This National Park Service conservationist combats the impact of severe weather on fragile historic structures.

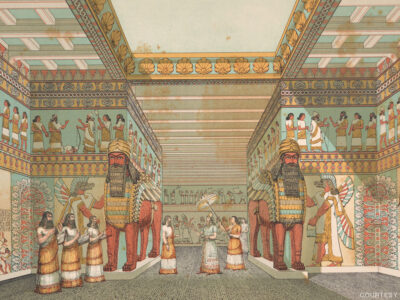

Fort Union in Watrous, New Mexico, is an important piece of the Southwest’s cultural heritage. It was the largest military fort in the region during the mid-19th century—holding 1,600 troops in 1861—and the site is now part of a 721-acre park that contains the remnants of numerous adobe buildings.

Fort Union is also what Lauren Meyer GFA’02 GFA’03 of the National Park Service (NPS) calls a “canary in the coal mine” for climate change.

As rising temperatures amplify storm intensity, wildfire risk, and other severe weather events, historic structures are uniquely vulnerable due to their aging, fragile materials. As the program manager of the NPS Intermountain Historic Preservation Services Program—which includes the History, Historic Structures, Cultural Landscapes, and Vanishing Treasures teams—climate change is a growing concern for Meyer.

“For a long time, park staff saw just small-scale degradation over time happening because of storm systems moving through,” she says. “But as we got into the mid-2000s, we started seeing stronger, more severe bursts of weather happening with no drying time in between storm events. And we started seeing more mass degradation.”

The program covers more than 87 parks in the region, located in both mountainous and desert environments. Based in Santa Fe, New Mexico, Meyer provides support and guidance to national parks for developing conservation strategies at cultural heritage sites, including the ruins of traditional stone masonry and adobe buildings.

Some sites, like Fort Union, are especially sensitive to changing weather conditions. Fort Union’s adobe compound was constructed using bricks made from dried mud mixed with straw and other organic materials. Although some adobe buildings have endured for hundreds of years, severe weather is weakening the historic earthen structures. Heavy, prolonged rains that cause flooding and don’t allow any time to dry out in between downpours, as well as strong winds, have destabilized both freestanding walls and multi-wall systems, she explains. The Fort Union site is also situated in an area prone to wildfires.

Research on minimizing the effect of climate change on aging building materials has lagged behind studies focused on protecting nature. That’s because harm to the environment from flooding, droughts, and wildfires is more obvious than climate-related damage to the remains of historic buildings, many of which already register as ruins, according to Meyer. Complicating matters is that the adobe materials require constant maintenance to slow degradation. At Fort Union, for example, conservation of the site’s 200,000 square feet of ruins includes the ongoing reinforcement of deteriorating walls.

Then there’s the sheer number of NPS cultural heritage sites in the region, many of which have value to the communities in their midst. “We can’t keep up with the amount of work that needs to be done to be able to maintain these resources in a condition that allows them to withstand the unpredictable environmental changes that are happening,” she says.

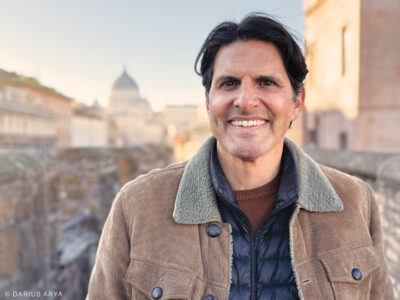

Meyer, who grew up in New York, earned a master’s degree in historic preservation as well as an advanced certificate in architectural conservation and site management from Penn. She became interested in historic preservation while doing archaeological fieldwork up and down the East Coast. “I’ve always been interested in history, culture, community, and material culture, and trying to understand how people lived,” Meyer says. “So, historic preservation is just a natural extension of archaeology.”

While at Penn, Meyer spent a summer working on the conservation of a sprawling cliff dwelling at Mesa Verde National Park in Mancos, Colorado, known as the Cliff Palace, with her mentor Frank G. Matero, the chair of the department of historic preservation at the Weitzman School of Design [“The Future of Our Past,” Jul|Aug 2009].

In their free time, they visited former students of Matero’s, who were scattered around the Southwest doing preservation internships and field work. By the end of the summer, Meyer received a job offer to be a field technician/architectural conservator at the Bandelier National Monument in Los Alamos, New Mexico, where pueblo dwellings dot the landscape’s mesas and canyons. “Literally two days after I got my degree, I got in the car and drove to New Mexico,” she says.

In 2012, as the program director of the Vanishing Treasures Program, Meyer collaborated with Matero and others at Penn, as well as additional partners, to create a rapid assessment survey on the effects of climate change at cultural heritage ruins in the Intermountain Region. The pilot program created a framework for identifying and monitoring site vulnerabilities at Fort Union. Researchers compiled existing data on climate change in the Southwest, identified the climate forces that are most destructive to man-made structures, and developed climate projections for the region. The survey has since been expanded to other cultural heritage sites within the NPS.

The rapid assessment survey not only supports maintenance, stabilization, and monitoring decisions, it has helped spotlight and prioritize the need to protect cultural heritage resources from climate change. In fact, the initiative has caught the attention of specialists who previously focused solely on natural resource conservation and are now participating in cultural heritage preservation projects, says Meyer.

“Prioritization is a huge thing,” she explains. “Anything that we can do to help us better understand conditions, to help us prioritize and to address those things that are most at risk first is going to move us along in a more positive direction.”

—Samantha Drake CGS’06