Class of ’01 | For too many years of his life, audacious ambitions, combined with an often-unhealthy obsession with arguing, stunted the psychic growth of Douglas Robbins L’01.

Yet it was precisely those two qualities that spawned a work that has exorcised many of the demons of his past while giving him a fresh outlook for the future: an independent documentary film called Debate Team (www.debateteamdocumentary.com), which Robbins produced, directed, and edited with little more than a vague knowledge of filmmaking and a few maxed-out credit cards.

“I was unemployed and my vision for how my career would turn out had crashed and burned,” admits Robbins, 38, who had been laid off from his San Francisco law firm in 2003, shortly before he started work on Debate Team.

“The only real risk is the cash,” he says. “But you tell yourself, ‘For $10,000, I can live my dream or buy a used car. What do you want to do here?’”

The answer was simple. He would make a film about something that was close to his heart: college debate tournaments and all the bizarre quirks associated with them.

But to start the project, Robbins had to lie to himself, both about the scope of the film and his chances for success. He told himself that the film would be short and not very time-consuming. And if everything went right, he reasoned, his documentary could be a critical success and earn an Academy Award nomination, the same way Spellbound had a couple of years earlier.

“Realistically, your chances of winning an Academy Award are similar to your chances of winning the lottery,” Robbins says. “But emotionally, you think, someone has to get an Academy Award nomination. The fantasy keeps you moving at all times.”

Nine years earlier, Robbins had a similar fantasy. After graduating from the University of California-Berkeley—where he participated on the debate team—he spent the next six years heeding the words of the late American writer and mythologist Joseph Campbell, “Follow your bliss.”

Robbins thought his own path to bliss would go something like this: Write a best-selling novel about debate. Go on Letterman. Be set for life.

“I never had an experience with rejection,” he says. “I never thought it would fail.”

But it did. His novel wasn’t published. The six years spent writing all day and then working odd night jobs to make ends meet seemed like a complete waste. Worse, he started to question what he was supposed to do with his life.

“Maybe that wasn’t my bliss,” he says. “Maybe I should have been growing a business. Maybe I should have joined the Peace Corps. Maybe I should have found true love and had kids. It begins to shake your foundation.”

Penn Law gave him a second life. In the summer of ’98, Robbins left his family, friends, and life as a struggling novelist back on the West Coast. He used his writing skills and debate acumen to make the Law Review. And when he graduated, he got a high-paying job at a prestigious firm back west.

But he never could shake that creative itch. More to the point, he still needed to bury the demons that had haunted him ever since his novel was rejected.

“He’s a very targeted man,” says Robbins’ sister, Erin, an associate producer on Debate Team. “When he sees something he wants to do, he just does it.”

When Robbins got laid off in 2003, it almost felt like a relief. He had hated some of the mundanities of his job. He felt like a cog, a glorified paralegal. And he didn’t even get a chance to do what he’s always done best: arguing.

Even as a kid, arguing came naturally to Robbins. Some of his earliest memories were of verbal clashes with his parents over how long he could stay out and play, or whether or not he could use a hammer. Long after those arguments had ended, he remembers returning to his room and retracing the contours of what was said to prove to himself, if nobody else, that he had won the debate.

In college, he earned the nickname Argument Man. It was also there that he fell in love with competitive debate tournaments, where real-world rules of politeness and etiquette are thrown out the window and the only thing that matters is the content of your argument. “I found the whole thing intoxicating,” he says.

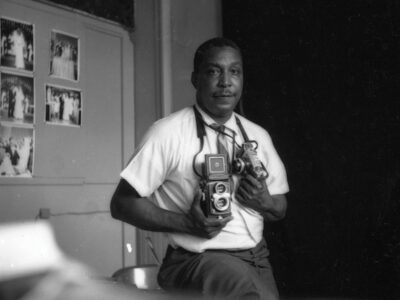

So when, all of a sudden, his days and nights became free, he decided to buy an expensive camera, learn Apple’s Final Cut Pro, go to a few debate tournaments with his best friend and co-producer, Joseph Walling, and then try to make a movie.

“We decided to do it first,” Robbins says, “and sort through the wreckage later.”

There was inevitably some wreckage along the way. For instance, Robbins and Walling had to lie about their insurance policy—they didn’t have one—to shoot their first tournament. And only later did they find out that much of their material was unusable because of audio or focus issues.

But after about three long years in post-production, Robbins finally had his film, which premiered late last year at the San Francisco International Documentary Film Festival and is currently available on DVD.

The funny thing about the end product is how much it changed from Robbins’ early vision. At first, he’d thought the film should be crafted in the mold of The Karate Kid, in which perseverance triumphs over adversity, the champion is bathed in glory, and everyone lives happily ever after. But soon he began to focus on some of the deeper—and spookier—parts of debate: how competitors are trained to talk at a pace that’s incomprehensible to most people, how the theme of planetary extinction surfaces in most debates, and how winning means so much to some debaters that they’d say they’d kill a puppy if it meant they wouldn’t lose.

Many of these themes resonated on a personal level with Argument Man, who was once asked by a girlfriend: “Do you want to be right or do you want to have friends?”

“There’s an underbelly to debate,” Robbins says. “It arguably over-encourages the concept of intellectual domination above other values. In the end, arguing is a good tool. But like any good tool, it can be overused and it can end up causing pain.”

These days, Robbins isn’t feeling the same kind of pain he felt when he was younger. Although his film failed to get any financial backing and was rejected from all of the elite film festivals, he is glad he produced an in-depth, semi-scathing portrait of an activity that has shaped his life in such a profound way.

His Oscar dreams may have long since vanished—his main goal now is just to break even on the project through online DVD sales—but that’s OK with him.

“I’m never going to look back and say I didn’t even give it a shot,” says Robbins, who now works at a small law firm where, he says, he can actually practice the law. He also recently founded the Media Law Group, which he hopes will help other independent filmmakers understand the legalities of making their own film.

“I’ll never have those regrets,” he continues. “Now I’m dating a beautiful girl; I’m happy with what I’m doing; and I made a documentary that many people enjoy. At this point, I’m focusing on being happy with who I am and less obsessed with what the American culture thinks I should be.”

The tagline of Debate Team is “America loves a winner and will not tolerate a loser.”

Once, the director believed that.

—Dave Zeitlin C’03