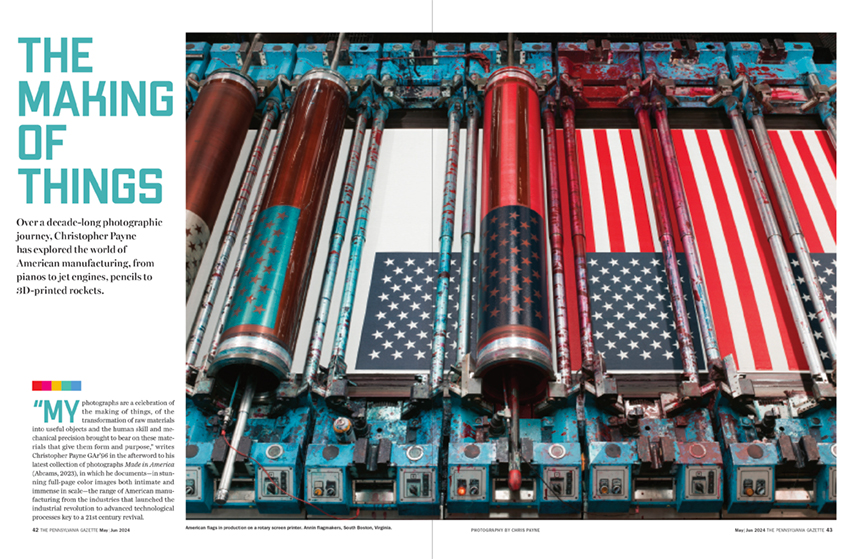

Over a decade-long photographic journey, Christopher Payne GAr’96 has explored the world of American manufacturing, from pianos to jet engines, pencils to 3D-printed rockets.

Photography by Christopher Payne

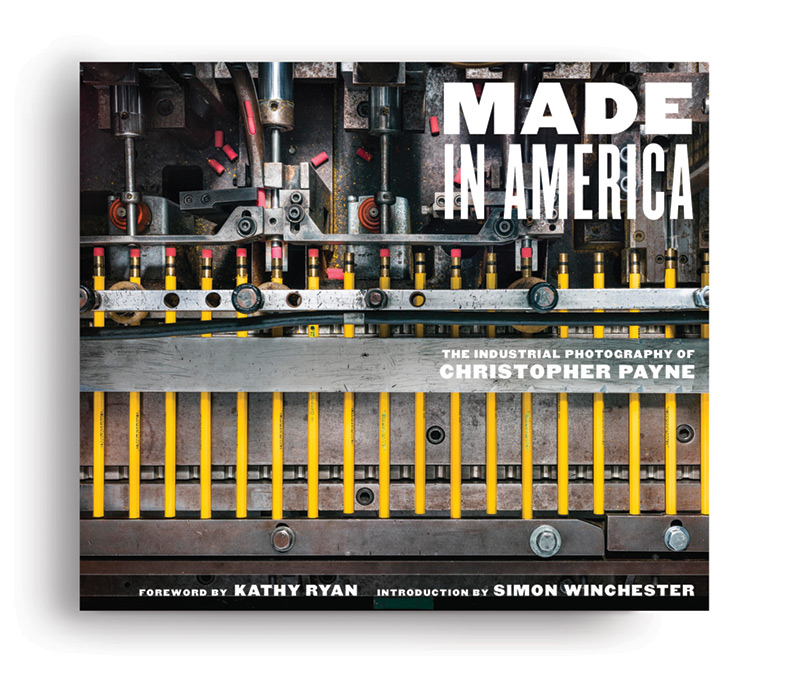

Photographs by Christopher Payne, Foreword by Kathy Ryan, Introduction by Simon Winchester

Abrams Books. 240 pages, $85

“My photographs are a celebration of the making of things, of the transformation of raw materials into useful objects and the human skill and mechanical precision brought to bear on these materials that give them form and purpose,” writes Christopher Payne GAr’96 in the afterword to his latest collection of photographs Made in America (Abrams, 2023), in which he documents—in stunning full-page color images both intimate and immense in scale—the range of American manufacturing from the industries that launched the industrial revolution to advanced technological processes key to a 21st century revival.

Through a mix of personal projects and assignments, including for the New York Times Magazine, Payne has spent a decade on a “photographic journey to learn more about what’s made here.” In some cases, he was free to come and go as he pleased and wait to find the right moment and ideal shot. In others, he had only a day or two to photograph in a factory that might cover a million square feet or more, which he compares to “looking for a particular leaf on a giant oak tree.” (In general, he notes, factory access has become harder because of concerns over safety and intellectual property and the passing of the days when companies “spent lavishly on annual reports and were eager to pull back the curtain for popular magazines like LIFE and Fortune.”)

Depending on the industry, some factories have stuck with the same methods over time, others have reinvented themselves as “new applications for their products have come into existence,” and some newer facilities “have redefined the very concept of ‘factory,’” Payne writes. But all of them “share a commitment to craftsmanship and quality that can’t be outsourced. There is, for sure, a certain romance in the idea of making our own goods here in the US, but it is no longer entirely nostalgia; it is also opportunity and necessity.”

Describing his approach, Payne points to the weight he places on history and to conveying both “useful information—and beauty!” in his photographs. “To do so, I try to understand my subject—how does it work, what is the most essential part of the process, how is it unique?” He attributes that “immersive technique”—as well as the origin of his interest in photography—to his experience as an architecture student working summers with the Historic American Engineering Record, a National Park Service program “entrusted with documenting the nation’s industrial heritage.”

Payne’s job was to execute drawings of “old bridges, grain elevators, and power plants,” but he was impressed by the HAER photographers who “transformed these humble structures into architectural masterpieces.” He originally planned his first book, New York’s Forgotten Substations: The Power Behind the Subway, to be a collection of similar drawings, but the snapshots he took as a memory aid “soon became my passion,” and he learned photography over “hundreds of hours locked inside these buildings, imagining the decrepit, abandoned interiors as stage sets, and making plenty of mistakes along the way.”

For Asylum: Inside the Closed World of State Mental Hospitals [“Architecture of Madness,” Mar|Apr 2010], Payne visited some 70 facilities in 30 states, most completely abandoned or operating at a fraction of capacity, to evoke the history of institutions that once formed self-contained communities where, as the neurologist and writer Oliver Sacks put it in the book’s introduction, inmates could be both “mad and safe.”

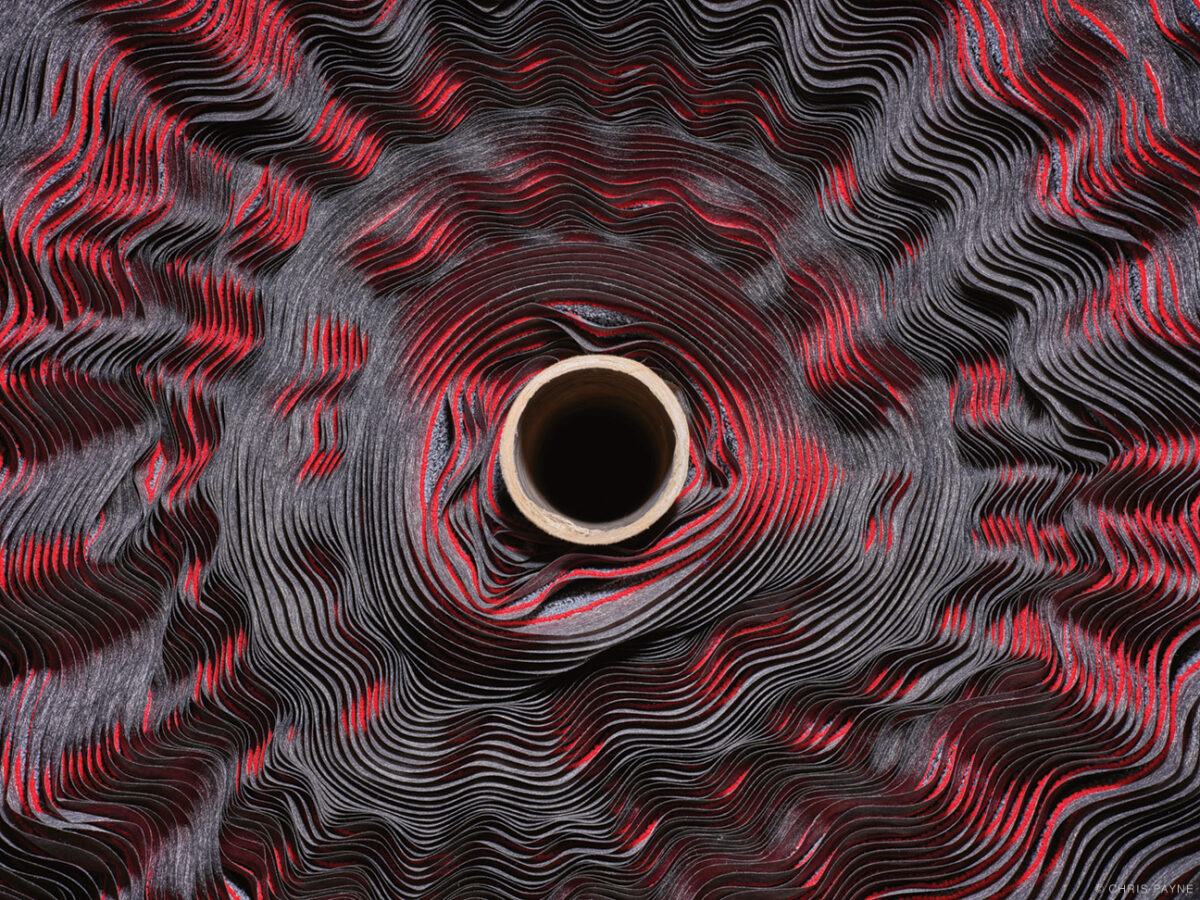

Payne cites as the starting point for the new book a visit he paid in 2010 to a yarn mill in Maine that reminded him of hospital workshops he’d photographed for Asylum. He went on to discover other mills and to become friendly with the owners, who “in addition to opening their doors, would inform me on more than one occasion of a colorful production run, an invaluable tip that transformed a drab, monochromatic scene into something photogenic and magical.” They also shared the challenges of keeping their businesses going in a globalizing economy—as when one shirt factory owner promised him an image that would capture “the narrative arc of the textile industry in America,” only to reveal “a vast, empty hall” with the explanation “‘Gone to China.’”

Payne notes that he had expected to be shown “a room with endless rows of spinning frames, like something out of a Lewis Hine photograph,” and the social reformer who documented child labor at the turn of the 20th century is one of the influences he credits in the afterword, along with the World War II-era photos of Alfred T. Palmer. His work for the Farm Security Administration (FSA) and the US Office of War Information featured “factories, shipyards, dams, and power plants all over the country,” and he is best known for his portraits of men and women working in aircraft factories, which employed dramatic lighting to highlight his subjects and reduce visual clutter “just as common in factories then as it is now!”

Textiles are one focus of the book’s first section, “Traditional Craft,” and other highlights include the Steinway & Sons piano factory in Queens, New York; Martin Guitars in Nazareth, Pennsylvania; a pencil factory; and makers of boats, hats, and roller skates. Payne felt a personal connection to the Steinway factory, which he first visited in 2002, because his father and grandmother had both been pianists. After their deaths, “my memories of the factory took on a more profound, spiritual importance, and I felt an obligation to return to take pictures of the instruments so deeply connected to my family.” The resulting series pays tribute to the extraordinary craftsmanship of Steinway’s manufacturing process by “deconstruct[ing]” the familiar shape of the piano “into its unseen constituent parts” to offer “a glimpse into the hidden choreography of production.”

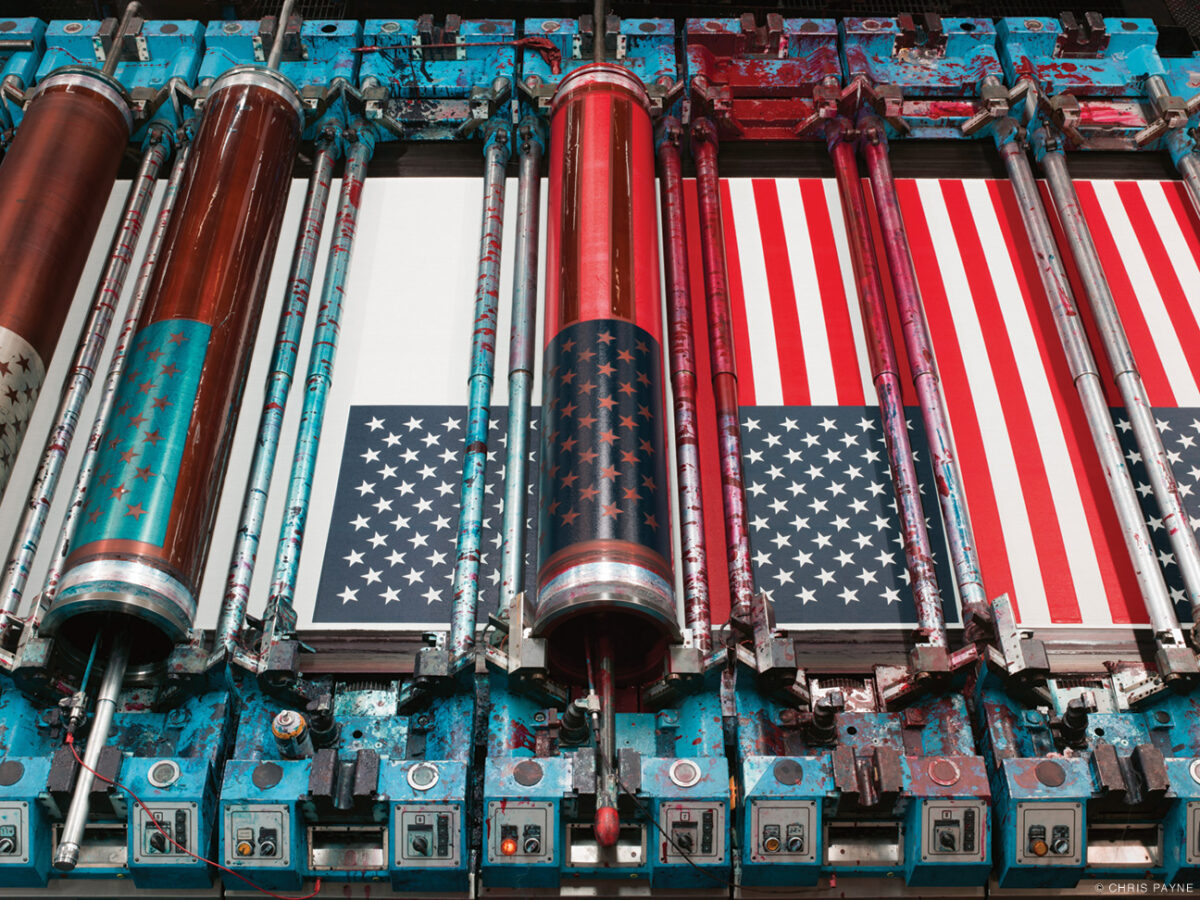

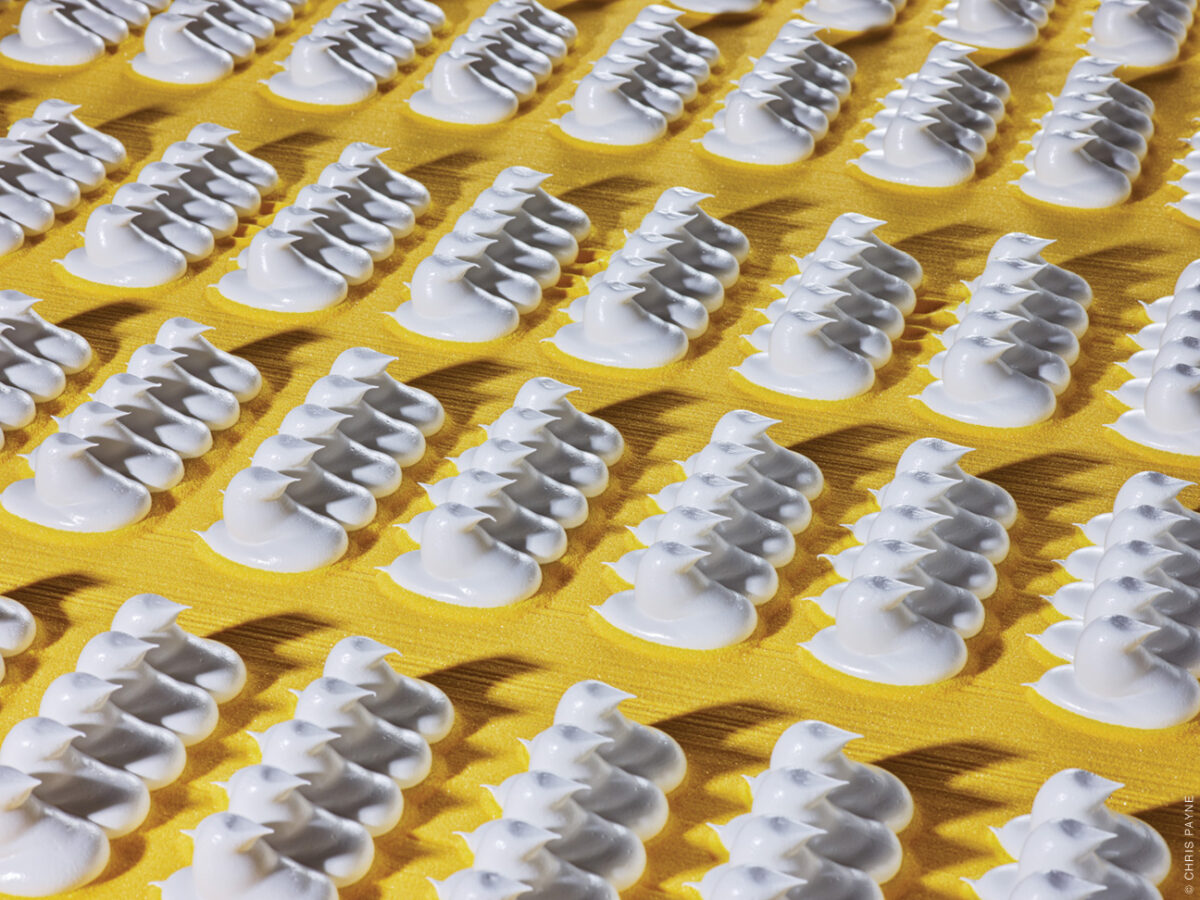

The middle section, “Production at Scale,” has Payne documenting the steps involved in hatching the iconic marshmallow treat PEEPS, printing the New York Times, assembling a variety of household appliances, and building huge and complex mechanical devices like jet engines, container ships, steam turbines, and nuclear submarines.

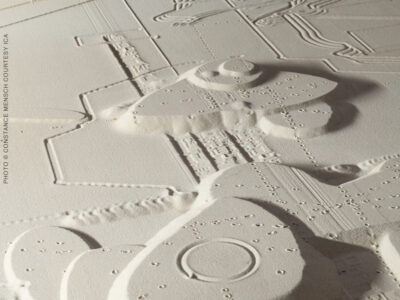

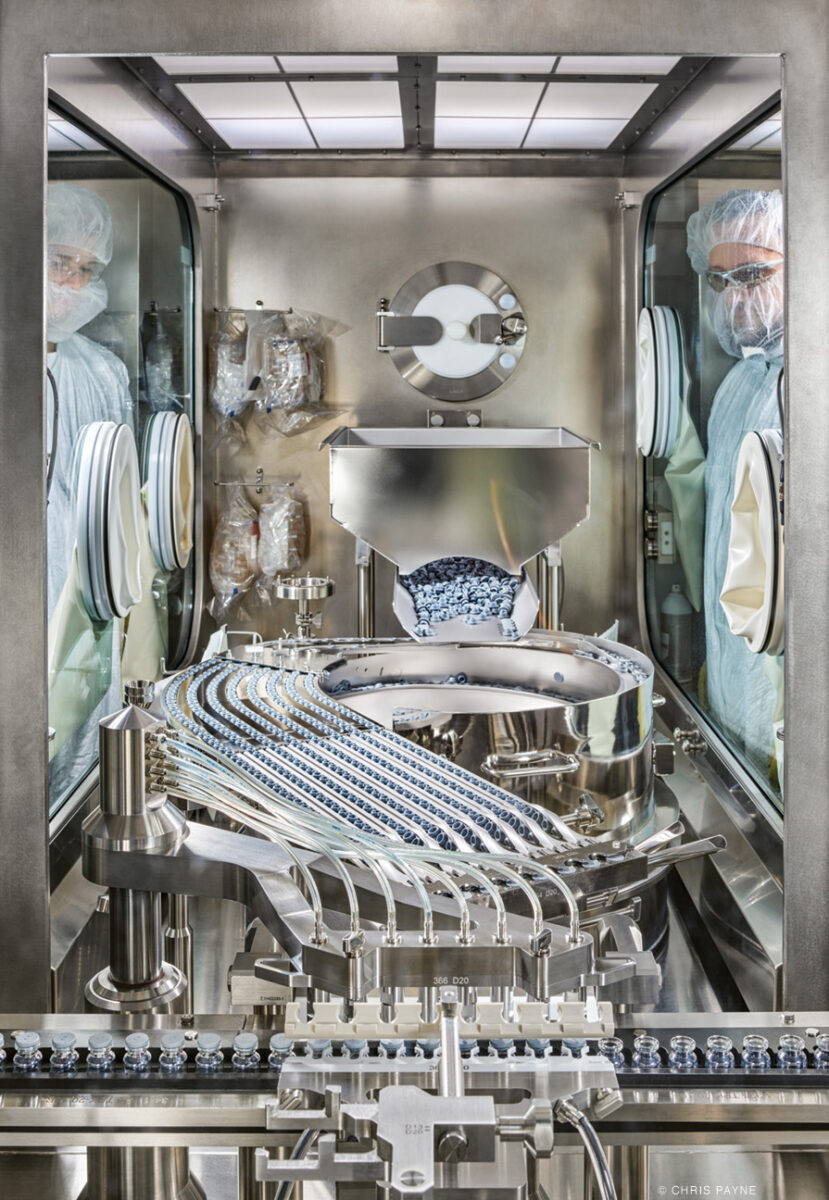

While there’s still an element of gigantism in the book’s final section, “Making the Future,” the emphasis is on precision work with high-tech materials in controlled, laboratory-like environments. Payne shows work involving fiber optic cables, ribbon ceramics, silicon wafers, and the making and filling of glass vials for COVID-19 vaccines, as well as electric vehicle assembly lines for Tesla and Ford; fiberglass wind power blades; and Stargate, the world’s largest 3D printer, in the process of printing a rocket. Rolls of carpet seem to hearken back to an earlier era but have “carbon-negative” backing.

Whether old school or high tech, Payne emphasizes the commonalities across the industries he has photographed. “Along the way I’ve come to believe in the resilience of our manufacturing sectors and am reminded of the genius and ingenuity of American mechanical engineers, inventors, and makers of the machines,” he writes. “Through their work, one can find common ground between the old and new and see a future where traditional and cutting-edge methods both play a role in our economic well-being.” —JP