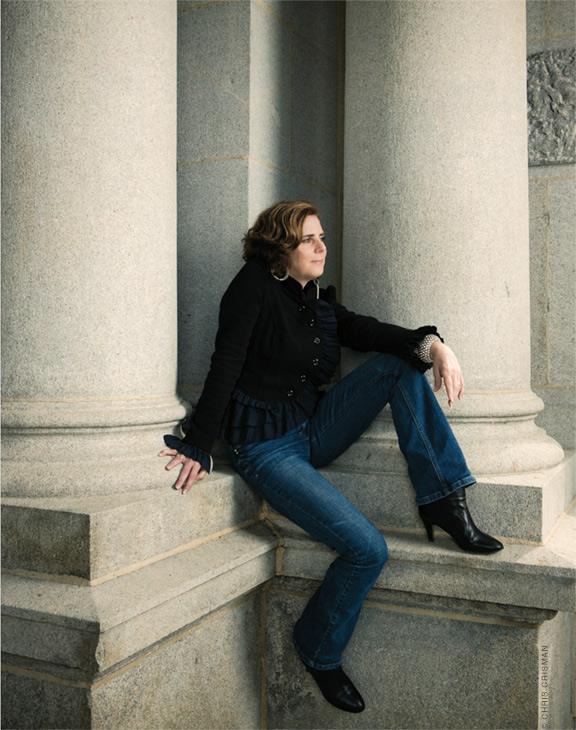

“I think that what is changing about my writing is my willingness to go darker so that I can come out with more light,” says memoirist and fiction writer Beth Kephart C’82. In her new novel, set in Philadelphia during the Centennial, a young woman contemplates suicide following the accidental death of her twin.

By John Prendergast

Photography by Chris Crisman C’03

Plus: An excerpt from Dangerous Neighbors.

Beth Kephart C’82 doesn’t sleep much. “Last night I went to bed at eleven, and I woke up at one in the morning,” she says. “So there’s a lot of day in there.”

While most of us, faced with such a situation, would probably roll over and go back to sleep, “I take advantage of the time I have,” Kephart says. That may help explain how she has managed to publish a dozen books in as many years. (Not that she can count on devoting those wee hours entirely to her literary writing—she also runs a “boutique” marketing-communications firm, some of whose clients are in Singapore, India, and other faraway time zones, “so they have me up” as well, she adds.)

Kephart’s work has attracted praise from critics and fellow writers for its close observation and lyric intensity, and she has built an audience that, if not the stuff that bestsellers are made of, is both enthusiastic and devoted. (“Yay!!!” “Hurrah!” and “I can’t wait to read it!!” were typical comments greeting Kephart’s recent announcement of a new book deal on her blog, beth-kephart.blogspot.com.)

Raised in suburban Philadelphia, Kephart majored in the history and sociology of science at Penn [“Coming Home,” Nov|Dec 2000], but she has been writing “since I was nine,” she says. Poetry was her first love, and is a continuing one—one of the joys of blogging, she jokes, is that she gets to publish her own poetry—and she also placed short stories in literary magazines early on. But she made her first real mark as a memoirist, with the publication of A Slant of Sun: One Child’s Courage, which was a finalist for the National Book Award in 1998. It was followed by four more memoirs exploring issues of friendship (Into the Tangle of Friendship: A Memoir of the Things that Matter), the mysteries of romantic love and marriage (Still Love in Strange Places), parenting that gives kids space to dream (Seeing Past Z: Nurturing the Imagination in a Fast Forward World), and coming to terms with middle age (Ghosts in the Garden).

Among her other works is Flow: The Life and Times of Philadelphia’s Schuylkill River [“Channeling the Schuylkill,” July| August 2007]. A pairing of vignettes told in the voice of the river itself and explanatory footnotes ranging from the Schuylkill’s beginnings (“like all rivers … the product of crustal deformations and time”) up to the near-present, Flow is Kephart’s most unconventional book and appears to be a current touchstone for her.

Kephart also writes essays and book reviews for magazines—including, occasionally, the Gazette—and teaches writing at Penn and elsewhere. Since 2007, she has shifted from memoir primarily to fiction writing, publishing a series of young adult (YA) novels. The first was Undercover, which centers on Elisa, a 15-year-old ice skater with a sideline in ghostwriting love letters for the boys in her high school (the class is studying Cyrano de Bergerac).

The mood is considerably darker in Dangerous Neighbors, her fifth novel, published in August, which stretches the boundaries of the YA category in telling the story of two sisters in Philadelphia at the time of the nation’s Centennial celebration in 1876. As the book opens, 19-year-old Katherine is meticulously planning how she will commit suicide, overcome with guilt and grief over the death of her twin sister Anna. In a scene indicative of the book’s deep engagement with Philadelphia history, she passes through the streets of Center City to the Philadelphia Colosseum, which then stood at Broad and Locust streets, where she views a cyclorama of “Paris by Night” and then makes her way to the roof, planning to throw herself off, imagining “the unbending nature of the street. The smack of absolution.”

But her plan is thwarted by Bennett, Anna’s lover, who has spotted her and followed, and she is forced to return home “with too much time to remember.” The book shifts into the past as Katherine, who has always felt responsible for Anna, the “more delicate twin … who often stood too dangerously close to things,” recalls the events leading to her death in an accident when the girls slip away to go skating on the frozen Schuylkill River, where Anna plans to meet Bennett. She drowns when the ice cracks while Katherine is off skating elsewhere.

Kephart deftly sketches in the sisters’ intense bond—disturbed when Anna secretly falls in love with Bennett, a “baker’s boy”—and home life (loyal cook, a mother distracted by feminist politicking, a reticent businessman father), and she does a superb job of evoking the sights and sounds of the era, both in the city streets and on the Centennial grounds in Fairmount Park, and during a summer excursion to Cape May, New Jersey, where Katherine digs for clams with her father in a rare moment of informality. Drawing on real events, Kephart stages the book’s climax during a fire that burns down the shantytown set up opposite the Centennial’s Main Exhibition buildings (see excerpt on page 66).

Dangerous Neighbors “came out of a lot of places,” says Kephart. “It came out of my love for writing Flow and my love for the Schuylkill River, and from some surprise discoveries I made during the research for that book, and the fact that I love this city,” she says. “My books are very different from each other, but they are about place. They do take place on the Main Line, or they take place here in the city of Philadelphia. Place is character for me.”

The novel went through “many, many drafts,” she says. “It was in fact told in the voice of the fire for the first draft—for the first several versions of that draft. And the next draft is all told in the voice of William,” a somewhat mysterious character whose path intersects with Katherine’s several times during the book and who helps supply the novel’s guardedly hopeful ending. “I could tell you everything about William, but you know very little” about him in the book as published, Kephart says.

“For every sentence you see there, not only has that sentence gone through multiple changes, but I take out 70 percent. Even when I think I’m done, after all of the layers, I take out about 70 percent,” she adds. “Just as I did with memoir, I work toward certain themes. And I don’t want anything to get in the way of those themes.”

(Kephart’s fascination with the city’s history clashed with her book’s rigorous structural requirements—there was a lot she wasn’t able to squeeze in. She resolved the conflict by creating her own teacher’s guide for the book, which provides information on how the Centennial was organized and funded, the exhibition buildings—of which only Memorial Hall, now the Please Touch Museum, remains—and highlighting figures who receive only fleeting mention in the book, like Elizabeth Duane Gillespie, “Benjamin Franklin’s great-granddaughter, a tremendous feminist who made the Women’s Pavilion on the Centennial grounds possible,” and George Childs, philanthropist and editor of the Philadelphia Public Ledgernewspaper, whom Kephart calls “my hero” and “my favorite Philadelphian.”)

Kephart was first attracted to the memoir form when she stumbled on Natalie Kusz’s Road Song, about her experiences after her family moved from Los Angeles to Alaska when she was six years old, in a Princeton bookshop years ago. “I was stunned by that form, by the quietude that Kusz brought to her personal story.”

Though she remains “very comfortable with that ‘I’ voice,” after having written several memoirs she felt that she had come to a kind of end. “Really I thought, when I wrote Ghosts in the Garden, which was my fifth book, that it would be my last. And then the river beckoned.”

Kephart calls Flow “perhaps the most true of my books. I understand that river very well. I understand her heartbreak, her losses,” she says. “And then I discovered, ‘Wow, I can move toward fiction.’”

Laura Geringer—then an editor with HarperCollins’ HarperTeen division and now with Egmont USA, which published Dangerous Neighbors—had written Kephart a long letter in which, “she basically said, “I’d love to see you writing young adult fiction,’” Kephart recalls.

In 2001, Kephart had chaired the National Book Awards Young People’s Literature jury, “which forced me to read about 165 books,” she says. She also had a long history of teaching writing to children, which is a theme in the memoir, Seeing Past Z, “so I kind of knew what [young people] were interested in and what they were reading and what they were aspiring toward.” Nevertheless, she was unfamiliar with the most popular young-adult novel series—and still hasn’t read them, she says—and was reluctant to write in the genre “because I didn’t know how it was done.”

It took about a year of back and forth, but she changed her mind after Geringer paid a visit to Philadelphia to meet with her. “She asked me what I had been like as a teenager in high school during our conversation down here,” Kephart recalls. “And I told her, you know, ‘I was an ice skater. I was rather invisible. I wrote poems. Boring.’ And I kept deflecting, as I always do. And she said, when we were walking back to the train station, ‘[That] sounds interesting to me.’”

“And I got on the train, had some scrap paper, wrote the first 10 pages of Undercover. And that’s how that book started,” she says. “And it became very meaningful to me. I [have] really enjoyed writing those books. And all of those characters have so many pieces of me in them.”

Another satisfaction was the interactions she began having with her audience. “I got involved in this whole blogosphere, and I started to hear from these young readers,” Kephart says. “And the sort of ecstatic high of interacting with young people in that way was tremendous. And sometimes I get to meet them now.”

While the designation YA is “meaningful to the publishing house and to the bookstores that have to shelve those books,” she says, it has limited value for readers. “I would suggest that 65, 75 percent of my readership is adult.”

Of her novels so far, she considers Undercover and The Heart is Not a Size, which deals with anorexia in a story of two friends who go on a school-service trip to Mexico, as being closest to a conventional young adult novel “because of the conflict at that youth level.” But a book like Nothing but Ghosts, about a young woman whose mother has died “was very meaningful to a lot of women my age who have just lost their mother,” Kephart says. “A lot of my books have these adult interactions.” In the case of Dangerous Neighbors, Katherine and Anna are 19 years old, she notes. “The writing is clearly for anybody who wants to read a book decorated with lyrical prose. So I never ever write to genre or category. Good or bad, I don’t know.”

Kephart relishes the research process for her books (“Writing is the best excuse for reading,” she says), amassing a library of material related—though sometimes distantly—to the work at hand. She has “a tower” of books on the “history of Philadelphia and everything else” gathered for Dangerous Neighbors, and she mentions old recipe books and descriptions of hydrotherapy as among her recent sources. “When you research you find out about how other people live, or what other people know, or what excites other people,” she says. “And so it de-isolates the process. I’m not that interesting, and I don’t know very much. So I’ve got to go to other people’s books.”

She typically has more than one book under way at a time. Her writing process has developed over the years—she recently began writing early drafts by hand, for instance—but “What remains is a great reliance on seeing, and the photography that I do; a lot of movement, dance, and walk that gets me into the lyric and sound of the sentences that I make,” Kephart says. “And I trust myself more to do things that might not be seen as popular.”

Dangerous Neighbors, she says, is a prime example. “Everybody looked at it, and said, ‘an historical, literary novel for young adults, are you kidding me?’” Yet the book scored a starred review in Publishers Weekly, which called it “a tantalizing portrait of love, remorse, and redemption,” as well as receiving raves from many bloggers on books for teenagers and reading in general.

“When you finish a book like Dangerous Neighbors, and when you’re lucky enough to get the reception it’s gotten, you are more fortified in your determination that whatever you do next will feel as original, you know, and rich,” says Kephart.

“I think that what is changing about my writing is my willingness to go darker so that I can come out with more light,” she adds. “Hope comes from a raw place. And at my age now I know that.”

She traces the insight to her work on Flow. “I think that I worried too much early on about beauty. And that is a function of worrying about making beautiful sentences. And in Flow, that river gets awfully angry in the middle of that book. And that allowed me to—I was angry when I was writing about what happened to her environmentally.”

Since writing Dangerous Neighbors, Kephart has finished two more books, one set in the aftermath of the Spanish Civil War and the other inspired by the old Byberry Mental Hospital in Northeast Philadelphia. It doesn’t feel to her like she works unusually fast, Kephart insists, but she does feel a sense of urgency.

The Spanish Civil War book “took 10 years and went through 90 drafts,” while the Byberry one took “three years, several drafts,” Kephart says. “And I’m not talking about editing. I’m talking about utterly different voices, different time periods, different themes.

“And because I work on these books in overlapping fashion and because I have to fight for them to be published, each one is a victory. Each one is a surprise,” she adds. “And I’m a literary writer, of course, not a commercial writer. So it’s harder and harder to be that kind of person in this environment. And every time out I feel this could be my last one. Make it your best one.”

EXCERPT

Dangerous Neighbors

The first flames poke through the raw-boned roof of C.D. Murphy’s Tavern like the ears of a tabby cat, a striping of ochre and black that keeps to itself at first, prowling and small. “But do you see that?” the stranger repeats, and by the time Katherine understands that it is not some Centennial spectacle being ogled but a fire across Elm, others have got the story, too. The sun is playing its duplici-tous tricks, and all about the Centennial grounds shoals of people—one hundred thousand in all—move saturated, stupefied. “But do you see that?” Katherine turns, and just then the fire leaps high and begins to waggle west. In a day of wonders it seems but another one, a shameless curiosity, but right as Katherine has this thought, the fire doubles up on itself and cleaves. Lottie sees it. Lottie punches out her fist and grabs at the nearest hunk of sky.

Down below, in the jumble of Elm, gawkers have arrived, sudden evictees, porters, a tall man in plaid pants, a collection of waiters, a crowd of children running ahead of their mothers. Some of the horses in their harnesses are rearing back, bucking to rid themselves of the weight of the carriages for which they’ve been responsible all day. “The engines are coming,” someone says, but Katherine’s eyes are on the insolent, fast-raging fire, which does not burn in place but keeps on multiplying, pushing its tongue through more burst windows of Shantytown now, as its victims pour onto Elm. One of the hansom cab horses has taken off on his own, his driver galloping behind.

The fire burns in place, seems to consider. It maintains its hold on the east, drops a final curtain on two saloons, blackens Theodore Bomeisler’s hotel, puts an end to Ullman’s eatery. It turns the sky to smoke and now arrives at the door of the Ross House, which is sturdy brick, not wood, four stories high, and where the boarders are work-ing their own rescue like bees in a hive, tossing through windows their trunks, their bedsheets, their instruments of beauty, their twelve-cent Ledgers, as if they cannot bear to leave the news behind. Leave the news be, Katherine thinks, the news is dead.

Now come paired men and a woman with a trundle bed between them; a ransomed velvet chair; a settee with carved swan’s feet and dimpled, upholstered hearts; a gilt frame; a pail of brushes and an artist’s palette. Men and women who seem to have stripped the Oriental run-ners from the stairs within, who seem determined to go nowhere without a corset box, an umbrella stand, a pair of candlesticks. The Ross House cooks stagger about in the streets with their arms clasping blackened cooking pots, soup tureens, porcelain platters, dessert bowls. The salvaged and the salvagers have no discernible plan, and now the fire brigade has come in, and river water from all directions—hard white spitting streams.

The wind is at the fire’s back. It leaps and dazzles and still more boxes are being thrown to the street, and suddenly from one narrow doorway emerges a giantess in a tented dress—the famous fat woman of Shantytown, Katherine realizes—who seems surprisingly fleet on elephantine feet. Elm is all at fever pitch. Elm has been infiltrated, and now the Centennial police have arrived, their whistles shrill above the melee, above the boom of the fire leaping higher.

In Katherine’s arms, Lottie has begun to cry, and when Katherine runs to see the throng behind her on the roof, she understands that the world’s largest building has exceeded its rooftop capacity. Thin as ice, Katherine thinks, pulling Lottie even closer, pulling her straight to her heart.

She would cry for Laura [Lottie’s aunt], but Laura won’t hear. Laura is somewhere down below, and right now, right in this instant, again, Katherine is alone with her terrible responsibility.

Now across the bedlam alley, the final roof timber of C.D. Murphy’s falls. The brigade of amateur firefighters has begun its fight—unblenched paladins armed with buckets and basins of slosh. One man is throwing bricks at the conflagration, as if he could break its neck. but there’s too much summer heat in brittle Shantytown. In most every direction there is the crepitating pop of structure giving way, advertisements in a peel on the smudged faces of the shops, the startling demise of cheap curtains, the shattering of lanterns.

“More brigade on its way,” a woman yells, a chamber-maid, three brooms in her hands, a mop, as if these were the lives most worth saving. Katherine strains and suddenly she sees William with his wheat-colored hair and the sand -colored mutt, down on the ground, near the tavern where this fire first began. Together they run, and now Katherine sees William stop outside Allen’s Animal Show, where a counting pig and a notorious cow are kept, birds in cages, a pair of titanic sea cows. Everyone knows this. Everyone’s read it. William seems to have taken it to heart.

He pounds at the door and lets himself in. He disappears, and the fire is raging, the fire is coming, Katherine realizes, for him, and her heart stops at the thought, her lungs go airless.

When the mutt emerges from the flames he is unrecog-nizable soot—dancing on his hind legs. A cat breaks through the flaming door of Allen’s. A collie breaks free of its own rope collar and leaps, teeth bared, onto Elm.

The walls of Allen’s are crumbling. The ceiling is collaps-ing into embers, and right then, through the almost-nothing of the building that was, a bird comes fluttering free, her wings thwack-thwacking within the grim-gray smoke, a broken chain dangling down from one webbed foot. Katherine remembers Operti’s, the girl with the bird, is suddenly brokenhearted at the possibility of them coming to harm. Where is the girl? Where is the bird? She watches the unchained dove float all the way up through the smoke toward the sky.

The fire burns in place and then, with a new ferocity, it launches, again, toward virgin territory, until the entire alley is flame and fury and finally William appears, black-faced and stumbling, alive.

Alive, Katherine thinks. And it’s the most beautiful word that there is.

The fire is white at its most true. It is yellow, orange, smoke, and plasma in the blistered rags above its heart. It will burn harder with the wind, and like a fish caught in a net, Katherine cannot move. She cannot free herself to return Lottie to Laura. She cannot find the stairs or make her way to the street. She cannot join William in whatever mission he has set for himself, for it is clear to Katherine that he has set out for himself the task of saving things, of rescue.

There is so much pressure at Katherine’s back that she cannot so much as turn to glance over her shoulder, to check just in case Laura has, by some miracle, come, but how could Laura come? What was their promise? Five 0’clock, at the balcony, on the stairs—an impossible prom-ise. There’s no more getting up on the roof now than there is getting down; there’s nothing to do but hold Lottie safe, this little girl who has grown warm-damp now, whose hair is lying flat against her face. A bright pink is flourishing on Lottie’s face, and she has begun the sort of hiccoughing cry that Katherine does not know how to cure.

Beneath her feet the roof feels thin.

Down on Elm, the fire’s evictees keep streaming—-through doorways, from alleys, out of the dark into the blazing light, some of them forming a battering ram that seems intent on knocking the Centennial turnstiles down. They want in to the Centennial grounds. To the lakes and the fountains and the miracles of the exhibition, to the seeming safe haven on the north side of Elm. Against the gates they press, against the keepers, who have wakened from the somnolence of the afternoon. No one will be let in, no one let out, until the fire dies, until somebody can kill it. “The second brigade is coming,” someone says, and now the Centennial police are barricading, holding the terrified masses back. The engines must be let through to do their work. Their horses are frightened and rearing.

The roof deck quails. Katherine feels the simple shud-der of the grand construction beneath her feet, she hears the creaking of bolts and screws, and all of a sudden she is deluged by an awful premonition. One tight thing will go loose. One isolated beam will wrangle free. The roof will yield. Into the unhinged jaw of the Main Exhibition they will fall—through folderol, corsets, crockery, engines, fizz, the hard white light of the perfect jewel, through Brazil and Spain and Norway.

Without choosing to fall, they will fall. Lift. Drag. Thrust. Gravity.

Even the future can vanish.

Smithereens, Katherine thinks. No air. And now she remembers Anna, thinks as she has tried so desperately hard never again to think of Anna in the suck-down of the Schuylkill, between the teeth of ice. It happened all at once, Bennett said, at the river that day, before his hand could reach hers. It happened. There was the sound of something giving way, a white shattering, and she was gone. Under and into the lick of the winter current, over the dam and down, trapped in the bend and stiff, floating above the cobbled backs of turtles, the hibernating congregations of fish, the undredged leaves and sticks, the slatternly remains of a she -dog. Three days later a boy found Anna at the mouth of the Delaware, her muff still hung about her neck.

“There, there.” It’s the woman beside Katherine, who smells like bratwurst, whose scored and dimpled neck is as thick as a club. She chucks a finger the size of a thumb under Lottie’s chin, and if Lottie stills for one abrupt instant, the corresponding scream is power. She shakes and tosses off the touch of the stranger’s finger, and Katherine shifts her, she kisses her forehead.

“It’s all a bit much,” Katherine says, and again Lottie screams, she grows inconsolable. She has become an exhaust-ing weight in Katherine’s arms, kicking a hole in the sky.

“I’ll say it’s much,” the woman harrumphs. “They’ve got us like prisoners up here.” The knot at the back of the woman’s head has come undone, and chunks of auburn hair fall gracelessly forward. Her eyes are small and deep in the full yellow moon of her face, and now Katherine looks past her, to the man on her left, who seems transfixed by the spectacle of fire. Ash bits waft through the air like confetti. There’s the taste of char on Katherine’s tongue.

Lottie wants out. She wants down—her little feet work-ing like pistons so that Katherine has to hold her tight, wrap all her strength around her. “Look, Lottie,” she says, for down below the police have finally succeeded in forging a tunnel in with the fire-fighting steamers. This brigade on Elm has turned its back to the fire. They have raised their nozzled hoses to the pert glass face of the Main Exhibition Building, and now they are firing. Someone near Katherine begins to cry. Long, gulping, inconsolable cries.

“It’s just a precaution, miss,” an old man in a checker–board vest says, as if he’s seen plenty of this in his day.

“Bloody ugly fire,” a British gentleman says, and a Brit-ish woman answers, “Wait’ll I tell me missus.”

The smoke billows and slows. The fire sends bright rib-bons up into the sky and seems to begin to lose some interest in itself. Even as the spectators holler, even as the horses stomp, even as the attenuated roof of the Main Exhibition Building twitches, the fire seems to sicken of its own mad greed. It has fallen from the height of its early spires and has divided. It has failed to launch across the processional width of Elm. It has bowed its head in places to the streaming river water. William and his mutt have disappeared. Kather-ine searches for them. She sends her hope out to meet them. Her hope for rescue. For the return to life.

In Katherine’s arms, Lottie is lying perfectly still, asleep now, her face mushed to Katherine’s shoulder, her weight sunk against Katherine’s slim hip. For the first time she wonders how Laura has done this all day and all week, how mothers do it, and she thinks of her own mother, efficient and brisk, trying to calm twins. It is impossible to remember her mother’s touch. Katherine only remembers Anna, the early sweet frustration of confusing her sister with herself.

The sun has fallen. Soon the moon will be on its way. In places, still, the fire is being fought, but even more so now, the fire loses, and there is no more need for the bri-gade on Elm; the horses are being hitched back to their engines. There is no more need to lock the people in or out; there is the sound of turnstiles clicking. There’ll be smoke, Katherine thinks, for days. There’ll be the hovering smell of char and ash, but already now some patches of sky are clearing, like a fog rolling off, and between patches Katherine gains a broader view of Elm and Shantytown below, the spoiled victims of the fire, the porters out in the street, the waiters with their fistfuls of silverware, one cook with a bloody back of beef on a tray. The swappers, vendors, dealers, den masters, chambermaids with pots walk the streets in a daze. The hooligans and harlots. One woman ambulates with a fringed parasol popped high, saunters, almost, among the dazed.

At Katherine’s back, some of the pressure eases, as finally some are making for the stairs, drawing themselves back down into that paradise of progress, the industrious songs of machines and fountains, in search of the ones they left behind. “They’ve got the organ started again,” someone claims, but Katherine only hears the sound of the street below, she only keeps looking out upon the mangle and mess of Shantytown. Her hips, her arms, her spine are aching, but Lottie must not wake, Lottie must be kept in her incubated slumber until she is with her aunt again, and Katherine understands that she must stay here, in this one place. That Laura will come looking. That they will be found.

Now something down below pricks Katherine’s eye. Some distant strangeness that is even more strange than all that has gone before, and in an instant she understands: it’s that mutt. Looking like a wolf or a bear in its mangy sooted coat, prancing like a circus act at the door of the Trans-Continental Hotel. That mutt. That mutt, alone. Her heart hard-walloping against her chest, Katherine strains to see past the dog, beyond it, to William, who must be near—it is desperately important that William be near. For he res-cued that pig from the Chauncers’ garden, and he stood beside Katherine at the bakery door, and he was there—he was there—before Katherine abandoned her sister. He is part of her before, a one right thing in a dangerous world. Past the fire, past the smoke, through the detritus and ruins, she strains to see. Up and down, but she sees nothing. Only the mutt trotting in its circle.

“There, there,” that woman beside her says. “They’re let-ting us down now, do you see? Danger’s over.” She puts a hand on Katherine’s shoulder. Katherine doesn’t turn.

“No,” Katherine says. “No. But thank you.” For she has her eyes on that mutt and she won’t divert herself this time; she cannot afford, ever again, to stop paying attention. If she has learned anything from Anna’s dying, it is vigilance. She will live her whole life forward now, on guard.

The pressure behind her keeps easing. The tarnished sun is gone from the sky. A breeze is bringing evening in, and somewhere high above, the stars have agreed to populate the night, to hang above the hordes below who are desperate for passage over the river, to the city, who are packing streetcars, carriages, cabs, who are giving up and walking home.

Excerpted from Dangerous Neighbors, copyright ©2010 Beth Kephart. Reprinted with permission of Egmont USA.