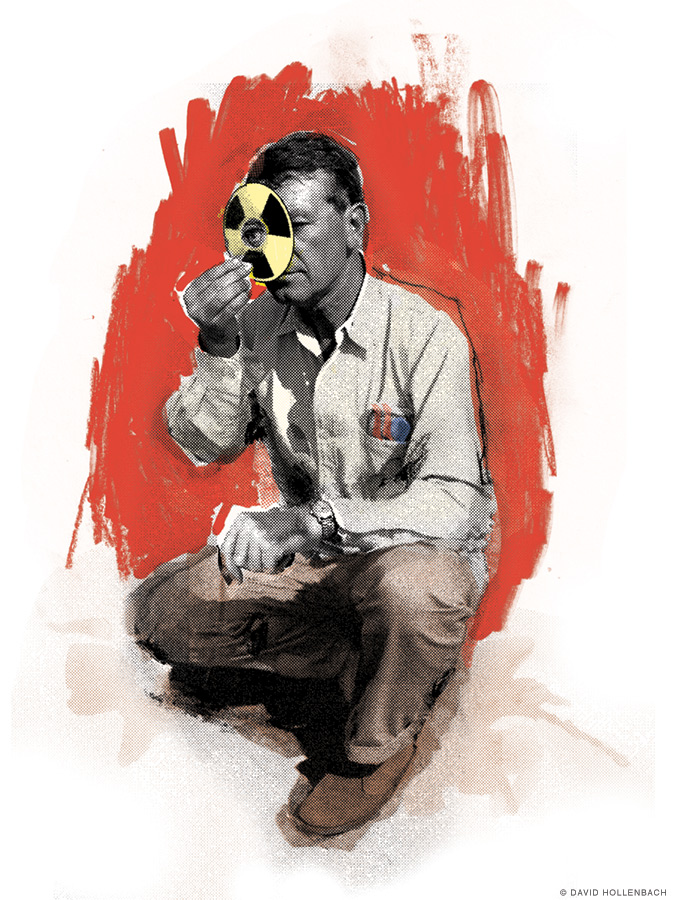

“There’s a lot of story to tell” about the longtime Penn Museum director.

“It sounds like Rainey”—that would be Froelich Rainey, director of the Penn Museum from 1947 to 1977—“was Indiana Jones,” suggested Thomas J. Shattuck, global order program manager at Perry World House, while moderating “Going Nuclear: Science, Diplomacy, and Defense,” a panel discussion on the legacy of Cold War science programs like Atoms for Peace.

The comment was prompted by remarks made by Richard D. Green University Professor Lynn Meskell—a PIK Professor with appointments in anthropology and historic preservation—on Rainey’s place within what she called the “military-industrial-academic complex,” as both a pioneer in incorporating new technologies into archaeology and sometime government agent and advisor.

Of the Indiana Jones comparison, “I obviously did not know him personally,” Meskell said. “He was very charming, very good on television. He had many, many international projects; he had worked for the State Department; he had been in the Second World War; he had been in Berlin. There’s a lot of story to tell there.”

Here are more remarks from Meskell—who came to Penn “with the pandemic” and, “because of field work restrictions,” spent time exploring the Penn Museum archives at the start of her tenure. (The entire panel can also be viewed on Perry World House’s YouTube page). —JP

“Rainey had these incredible international connections, but also believed that nuclear science was integral to the development of archaeology, and in fact it has been. He was on the committee with [1960 Nobel Prize winner for the development of radiocarbon dating in 1949] Willard Libby who decided which materials were going to be tested for the first carbon 14 dating experiments. He worked with governments, with the CIA, the State Department, but he also worked with scientists that were trying to develop a whole suite of new atomic applications—and that is still with us in archaeology. In our discipline, these are the techniques that help us locate, to prospect for archaeological materials subsurface. …

He was using or trying to use everything from U2 spy planes to submarines—geo-prospecting, radar, just a number of sonic devices. All of these things were coming out of what we call the military-industrial and now -academic complex. So you might not think that archaeology is one of the disciplines that would be directly linked to atomic research, but we were one of the really best beneficiaries. … And then you get into all of the international field work that also includes intelligence gathering, espionage, foreign diplomacy. Archaeologists are very good at that sort of work. …

[Rainey] started as an archaeologist in the 1930s in Alaska, and he thought Alaska was the sort of linchpin particularly in terms of the Cold War, and he thought that cultural exchanges—bringing students to the US, professors to work on archaeological questions, and for American scholars based at the museum to go to Russia—was a way of developing a sort of diplomacy that would actually be a better strategy than any nuclear deterrent. He was advising [Henry] Kissinger, if you can believe it—I mean, an archaeologist advising Kissinger is interesting in itself—through the Foreign Policy Research Institute, which is still going, based in Philadelphia …

So his Russian engagement was a key part of his career, but he launched projects all over the world. He was museum director for about 30 years. He had some spying missions, and archaeological collaborations in Iran, Afghanistan, Libya, where he was definitely doing espionage work. But one of the most interesting field cases I think was going to Italy—and I hadn’t realized how important Italy was immediately following the Second World War. So he got in with some people that had, again, physics [and] geo-prospecting training [like Italian engineer and industrialist] Carlo Lerici. And remember that so many nuclear scientists had come from Italy—think of Enrico Fermi—so those guys were ahead of the game, and I think the US was very nervous about European scientists.

So Rainey was the perfect person to do this, and a lot of money was given to him to have collaborations in the field, finding tombs, Etruscan painted tombs, for example, buried classical cities in the site of Sybaris—to test out the moon drill [developed for the Apollo missions] and all of these incredible gadgets that were themselves the product of this military-industrial-academic complex that were using Navy technology, Silicon Valley technology. And this is in the ’50s and ’60s, so there’s this incredible crossover.

And it’s not just a one-way application of archaeologists borrowing military or lunar tech but in fact the military coming back. For example, [Rainey] went on television to talk about some of his discoveries and then the army reaches out and says, ‘We’d like to use some of your subsurface gadgetry for our own purposes in Vietnam.’ So in fact, it’s a two-way street. Archaeologists are not usually thought of in those very inventive terms, but in terms of instrumentation, Penn was really cutting edge.”