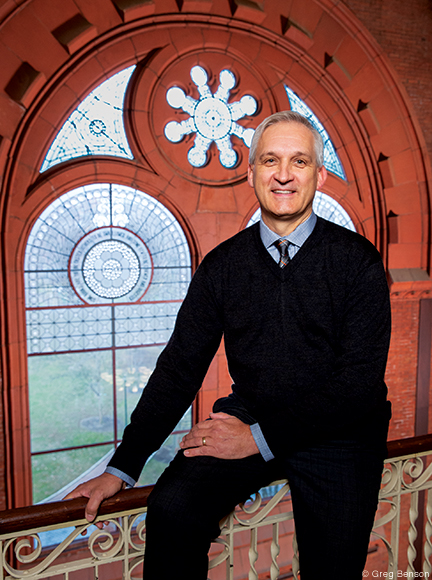

Planning chief—and multiple alumnus—Mark Kocent named University Architect.

The first contribution that Mark Kocent C’82 GCP’91 GFA’91 made to Penn’s architectural heritage came when he was a senior and his design was chosen for the Class of 1982 Ivy Stone. His sphere of influence has expanded since then.

In June Kocent was named University architect in the Division of Facilities and Real Estate (FRES), succeeding David Hollenberg GAr’75, who retired last summer. But he won’t need help finding his way around the office. His new position followed a 14-year stint as Penn’s principal planner, managing the creation of Penn Connects, the University’s 30-year master plan.

In its first two phases (2006–2017), Penn Connects guided some $3.8 billion in capital investments to produce more than 6 million square feet of new construction, another 2.7 million square feet of renovations, and 30 acres of additional open space. The recently launched Penn Connects 3.0 (2017–2022) incorporates many of the key capital projects included in the University’s $4.1 billion Power of Penn campaign [“Gazetteer,” May|June 2018].

“Collectively, we’re the stewards of this wonderful collection of 180 or 200 buildings that date back to the 1870s,” Kocent says, explaining the work of the Office of the University Architect.

“When a school or center comes to us and says, ‘We’d like to do a major renovation, or we’d like to do a new building that’s really going to be the game-changer or the strategic initiative for our school for the next five or 10 years,’” he says, the University architect provides expertise in “helping them define what they want and then hiring the architect.”

And while they don’t do design work internally, they do consult with the architects on the design throughout the process. “That’s the lasting piece that we leave for generations of Penn.” Just as in the 1870s, “when someone left College Hall for us to maintain, we’re leaving those indelible pieces,” he says. “And it’s also in the landscape, not just the architecture.”

A design of the environment (DOE) major as an undergraduate, Kocent also has a bachelor of architecture degree from Drexel University to go with his master’s in city planning and urban design from the University. His non-Penn professional experience includes eight years with Venturi Scott Brown and Associates.

Kocent has a vivid memory of arriving at the University from his home in Pittsburgh. “I was a first-generation kid that made it to Penn and probably wouldn’t have made it here if it wasn’t for my mom,” he says. “She lost her husband when she was pregnant with me. So she raised four kids, all went through college and grad school, and on very modest means. But it really taught us a lot about perseverance.”

They pulled up outside the Girard Bank building at 36th and Walnut (which became Mellon Bank, then Ann Taylor Loft, and, in its most recent and extreme makeover, is now part of the Perelman Center for Political Science and Economics [“Gazetteer,” Sep|Oct 2018]). “I remember my brother unloading his light-green Buick Special. It was a 1970-something great old classic car like a Skylark,” he says. “We just went in, got my checking account, and they said, ‘Okay, well, we’ve got to drive back to Pittsburgh, so you’re on your own.”

“The campus then definitely wasn’t as green,” he recalls. “I think they had just finished Blanche Levy Park, or College Green. [But] even then with Locust, it was already a little bit of an oasis in the city.”

One project Kocent proposed for a DOE class—replacing an eyesore surface parking lot between HUP and the Penn Museum where 33rd and 34th Streets meet—ultimately came to fruition in 2013 with the opening of Kane Park, for which he credits the intervention of former trustee chair Al Shoemaker W’60 Hon’95.

Asked to pick the biggest potential design error Penn has managed to avoid in its history, he expresses relief that the University never followed through on demolishing the Furness (now Fisher Fine Arts) Library in the decades when its ornate design was out of favor. Close runner-up: the Stassen-era “Tower of Learning” proposed, but never erected, at 36th and Locust Streets.

Another fond memory from his undergraduate years is of “Al the fruit man,” an older African American who regularly set up shop out of his station wagon around 37th and Locust Streets and became a “confidante,” Kocent says. “I would stop by every day and pick up an apple or a piece of fruit. He used to say, ‘Mark, whatever you do here, use the wisdom you get out of the University to improve the quality of life.’”

Kocent’s Ivy Stone design (located on the School of Nursing’s Fagin Hall) was inspired by Al’s example and also intended as a response to racial tensions roiling campus, where Dubois House had been subject to bomb threats, he says. “It’s a Penn shield, and out of the top of the shield is a series of ivy leaves growing. And it talked about how, out of one Penn, there are many people.”

Today he connects that vision to the University’s expanding initiatives under President Gutmann to promote diversity and inclusion. “To me it was very much the sort of thing that Amy talks about,” he says. “Although I was a white Catholic kid from Pittsburgh, I think I realized the value of the diversity that Penn could offer, because clearly there were many people here who were wealthier than I was that had had different upbringings.”

In design terms, he points to FRES’s ongoing efforts to support minority- and women-owned firms in hiring contractors and design services, and the role it has played in the provision of gender-neutral restrooms on campus, offering Penn’s schools guidance through consultations and prototype designs.

The renovation of Hill House [“Gazetteer,” Nov|Dec 2017] included gender-neutral restrooms to replace the former male- and female-designated facilities. In that case, “we actually got more fixtures per square foot,” he says, as well as shortening the distance to restrooms for many residents. “So it was a good win in a lot of ways.”

So far, Kocent says, his transition has been relatively smooth. “David was a great colleague” in his role as University architect. “We partnered in almost all the projects.”

Smooth, but not easy. Recalling the flurry of feasibility studies demanded by deans and center directors eager to get their projects in front of donors during the Making History campaign, he adds, “since the Power of Penn, it’s sort of like someone just poured gasoline on the fire. Just when you thought Dr. Gutmann was slowing down, she’s like, ‘Look, the next four years are going to be crazy. Strap in.’”—JP