How colleagues united to complete Harold Dibble’s final project in France.

Before his sudden and unexpected death in June 2018 [“Obituaries,” Nov|Dec 2018], Penn archaeologist Harold Dibble Hon’91 was planning a “dream project” at a site in Dordogne, France, where since 1976 he had been involved in digs in caves once occupied by Neandertals and where he had established warm relationships with French colleagues and the inhabitants of the nearby village of Carsac. Dibble and colleagues had devised a plan to collect and analyze the oldest sediment found in a cave known as Pech IV, which held the potential to yield more comprehensive and detailed information on Neandertal lifeways than possible by focusing primarily on objects alone.

Dibble managed to tell family and close friends and colleagues some of his final wishes—among them, to “finish the Pech project.” His longtime colleagues, many who had worked for decades with him in France—Dennis Sandgathe of Simon Frasier University, Paul Goldberg (University of Tübingen), Vera Aldeias Gr’12 (University of the Algarve), Deb Olszewski (Penn), Shannon McPherron Gr’94 (Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology), and Teresa Steele (University of California Davis)—came together to fulfill his request. This past summer I joined their crew, which included researchers from France, China, Germany, Ethiopia, Portugal, Canada, and the US.

Pech IV is set on a steep limestone ridge covered in oak forest on a hill that bears the Occitan name Pech de l’Azé—Hill of the Donkey. This donkey hill has four caves, three of which—Pech I, II and IV—contain Middle Paleolithic Neandertal occupations dating back as far as 180,000 years. Pech IV is especially rich, and its vertical face shows meters’-high strata of frequent Neandertal presence from some 100,000 to around 42,000 years ago. The first comprehensive excavation was by renowned French archaeologist François Bordes from 1970 to 1977; from 2000 to 2003, Dibble and Shannon McPherron led a second excavation, joined in 2001 by Goldberg and Sandgathe.

From the moment the team arrived in Carsac in July 2022, Harold’s absence was palpable everywhere. You could feel it in the local house he had rented since 2000, whose long backyard served as the dig camp next to a barn he had set up as a lab. His memory was alive in the village center at the hotel-restaurant run by the Delpeyrat family—Philippe and Aline and their children Aurelie and Sabastian—who had known Harold since 1976. And the village road named after his mentor, François Bordes, now sported a new street sign marking an intersecting cul-de-sac: Impasse Harold Dibble. His old friends had installed it in early 2021. When I saw it, I couldn’t help thinking that, were he alive, Harold would crack some dead-end joke, while also being touched by the act.

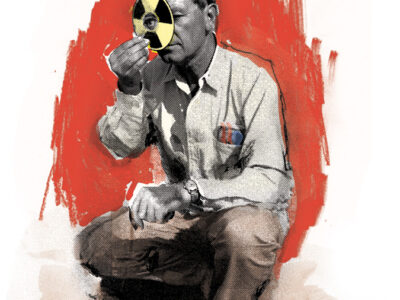

First as a graduate student in his courses, then as editor of Expedition magazine at the Penn Museum, and later as a writer reporting on his work for the Gazette [“On Hearths, Ancient and Modern,” Nov|Dec 2010] and in my book Café Neandertal, I witnessed how Harold dedicated his life to studying Neandertal and early modern human behavior. He was a world-renowned lithics specialist whose work and ideas influenced and often instigated debates—about what drove site formation, stone tool variability, early human fire use, burial practices, and more. Above all, he emphasized the need in archaeology for better methodologies that promoted scientific—standardized, consistent, methodical, replicable—approaches to research.

“He’s one of the few [non-French archaeologists] who actually understood the French way to do things and he critiqued it professionally,” Alexandre Steenhuyse Gr’07 told me one evening in Carsac, “but also, he cared about the connections between people. [It] was all about respect and I think he’s respected here for that.” Steenhuyse, one of Harold’s former doctoral students, had come down from Paris for the summer to join the 2022 dig. “And,” he added, “[Harold] was sincerely welcoming of any real challengers with generosity and kindness.”

Harold’s son Flint Dibble C’04, who is also an archaeologist, told me his father “had an amazing amount of empathy, and ability to listen, and the ability, therefore, with logic and emotion, to see to the crux of stuff.”

Harold first came to Carsac in 1976, having met Bordes the year before through Art Jelinek, an archaeologist at the University of Arizona, Tucson. Invited to join the dig at Pech IV, Harold pitched his tent with the rest of the crew in the Bordes’ orchard, which was near the village house the family was fixing up to use during summer dig seasons. The crew bathed at the river and took their meals up the hill in the village center at the Delpeyrat’s.

From the start, Harold got along well with François Bordes and with Bordes’ wife, Denise de Sonneville-Bordes, also a renowned archaeologist, who later helped him secure permission to dig at Combe-Capelle in the Dordogne, getting him more firmly established in French archaeology.

Their daughter Cécile Bordes, who was living abroad until the early 2000s, had not yet met Harold, but “I heard about [him] through my mother, and realized that he was becoming important [in] the modern progress of French prehistory with his innovative approach, partly based on my parents’ work and with the help of new technologies.”

When she returned to France, Harold invited Cécile and her mother to dinner, “for dégustation of his famous ‘Beans a la Dibble,’ in his amazing outdoor dining room,” she recalled, tongue-in-cheek, referring to the rough digs of the dig house’s backyard kitchen. It was the first of many evenings of conversation, aperitifs, and dinner at each other’s homes.

As a part of the 2000–2003 dig at Pech IV, Harold and McPherron’s team had worked on the earliest sediment layer, which they called Layer 8. It sat on bedrock and contained incredibly rich ancient fire and hearth activity. Applying different excavation techniques to investigate the layer’s features but finding nothing worked, they decided that rather than risk destroying it they would instead leave it for future researchers who could return with better methods.

In 2015, Harold and Dennis Sandgathe were back in Carsac, having recently finished digging at the nearby Neandertal site of La Ferrassie, and contemplating their next project. They circled back to Pech IV, with Paul Goldberg and Vera Aldeias joining the conversation. The four wondered about a different approach: What if, instead of focusing so much on objects—bones and lithics—they focused on sediment, and did a microscopic excavation instead of the usual macroscopic method? To that end they devised a vacuum system to collect all the sediment into sterile test tubes as they excavated each block. To systematically record the resulting data, McPherron rewrote mapping and cataloguing software he had originally written with Harold. With this new methodology, they had their new project; the future researchers of Pech IV Layer 8 turned out to be themselves.

They tested their method with Harold in 2017. In 2018, Harold died just as he was about to fly to France for what Flint said he called “a dream project.” His colleagues vowed to see it through.

In 2019 and 2021 (the pandemic halted work in 2020) they set up the lab, troubleshot the procedural design, and began excavating blocks. In 2022 they hoped to complete the job. When I walked into the lab, I witnessed an expertly choreographed excavation. At each sediment block, a dedicated excavator dug, collected, and recorded. Wearing nitrile gloves to minimize contaminants, the excavators scraped with dental tools and vacuumed the earth into attached vials, while colleagues sorted and stored the materials in freezers.

In the foreseeable future, these gathered sediments will be analyzed by molecular specialists to discern many things, from fire features that may illuminate Neandertal fire use, to DNA, phytoliths (plant remains), coprolites (fecal remains), and more, potentially recreating past environments and lifeways at a level never seen before.

They also continued another Bordes and Dibble tradition, having dinners prepared by the Delpeyrats, bringing large pots back to the dig house: hearty cassoulet, confit, roasts, salads, and other traditional southwestern French fare.

Once the last block was completed, the dig team had a final, harder, task: to remove all the equipment and materials from the dig house, to return it to the owners. The fact of so many endings—Harold, the team, France, Carsac—weighed heavily.

One evening at dinner, someone proposed walking to the other side of the village to where Rue François Bordes meets with the newly named Impasse Harold Dibble.

“Where the two greats intersect,” I said.

“Harold Dibble Dead End,” Dennis replied, channeling exactly the joke I was sure Harold would have lobbed had he been there.

I strolled that night down to the intersection. It was a comfort seeing his name on the sign, knowing that his nearly 42 years of life here would not be forgotten. Someone had left a stone tool atop the sign’s wall, a tradition that the Bordes’ students had begun on their own mentors’ tombstones in the cemetery on the other side of the village. I decided to follow the impasse to its end and discovered that instead of being a dead end, the road faded into a hillside and became a field—an ending of one thing and a beginning of something else. I could almost hear Harold laugh.

—Beebe Bahrami Gr’95