To some people, “waste disposal” means lugging a couple of Hefty bags to the corner twice a week. For David Stoller C’72, it means packing several tons of garbage into shrink-wrapped bales, shipping the giant bundles to landfills hundreds of miles away, and storing them until they can one day be turned into fuel.

TransLoad America, the company Stoller founded in 2002, ships solid waste by rail. With railyards in Michigan, Rhode Island, and New Jersey, and landfills in Ohio and Utah, TransLoad is neither the smallest nor the largest player in the $45 billion solid-waste-management business. But its recent acquisition of a proprietary waste-baling system promises to make it one of the most innovative.

According to Stoller, TransLoad purchased the system from the German firm Roll Press Pack to solve a specific problem. While TransLoad handles both municipal solid waste and construction and demolition debris, the two cannot be shipped in quite the same way. Construction and demolition debris, for example, can be carried in standard rail cars. Under ordinary circumstances, however, municipal solid waste cannot; it must either be carried by truck or placed in special steel containers for rail shipping—containers that must be cleaned, maintained, and tracked as they make their way back and forth between loading stations and rail-served landfills.

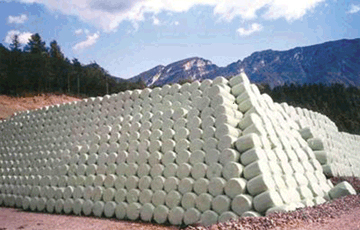

Roll Pack Press developed its waste-baling system to satisfy European regulations governing the pre-treatment of landfill waste, but the technology solves TransLoad’s shipping problem as well. Giant automated balers first shred the waste and roll it into enormous cylindrical bales. The garbage is then compacted to a density of 1,400 to 1,600 pounds per cubic yard and sealed in a thin film of impermeable plastic. The neatly wrapped, multi-ton bundles of trash can then be shipped in ordinary rail cars without the need for those cumbersome steel containers.

The system offers other advantages. For one thing, it eliminates putrescence. Shredding the trash releases much of the liquid that would ordinarily be trapped inside, while compression prevents whatever remains from pooling. Hermetically sealing the bales in plastic keeps odors in and oxygen out, preventing decomposition and the formation of leachate—the yucky and potentially toxic liquid that can seep out of landfills and pollute underlying groundwater.

Because the waste comes pre-compacted, there’s no need to pay someone to bulldoze it at the landfill, thereby saving on labor costs. And while one large semi-trailer of the kind traditionally used to transport loose trash can haul approximately 22 tons of garbage, a single railroad boxcar can carry 100 tons.

Most intriguing, however, is Stoller’s contention that his giant bales of shrink-wrapped trash might someday serve as energy sources.

According to Stoller, converting garbage into energy is the “holy grail” of both the waste and energy businesses.

While the technology to do this commercially doesn’t yet exist, Stoller argues that TransLoad’s baling system will allow waste to be stored indefinitely, with minimal maintenance and environmental impact, until it does. At that point, the bales could be harvested for their fuel potential like enormous, trash-filled fuel cells.

“We hope to be among the leaders in exploiting this opportunity to convert garbage to energy, and the ability to store waste on-site really allows this to be done,” Stoller says. “Ultimately we’ll be depositing it in our own landfills or in facilities that will be converting that garbage into useful products: biofuels, electricity, heat. What you’d effectively create with these bale-fills would be energy reserves.”

Stoller’s interest in environmental issues goes deep, as does his entrepreneurial streak. Undergraduate study in environmental biology led to jobs preparing environmental-impact statements for the Los Angeles Department of Public Health and the Bechtel Corporation. Stoller later attended law school by night while working as director of energy programs at the Scientists’ Institute for Public Information in New York, and eventually became a partner at the law firm Millbank Tweed, where he investigated ways of financing large waste-disposal projects.

In the early 1990s, Stoller joined the Charterhouse Group, a private equity firm. There he became aware of a business opportunity presented by the federal Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) Subtitle D. Subtitle D had the effect of forcing the sale and closure of many small landfills, and Stoller’s first waste-management company, American Disposal, acquired and consolidated such facilities into larger regional ones. Stoller briefly left the garbage business to start a wholesale insurance company, but as the growing distances between regional landfills made rail shipping increasingly attractive, he returned to found TransLoad. Now, with the environmental and financial costs of fossil fuels attracting newfound attention, Stoller once again sees opportunities in the waste business—this time, in long-term storage and energy conversion.

TransLoad is currently demonstrating its baling system on Long Island and in California, and Stoller plans to have a fully operational baling-and-transport operation in place by early 2008. His ambition of establishing a garbage-to-energy conversion empire will take time, but he’s in it for the long haul.

“They say once you’re a garbage man, it’s hard to get away from. There’s something about the business that stays with you,” Stoller says.

“Hopefully, it’s not the odor.”

—Alexander Gelfand