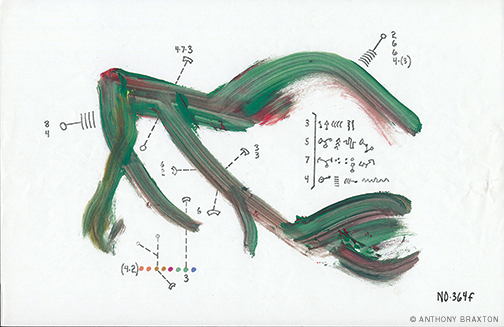

Falling River Music (364f) by Anthony Braxton, 2004-present.

Shortly after The Freedom Principle opened at the ICA in September, a number of musicians connected with the outfit that’s at the heart of the exhibition—the Chicago-based Association for the Advancement of Creative Music (AACM)—came to see it.

“They remarked in quite touching ways how important it was to them that the show traveled outside of Chicago, because they felt that it was only there that people give the AACM its due as an organization,” recalls Anthony Elms, the ICA’s chief curator, who adapted the exhibition, which originated at Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art. It’s subtitled Experiments in Art and Music, 1965 to Now. “Outside of Chicago, people talk about Jeff Donaldson being a great painter, or Muhal Richard Abrams being a great composer, or George Lewis being an amazing thinker and composer. But they don’t tie these people back to the group whose tenets they believe in and still operate under.”

The AACM was founded in 1965 by Abrams and three other young South Side musicians: Jodie Christian, Phil Cohran, and Steve McCall, who wanted to create a support network and break out of the model of jazz musicians confined to performing popular standards. Soon others, including George Lewis, Douglas Ewart, Anthony Braxton, Roscoe Mitchell, and Henry Threadgill, joined them. (Another outfit whose membership often overlapped with the AACM’s was the Art Ensemble, which officially became the Art Ensemble of Chicago when it traveled to Paris in 1969.) Soon a visual counterpart, the African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists (AfriCOBRA), emerged on the scene, driven by a belief that art could foster social change. For all the experimentation, their prints and paintings aimed for a mass audience, and sometimes featured bright, mosaic-like patterns and heroic figures. An early example of the latter was the 1967 Wall of Respect, a 20-by-60-foot mural on the outside of a South Side tavern, which helped spark the community-mural movement. Last month students from Olney Charter High School, aided by ICA and Mural Arts Philadelphia, began painting a contemporary version of the Wall of Respect.

Afterword via Fantasia by Catherine Sullivan, 2015.

Many of the artists and musicians believed that the boundaries between music and visual arts were permeable, and some worked in both. As a result,The Freedom Principle is a large-scale, multi-media exhibition bursting with avant-garde jazz and raucous color. Along with its companion exhibit— Endless Shout, a series of installations and performances—The Freedom Principle takes up the entire ICA.

“The show is much more colorful than many art shows you’ll see here,” says Elms. “Not to stereotype us, but you’ll normally see a lot of black, a lot of gray, a lot of white, a lot of subdued tones. This show’s got garish coloring, garish forms, going every which direction. It’s definitely a more celebratory, exuberant approach.”

Telling the backstories of the art and the organizations was important but challenging at times, he acknowledges.

“Normally we don’t have exhibitions that are so historical, so to have a show where you actually have to think about, ‘Does someone know this fact from ’65?’—those were considerations for us, because we normally only have to explain the artist and the artist’s idea. We wanted to think through ways of how to make it open and inviting for people.”

Music sets the tone as soon as you step into the stark space on the first floor that serves as a kind of antechamber. A large, two-sided flat screen is showing Stan Douglas’s Hors-Champs video, in which a quartet led by George Lewis and Douglas Ewart plays Albert Ayler’s “Spirits Rejoice.” The music veers from the wonderfully playful—with nods to the “Marseillaise” and the bugle fanfare at horseraces—to moments (mostly in the percussive solos) whose appeal may be limited to aficionados of the genre.

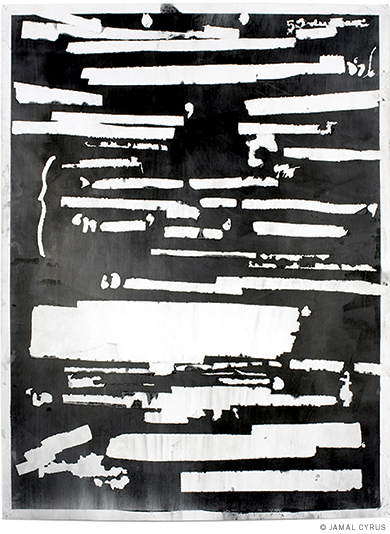

Cultr-Ops by Jamal Cyrus, 2008.

“I’m a music nerd, and I learned early on about the AACM and became interested in the music and tried to track down the records,” says Elms. “What I like about that group, and then seeing a show that uses that as a structure to build out into contemporary art, is that they were open and willing to experiment. They were willing to be a little off the wall or corny at times; they weren’t afraid of finding the limits of any form. And they were also extremely multi-generational—the stuff by elders is just as crazy and just as exploratory as the stuff by [younger] artists. That’s allowed us to have a conversation across generations, across geographies, across mediums.”

A few more highlights from the exhibition:

- Rio Negro II, also by Lewis and Ewart, an almost hallucinatory garden of colorful, mechanically driven rain sticks, chimes, and other percussion instruments.

- Native Son (Circus), by the late Penn fine-arts professor Terry Adkins, a circular assemblage of 36 cymbals (electrically wired to magnets) that bursts into percussive sizzle at seemingly random intervals.

- Sanford Biggers’ Ghetto Bird Tunic, which is somewhere between an outlandish full-body costume and a sculpture of feathers. Adkins wore it for a 2009 performance.

- Charles Gaines’ Manifestos 2, which takes such spoken and written manifestos as Malcom X’s 1965 speech at Detroit’s Ford Auditorium and Olympe De Gouges’ 1791 Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen, scores them on paper through a process that connects musical notes with letters, and offers the resulting music (arranged for multiple instruments by composer Sean Griffin) on video.

- Jam Pact/JelliTite (for Jamilla), Jeff Donaldson’s dazzling, mosaic-like painting, whose intricate geometric patterns gradually reveal faces and hands playing a long-neck bass or a mouth singing into a microphone.

- The musical-score-based collages of saxophonist/composer Matana Roberts.

“What you see downstairs is, by and large, a total blending of media,” says Elms. “It was really an ethos of art, music, how you dress—all this is part of life and a way of being in the world and of asserting an identity and presence in the world. There’s definitely a sort of black-liberation, black-power aspect to it, but as militant as that is in some quarters, in others it’s just looking at a different way of constructing the world.” —SH