Two exhibitions and a new book of images by a physician-turned-photographer.

By Andrea K. Hammer

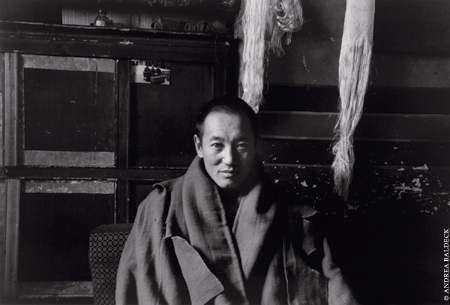

Andrea Baldeck M’79 GM’84 strips away color. Through contrast, contour, light, and shadow, she reveals the essence of her subjects in countless shades of black and white. Her images in Himalaya: Land of the Snow Lion—a new book from the Penn Museum and an exhibition there that runs through early March—illuminate the texture of craggy rocks and the sweeps of expansive landscapes as well as everyday details: from hanging kettles to the patterns that emerge from window latticework. And by capturing the spirit behind wizened faces and soulful eyes, she creates a profound sense of connection across continents.

“So much of photographing, when traveling, depends on the culture in which you find yourself,” says Baldeck, whose other books include Touching the Mekong; Venice: A Personal View; Closely Observed; and Presence Passing. “If you’re in a developing country, you have to get a handle on how people feel about having their images taken.

“It’s difficult for a non-Muslim Westerner in Muslim countries,” she adds. “But it was also difficult in Haiti. Because when you’re in a place where people have so little, giving their image is a significant act, and they want something in return.” In that case, she was able to facilitate cooperation by donating the proceeds of one of her earlier books, The Heart of Haiti, to the Hôpital Albert Schweitzer.

It was in Haiti and Grenada that Baldeck served several stints as a volunteer physician after graduating from the School of Medicine in 1979. (Before medical school, she had been a classical musician who played the French horn and flute.) After 12 years practicing as an internist and an anesthesiologist, she decided to pursue her childhood passion of photography full-time.

By then Baldeck spoke enough Creole to talk with Haitians, and she knew the importance of establishing trust and putting people at ease before pulling out her camera.

“I also traveled in the countryside with hospital employees who were Haitian, so that I didn’t come along as this bizarre, single white person,” she says, noting the importance of trekking, camping, and hanging out on the streets. “In my travels in Southeast Asia and the Himalaya, I was with a small group of eight to 10 people and a local guide who was fluent.”

Some people still refused to be photographed, Baldeck notes, a reticence she has always respected. But many others were equally curious about foreigners.

“Sometimes you have to wait with the camera and be aware of it, which already marks you out,” she says. “You just traipse around for a while, and once you’ve done enough preliminary looking, you can start to ask.”

During this exploratory period, Baldeck takes time to scope out settings and details that capture the mood of a place, and to find locations that “put someone into the picture” who would never travel to these locations.

“Then, I’m looking for the faces,” she says. “Because what do we connect with best in a photo? When we see someone who looks like us and reminds us that we’re human. Those are the faces that inhabit this location and who have accumulated these details.”

The images continue to resonate in Baldeck’s memory after she returns from a shoot. “The limits of film and paper are such that they’ll never match the retina and the brain doing the real work for us visualizing the world,” she explains, adding that her medical experience has honed her perceptions. “If you have someone who is chronically ill or malnourished or in pain, that shows so vividly in their face and body. That’s something that you learn to see in medicine. In photography, you’re also aware what’s coming through in the expression of your subject.”

Baldeck’s fascination with botanical still-lifes—first sparked by her father, a horticulturist—has yielded another exhibition, The Texture of Trees, which opened at the Morris Arboretum November 1 and runs through next September.

“I’m not so interested in taking a photo of a beautiful flower as I am in trying to figure out how it’s put together: its incredible structures and the remarkable sophistication and variation in nature,” she says. “We’re so human-centric that we don’t think about that very often.”

The mind behind those photographs maintains an acute awareness of the non-visual aspects of a place as well. In the tropics, that might be “the heat and humidity, the sound of the insects in the forest,” she says. “You enter a temple, and it’s the incense, the oil from the lamps that are burning, and very often the susurrations of prayers that are going on in corners—and bells and cymbals and the quiet feet.

“I think it’s hugely helpful to be reminded that there’s another world out there,” Baldeck adds. “We think that we have a superior culture, but there are many other ways of looking, believing, and relating to each other and the environment.”

Andrea K. Hammer is the founder and director of Artsphoria: Celebrating Arts Euphoria (www.artsphoria.com).