & Crick (for DNA), Jonas Salk (for eradicating polio), and Benjamin Spock (for revolutionizing child-rearing). He was ahead of Carl Jung, Elizabeth Kubler-Ross, and several Nobel laureates for revolutionizing talk therapy with Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, and revolutionizing mental health diagnosis by developing the first important inventory—a series of questions everyone would use and score the answers the same way—to assess the existence and severity of depression (and later anxiety, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation). Even though Beck had, in recent years, become all but blind because of glaucoma (he could still see a tiny bit out of the side of his left eye) and mostly bedridden (especially frustrating after playing tennis well into his 80s), he was still working through his latest brainstorms. They mostly concerned what he called the “radical shift” in his thinking during the 90s (that’s his 90s, not the 1990s), leading to a retrofitted form of cognitive therapy he called “recovery oriented” and labelled CT-R. Instead of being used for moderate symptoms in outpatients, CT-R was meant for long-hospitalized patients with schizophrenia and other severe mental illnesses.

On any given day, Beck could wake up wanting to think through almost anything—a new theory about what psychosis really is, or whether the poles in bipolar disorder needed to be reconsidered, or a grand unifying principle of psychology and psychiatry, or an argument against deeming then-President Trump mentally ill. Beck was still overseeing post-docs, coauthoring books, dictating papers, and carrying on daily correspondence—all with the help of two overworked but devoted assistants, a dictation service, an Alexa speaker, and his beloved pale green iPhone, which he clutched for dear life. He was also listening to a dozen audiobooks a week, having the New York Times read aloud to him every afternoon, following the exploits of Philadelphia sports teams, and keeping up with his children and grandchildren.

And, once a week, he talked to me.

It wasn’t always easy. Some weeks he was tired. Some weeks he was in pain or other distress. And I think a good bit of the time I genuinely annoyed him. There were so many things in his past that he just didn’t want to talk about anymore. He mostly cared about his current work. And the fact that he had current work was probably keeping him alive.

He made it clear from the first day we met that there would be no “Tuesdays with Morrie” moments. Mental health professionals who overspeculated, offered armchair advice, and spoke in generalities irked him. He viewed himself as a mental health scientist whose job was to come up with theories about behavior, operationalize treatments based on the theories, and then prove the treatments worked. He was sure that what he was currently working on would not be proven before he was gone. So he was less interested in being understood than just having someone appreciate that he was still thinking, still growing, still living. If I posed an intriguing query that he knew he wouldn’t have time to explore and answer, he seemed very satisfied to stare straight ahead and say, “That’s a good question.”

He especially didn’t want to talk about death. Once, when I tried to follow up on a reference he had made to dying, he waved me off, yelling, “Silence! Silence!” He later apologized for the tone, but not the message.

As he grew weaker, he still somehow summoned the strength to lecture me not only about what I asked him but also the way I asked. On our last morning together, he accused me of trying to put him into an “interviewer’s trap” of giving him multiple choices.

“You have to learn to ask questions that require a yes or no answer,” he explained. I promised I would try. Then he said he needed some applesauce.

His hospice aide went and got it, and I assumed he was done with me for the day. I stepped out into the hall of his Rittenhouse Square apartment, and chatted briefly with his wife, retired Pennsylvania Superior Court judge Phyllis Beck, who in her 90s was still in good health. She said she didn’t know how much longer he had, but also admitted she had gone to sleep every night for the past nine months not sure he would be there when she woke up in the morning.

In the hallway, I could hear Tim’s raspy voice, as he was talking to his aide about the temperature of his applesauce, which was too cold. And then he called out to me.

“Steve … Steve!” I hurried back in.

“I think I can take one more question.”

Two days later, he was gone.

The first time I met Tim Beck, he tiptoed toward me in his wheelchair, his green socks padding along the polished granite floor until he met me halfway. He raised his right hand—his long, misshapen fingers curled in a sort of cubist fist—and waited for me to bump it. This was back in the late summer of 2019, when people still shook hands. But Beck was, as usual, ahead of his time. He had just turned 98, his vision was fading, and he could barely walk. But he was fiercely protective of both what remained of his health and of his beautiful mind. There was much left to do. So, no handshaking and risking infection.

In the 1950s and 1960s, as a young neurologically trained psychiatrist, he dared to suggest that Freud’s ideas should be tested using a relatively new technique—randomized clinical trials. In doing so, he completely undermined a key psychoanalytic idea about how depression is formed in the mind. After destroying enough of the foundation of Freudian analysis to suggest there needed to be something more practical and provable to take its place, he began creating a replacement, melding the shorter-term, generally face-to-face “supportive therapy” (which he had learned during his Army medical service during the Korean War) and early “behavior therapy” into a new form of treatment. He called it “cognitive behavioral therapy” or CBT. Instead of exploring the endlessly deep reasons why patients felt a certain way, his therapy was built on identifying “automatic negative thoughts” that led patients to “catastrophize” their reality, undermining their ability to function. His therapy offered practical ways to combat, displace, reality-check, or otherwise de-catastrophize these negative thoughts without belaboring them.

Beck then decided to do something even more radical. He tested the new therapy in a randomized clinical trial to make sure that it actually worked. In so doing, he almost single-handedly forced mental health care to confront the need to be what we now call “evidence-based.”

Beck’s ideas about therapy were developed before there were many useful psychiatric drugs. So CBT was designed to be used either with or in place of medication, as a first-line treatment for mood, anxiety, and personality disorders. The new therapy not only radically changed psychiatry, but it led directly to the development of modern clinical psychology. Before CBT, most psychologists trained for careers doing testing and lab work, not therapy. Once his treatment models were complete and had been tried on several different illnesses, he went on to train generation after generation of psychiatrists and psychologists who were able to offer short-term, non-psychoanalytic, directed therapy.

Almost 60 years after his original innovations, the gauntlet Beck threw down still challenges every new mental health patient, clinician, government regulator, and health insurer. The debate over whether a patient should get therapy, medication, both, or neither—a debate that remains scientific, economic, philosophical, and even religious when it should just be medical—is played out, as if anew, every time someone thinks they are depressed, manic, anxious, or haunted enough by trauma that they might need care.

More than most people realize, that debate has been informed by Tim Beck.

I remember first hearing about Beck and cognitive therapy in 1976, when I was a sophomore at Penn with a single in the Quad, and the RA in the next dorm over—where my girlfriend lived—was one of Beck’s post-docs, just beginning to spread the word. (I didn’t make the connection at the time, but the youngest of Beck’s four kids, his daughter, Alice Beck Dubow C’81 L’84—now a Superior Court judge like her mom—was two classes behind me at the Daily Pennsylvanian.) By the time I started covering mental health for Philadelphia magazine in the 1980s, Beck was a local hero and a top-selling author but not quite a national household name. I would see him at Phillymag Top Doctors parties in his trademark bowties, but never knew him. When I got some therapy myself, it didn’t register how his work had influenced it; and when I interviewed psychoanalytically trained psychiatrists who decried the rise of shorter-term, directed therapies, I didn’t understand they were hating on Beck.

Decades later, I was working with mental health advocate Congressman Patrick Kennedy on a book and the creation of the Kennedy Forum mental health initiative. We were trying to decide who should get its first lifetime achievement award at the JFK Library in Boston, on the 50th anniversary of the landmark Community Mental Health Act. I lobbied for Beck, who was at that time 92. I was there while he was celebrated by Patrick and then–Vice President Joe Biden, but we never really met or talked.

When I arrived at his apartment that first day in August of 2019, our sandwiches were at the ready. His tuna on wheat was already unwrapped so he could feel his way to it and eat without help; my turkey and cheese with mustard on wheat was still wrapped, along with a small bag of pickles. As I tried to start a conversation on what I thought we should discuss, he waved me off with his free hand.

“Here’s what I want to talk about first,” he said, firmly. Since he was pushing 100 and had, by his own admission, just a couple of good hours on his best days, I understood why he wanted to control the conversation. But when I later spoke to some of his associates, they said this had nothing to do with his age. Tim Beck had always been this way. He learned very young that time was limited, and he either controlled it or it would control him.

So, we talked about what he wanted to talk about. And that’s what we did for the next two and a half years. We discussed the possibility of me writing a biography of him, but at our first meeting he also said he had been working with another biographer, on and off, for the past 12 years. He said he hadn’t heard from her in a long time and had no idea if he, or she, would live long enough to see the book finished. There had also been a more academic biography of him published back in 1993, when he was 72 and presumed almost ready to retire. But while we never formalized what we were doing, he sometimes liked to refer to me as “my biographer.”

I came to his apartment almost every week for lunch and a taped conversation.

While he mostly wanted to talk about his recent work, sometimes he would forget and wander into his past, growing up in a close-knit Jewish community in Providence, Rhode Island, in a middle-class household with a mother who suffered from depression after losing a daughter, his older sister, to the flu epidemic in 1919. Beck was born two years later, and almost died of a blood infection after breaking his arm when he was seven, causing him to be held back a grade. So mental health, and fear for his health in general, loomed over him from the start. His hypochondriac tendencies were well earned. So were the automatic negative thoughts he later used to inform cognitive therapy. Beck reported that he often saw himself as a “loser” growing up, the youngest of three boys.

Just a few weeks into our work, I saw him in the outside world. His training facility—the Beck Institute for Cognitive Behavioral Therapy on City Line Avenue, now run by his psychologist daughter Judith Beck CW’75 Gr’82—held a 25th anniversary bash at the Masonic Hall across from Philadelphia City Hall. He attended, wearing his trademark bright bow tie, which he told me was always a clip-on, because he couldn’t be bothered to tie a tie. And he was strong enough that evening to be wheeled up on stage and say a few words. Judith introduced him as “the Original Disruptor in the treatment of mental health.” Friends, colleagues, and mentees came from all around the world, believing this might be the last time they would see Tim Beck in person.

At the end of the evening, I stood outside the Masonic Lodge and watched the painstaking process of Tim’s family and aides trying to roll him in his wheelchair, slowly and carefully, step-by-step, to a waiting car.

Not long after this, he became ill—with eye and stomach pains—and in early February of 2020, we did our first interview at his bedside. He slept in a hospital bed in his office; his wife slept in the bedroom down the hall.

After a couple of weeks, he got sicker and had to spend a few days in the hospital. And when he returned, his son Roy Beck M’77, a physician, decided that he shouldn’t be seeing any guests at all. There was some new virus he was hearing about that might cause problems. On March 6, we did our first weekly interview by telephone. I didn’t know if I would ever see him in person again. In our interviews and email correspondence, he kept telling me he didn’t think he had much longer.

He started dictating more, to himself and to me, largely through one of his assistants, Victoria Wyeth, granddaughter of the late painter Andrew Wyeth, to whom Beck was partly boss and partly brilliant grandfather replacement; a lecturer on her family’s work, Victoria also had a master’s in psychology and had also done therapy work at Norristown State Hospital.

He also pushed me to speak with his closest colleagues and most significant proteges—although not his wife, who had a policy of never speaking to the press about his work. I came to see better how his life was organized. Besides his family, his two assistants, and his aides and housekeeper, his main lifeline was Penn psychology professor Rob DeRubeis—his last tennis partner before Beck started losing his sight—with whom he spent an hour or two every Sunday, mostly talking about sports and news. He stayed in almost-daily touch with his daughter Judith about the business of their CBT training institute, and often interacted with its CT-R experts, Paul Grant G’93 Gr’05 and Ellen Inverso, with whom he was finishing the first textbook on the treatment.

Once a month he met for lunch with three friends: two academic pals from Penn—Howard Hurtig GM’73 and Gino Segre, emeritus professors of neurology and physics, respectively—and another from Drexel, psychologist, attorney, and former APA president Donald Bersoff. (When their meeting switched to Zoom, he invited me to listen in.) He periodically talked to his former student and fellow Penn mental health star, positive psychology founder Martin Seligman Gr’67, the Zellerbach Family Professor of Psychology. And he had a friend from childhood, and another one from med school, who reached out by phone or text nearly every day, just to say hi and send their love.

Because COVID prevented him from visiting in person with people, which was a lot of work for him, he actually had more mental energy in isolation. In his daily dictations, he dug deeper into theories of personality and how schizophrenia worked structurally. I would be hard-pressed to explain this (as was he), but one thing he came back to repeatedly was the observation that had been made by him and his staff while working with the sickest, long-hospitalized patients, that in certain circumstances they seemed to be able to “switch” to what he called a different “mode” and suddenly be more present and less symptomatic. He was the only mental health practitioner I ever met who described anything from One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, the most anti-psychiatry movie ever, in positive terms. He said the scene where the patients escape in a school bus, go fishing, and seem to temporarily shed their symptomatology was something he and his therapists had seen, in smaller bursts. One of the cornerstones of their developing CT-R therapy is to find each patient a “sweet spot” where they would be distracted even from their inner voices by something they liked to do, which gave them pleasure and reward.

He would also throw out email challenges to his entire staff to discuss some enormously large subject: on March 17, 2020, it was “Homogeneity of the Brain and Mind”; the next day brought “constructing a monistic or unified theory of personality.”

But then a week later he was in the hospital again, with an esophageal spasm, and he emailed me: “I do not believe I am likely to be around very much longer.”

I told him I would remain optimistic and asked for his Hebrew name so I could say the Jewish prayer for healing for him. Six minutes later, he emailed the name back to me from his iPhone. A week later he was home, feeling better, and we resumed our calls. He started emailing and dictating again and would occasionally send me copies of his correspondence. An Iranian psychologist sent him a series of questions to answer by email. One of the Q&As was so typically Beck it made me do a spit-take.

Q: Human suffering has not diminished and increased in spite of extraordinary human progress. Why [does] human suffering continue to grow despite the advancement of psychology and its spread among the people, and what should be done?

Beck: I am not sure that human suffering has increased. I would like to see the hard statistics on that.

During this time, both the American Psychiatric Association and the American Psychological Association were asking Beck to prepare career-assessing talks for their now-virtual conventions. It reminded me of the odd position he had put himself in. He had created cognitive therapy to revolutionize his own medical field, psychiatry, and make it work better. But instead he had helped create clinical psychology, which had become the main competitor of psychiatry. Some of this had to do with the role of psychiatric medication, which psychiatrists can prescribe but psychologists cannot. But it also involved two guilds of brain disease that share many treatments but have never figured out how to get along. Beck never got involved in all this—he had full prescribing capabilities but was primarily interested in researching how targeted psychotherapy could work instead of medicine, or despite medicine. He wasn’t against drugs, but he talked about them like a psychologist, as something that we over-relied on, while failing to appreciate psychotherapy.

These talks were in honor of his approaching 99th birthday on June 18, 2020. There were also several big birthday Zooms—a family Zoom (which Tim couldn’t convince the family to let me watch), a Zoom with his monthly friend group, and then a big Zoom of his colleagues and mentees from around the world.

Though he wasn’t feeling well in the preceding week, Beck survived his birthday Zooms, and did a lot of dictating through the fall. In December, the book he coauthored on his “radical new” approach to cognitive therapy, CT-R, was published to little fanfare. He didn’t seem to care. He still felt that cognitive therapy itself hadn’t been as widely accepted as it should be. His protege in England, David Clark, had been instrumental in making sure it was available through the National Health Service and had made the treatment a cornerstone of the Royal Family’s mental health efforts. The same thing had happened in Japan, where his former student Yutaka Ono had treated the Crown Princess Masako, inspiring many to try the same treatment. In America, Beck felt cognitive therapy had become so much a part of the language of mental health that he wasn’t sure many people really knew what quality CBT was and where to get it. He was also wrestling with whether or not CT-R—which included more positive psychology and mindfulness and less reliance on exploring automatic negative thoughts, because the patients were so much less functional to start with—would ever inform a new hybrid version of CBT for all patients.

In January 2021, soon after the first COVID vaccines became available, Beck’s office informed me that he was in the hospital with hip pain. Then came the diagnosis of a broken hip; he hadn’t fallen, but simply moving him around in his bed and occasionally in and out of it had been too much. He had surgery to stop the pain, and then spent a horrible week at a local hospital, where he kept insisting nobody was paying attention to him because of his age. All of his family and friends who were physicians later agreed he had been correct.

When he got home, he was obsessed with the way he had been treated, especially since several times he had been allowed to get dangerously dehydrated because the nurses failed to respond to his calls, and he had developed a bedsore from not being moved enough. (Hospitals were stretched thin by COVID admissions.) He wanted help complaining to someone in authority but his family and friends finally convinced him there were better things to do with his time. So, he got back to work.

His goal now seemed to be to make it to 100, to keep developing his theoretical work, and to launch a final clinical study testing the efficacy of CT-R. He and his colleagues had decided that, instead of studying the inpatients with whom they had developed the therapy, they wanted to test it on outpatients living with psychotic diseases, to see if it could be proven effective as an additional therapy to their medications. They started organizing to have the study be done at the Hall Mercer Community Mental Health Center in Pennsylvania Hospital, where American mental health care had been born in the late 1700s.

He kept dictating: for several days he explored “self-stigma,” which was not the stigma that came from the attitudes of others, but from within the individual. Sometimes he would run out of steam while dictating and simply fall asleep, leaving his assistant to decide whether or not to wake him, or just quietly hang up. Although he still listened to a lot of books on tape, he now preferred more and more to be read to—because of his thirst for knowledge but also, frankly, for company. Victoria Wyeth had taken to calling him every afternoon and reading the New York Times aloud. Once they got done with the Times, if he was still awake, he would ask her to keep reading—anything.

He was fierce in his desire to learn and continue to contribute something every day. Whenever my wife and I would watch another show on Netflix, I felt slightly embarrassed knowing what Beck would have done with the time—and the ability to see.

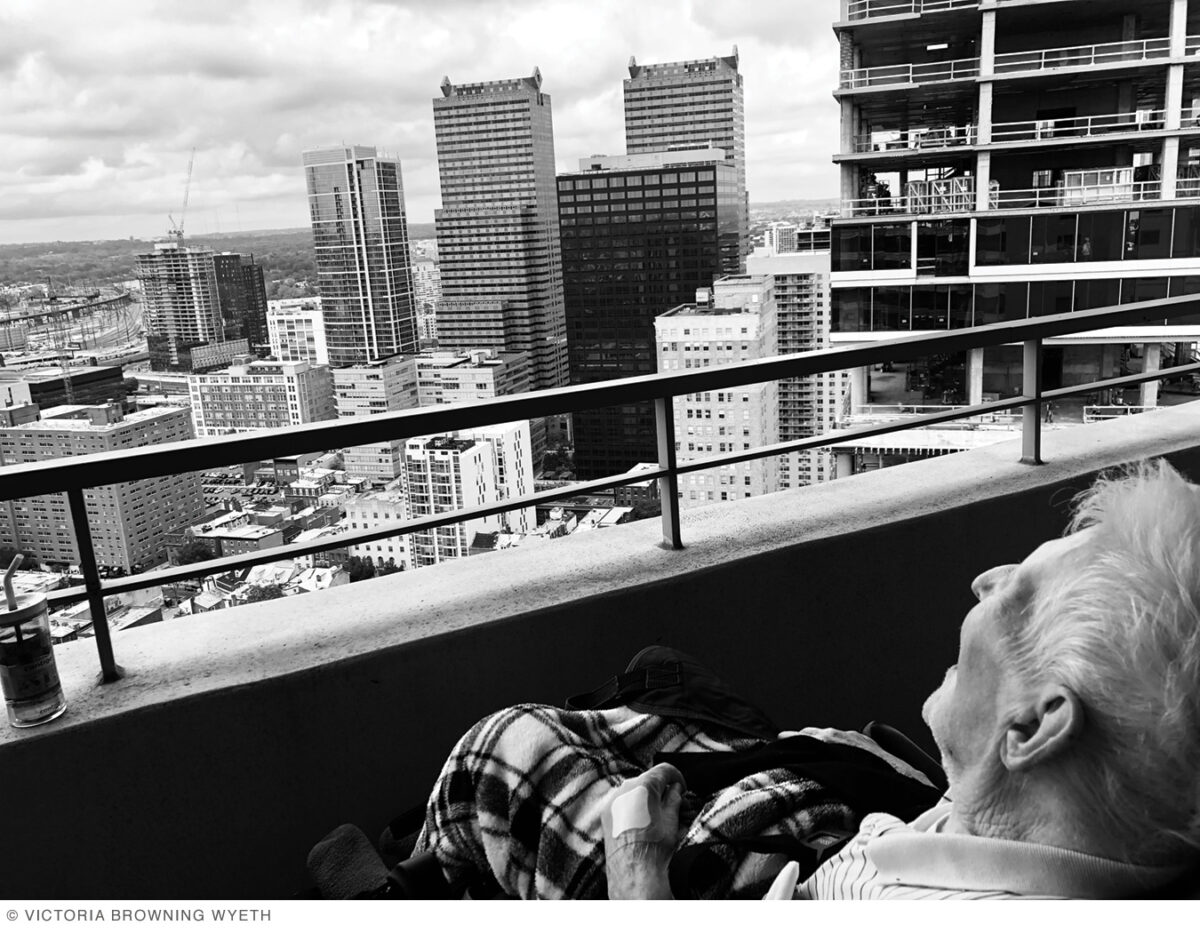

By spring 2021, many people had been vaccinated, and were starting to actually interact in-person again. On a sunny day late in May, Victoria Wyeth called and said she and his longtime aide Marina were going to bust Beck out of his apartment for the first time in well over a year (except for his hospital stay) and take him over to Rittenhouse Square. She asked if I wanted to come by. I hadn’t spoken to him in person in 15 months, so of course I went over. He was in his wheelchair, but the back of it was laying almost flat, so he looked more like he was on a stretcher; this was because he hadn’t fully recovered from the bedsore that had developed months before. He was wearing a tennis shirt and a hat pulled down over his eyes. Two friends had joined him as well. They were all talking to him, but he wasn’t saying much.

I was happy and surprised to see him; it had been so long, and he’d said so many times he wasn’t going to make it. We chatted a bit, but he was already tired from the effort of getting out of bed and being wheeled to the park, so I didn’t want to push him. So at some point I just stopped, took his hand and, without thinking, bent down and gave him a little peck on the forehead.

He had six weeks until his hundredth birthday. During that time, his pulse-oxygen level crashed (not from COVID), and the family decided to start him on hospice care. Word went out across the Beck-osphere, and emails began pouring in from proteges wanting to thank him one more time. He immediately started feeling a little better—well enough to begin challenging the decision to change his status. In fact, he disliked the word “hospice” so much that when he talked about changing his status back, he pretended not to remember the actual word “hospice.”

By this time, we were meeting in person again, but only for 15 or 20 minutes—and sometimes he barely spoke. Once, when he was really weak and I had just returned from the Jersey Shore—where my family has a house on Long Beach Island as the Becks once did—I came by just to drop him off some fresh Jersey blueberries, which he loved.

Miraculously, he made it through his birthday, although he started fading in the middle of the big, international Zoom party that had been prepared for him, and he had signed off before it ended. After the birthday weekend, he seemed a bit stronger. Our weekly talks began lasting an hour again, and he told me some stories I’d never heard before.

One day in August he said he had been thinking a lot about delusions, because one of his researchers had dug up a 1952 paper he had written about them, concerning the case of a patient who was obsessed with being followed, which Beck had determined was based on his father’s experience in the FBI. He explained that therapists were often fascinated with the details of patient’s delusions, and their possible basis in the patient’s past.

I asked him if discovering the factual root of a delusion helped the patient.

“No, insight does not help,” he said, and then he paused for a second. “Living a rich full life … that helps.”

Tim Beck’s rich full life continued for another two months, but they were more challenging. One Saturday I arrived and a number of family members were there. Judith was in Beck’s bedroom trying to calm him down. He had had a nightmare that he was trying to commit suicide, and even though he had been awake for a few hours, he couldn’t shake it. He said that even though it was a dream, it was the first time in his entire life that he actually understood what feeling suicidal was like. He was upset, but also fascinated.

Father and daughter suddenly started talking about it like two therapists.

“Yeah, so it sounds like you’ve described the attentional fixation that happens when people feel suicidal,” Judith said.

“That’s right!” he said, “So it was valuable …”

“… to go through that experience.”

“Right!”

“I know, isn’t that interesting you can understand some things at an intellectual level but until you actually have the experience yourself it doesn’t really hit home.”

“Yes, I had the experience just for a few minutes … but anyhow, so much for that …”

I asked him whether being suicidal felt different than he had imagined.

“All of the plusses became insignificant and the only thing I wanted was to get over the bad feeling, and in this particular case it was a bad feeling that I did not feel I could tolerate.”

“It’s a little different from people who have suicidal ideation for more than a few minutes,” Judith explained. “Because I think what happened was you had the suicidal ideation, you felt really down, your attention got really fixed. Then you got very anxious. Many suicidal people don’t get anxious. But you were anxious because you thought you couldn’t tolerate this feeling and you were afraid it wouldn’t go away. And then something switched, you were able to switch away your attention either from how bad you were feeling, or you realized you could tolerate the feeling and your mood changed.”

Then the conversation effortlessly shifted to all the visiting kids and grandkids and what they were doing that afternoon, and Judith left. We started talking about something else. But then, 20 minutes later, in the middle of the conversation, he said, “This takes me back to my suicidal thought.”

I had learned by this time never to actually ask a follow-up question about something this personal, and just waited. He started telling me about a conversation he had the day before with a hospice nurse. He told her he thought he was “overqualified for hospice, and she agreed with me. And then I thought I’m gonna get better. I’m gonna get more better before I pass away, which may be in a year from now or even two years from now.”

Then he started thinking about the way he might die. There would be either “the involuntary way, if I just had a heart attack,” he said, “or the voluntary way, which would be suicide. And somehow those two things made the voluntary more acceptable.”

He didn’t know why, exactly.

“If I had time, if I had the energy, I could figure it out.”

He then immediately started talking about one of his recent interests, attentional fixations and how they manifest in mental health. “I figure I’m gonna live two years,” he said, “so I’m hot for showing how attentional fixation occurs across the board.”

In reality, the hospice nurses had already told the family they expected Tim Beck would live only a few more months. His brain was still working—sometimes amazingly well—but his other organs were starting to shut down. We continued to meet weekly, our conversations a combination of Tim speculating on whether or not he was dying, and then his latest psychological fascination. He was still energized by big ideas, even though he admitted he was no longer sure that he, or someone else, hadn’t thought of them before. “I try not to presume,” he said, “that I just discovered America.”

Before I left each week, he told me he appreciated me coming and putting up with his irritability, and then offered some version of “we’ve come to the end of this.” But then the next Saturday, when I texted in the morning to see if I could come visit, he or one of his assistants always texted back that it was fine. Sometimes when I got there it wasn’t clear he would, or could, really talk to me. Once he whispered that he only had the strength to answer yes or no questions with a thumbs-up or thumbs-down. When I told him I just couldn’t think of any yes or no questions—psychology is not really such a yes or no field, it’s very “maybe” or “let me explain”—he would somehow summon the energy to talk for 15 or 20 minutes.

His whole personal life and career was, at some level, based on the concept of the automatic negative thoughts we bring to any situation, and how quickly we can remind ourselves that they may or may not be true: they may be our fears, and not facts. Every time I saw him near the end, I watched him self-correct against his negative thoughts, so he could tell me more of his ideas. It could be hard to watch sometimes, especially as his body got smaller and more curled, his features more angular, like an amazing and shocking German Expressionist painting.

The last time I saw him was no different. After he called me back from the hallway, saying he could answer one more question, we talked for another 10 minutes. We got into a discussion about control, and whether people who try to control others are really just trying to control themselves, or to avoid controlling themselves. He said it could be, adding that he didn’t want to make a generalization, but much of what people did was in the belief it would increase their self-esteem.

We finished, we said our goodbyes—which this time really did feel like goodbye—and I told him it was an honor to be able to spend all this time with him. As I packed up my computer, I noted that it was Halloween. I asked him if he remembered anything he had ever dressed up as for trick-or-treating. Did he maybe dress as a psychiatrist?

His last word to me, with whatever strength he had left to grin, was “no.”

Stephen Fried C’79 is an award-winning journalist and bestselling author who teaches at Penn and Columbia and writes on mental health and many other subjects. His biography of Philadelphia physician and founding father Benjamin Rush was excerpted in the Nov|Dec 2018 Gazette.

What an amazing man! Prayers, love and blessings for his family and friends. Aaron will most certainly be remembered! X