This is the second of three letters written for the Gazette by Dr. Brendan O’Leary, the Lauder Professor of Political Science and director of Penn’s Solomon Asch Center for the Study of Ethnopolitical Conflict. He is working in Hawler (Erbil) as a constitutional advisor to the Kurdistan National Assembly, and served on an international advisory team assisting Kurdistan’s negotiators during the making of the transitional law. His book, The Future of Kurdistan in Iraq (with J. McGarry and K. Salih), will be published by the University of Pennsylvania Press this summer.

The tortuous manufacture of the Transitional Administrative Law of Iraq reminded me of Bismarck’s saying that it is best not to know how either sausages or legislation are made. That said, it is a better transitional constitution than many of us feared, despite the adverse environment from which it emerged.

The Law is an interim constitution, unanimously made by the Iraqi Governing Council and ratified by the Coalition Provisional Authority on March 8. It was produced under the supervision of an ill-informed occupation authority anxiously looking at the U.S. presidential election clock. Shepherded to its conclusion by “The Administrator,” L. Paul Bremer III, it was made without any extensive public deliberation. There was no transparency attached to its construction. The Law was negotiated to its conclusion after horrific and viciously provocative bombs in Erbil, Karbala, and Baghdad, the work of al-Qaeda and its network who are intent on making Iraq an apocalyptic battlefield.

Yet despite these inauspicious birth pangs, the interim constitution has merit. It is republican, liberal, federal, and democratic. It can be the foundation of a voluntary union.

The Law reflects agreement on what was wrong with Saddam’s regime. Iraq will be a republic, without a single president. The foolish idea of restoring the Hashemite monarchy—an idea aired in Foreign Affairs, the journal of the U.S. foreign-policy establishment—received short shrift. The armed forces of the future federation are confined to external security and placed under civilian control. Individual and women’s rights are protected; so are minority linguistic, educational, and religious rights. The federation will be officially bilingual in Arabic and Kurdish. Islam is merely a source of legal inspiration, and its impact on law-making may be less than that phrase suggests if judges and law-makers closely follow the most reasonable reading of the text. The Law recognizes the deep diversity of Iraq’s nationalities and sects: Iraq is no longer defined as an Arab nation. Kurdistan is, at last, officially recognized as a region, and in effect as a nation.

The Law promises federation. The voters of Kurdistan (and in any three “governorates”) have a veto over the ratification of the permanent constitution. Critics of this provision, in Iraq and abroad, fail to recognize that federation and democracy (“majority rule”) are not identical notions, and that voluntary ratification by the prospective federative entities is critical in making a durable federation.

The Law addresses the deeply controversial final status of oil-rich and ethnically contested Kirkuk. The process stipulated to resolve Saddam’s expulsions, appropriations, and demographic engineering is fair. It can work. It builds in United Nations arbitration if the parties cannot agree. Mark this down as the test case for future conflict-resolution after the United States and its allies restore sovereignty to Iraq this summer.

The specified target of at least 25 percent female participation in the future federal assembly has received a great deal of attention as a progressive measure. But it is not only good for women; it is also good for pluralist politics. Provided there is coherence in the drafting of the electoral law (which is the next phase in constitution-building), the female target requires that a proportional-representation electoral system be adopted—though it leaves open the issue of which one will be selected. That is because other electoral systems cannot guarantee the female participation target without violating the Bill of Rights. In the backward system of democracy used in the United Kingdom’s Westminster Parliament or the U.S. House of Representatives, elections are fought under a winner-takes-all system in single-member districts. To achieve the female target in such a system would require one quarter of the districts to be fought as women-only contests—which judges would rule as contrary to the Bill of Rights. The adoption of proportional representation matters because it will dramatically reduce the prospects of one-party domination, or of domination by a Shi’a or an Arab party in the first federal assembly election—which will also function as a constitutional convention.

There are, of course, problems with the Transitional Law, apart from the fact that some so-far-unelected Shi’a ayatollahs want majoritarian control—that is, to put democracy ahead of both liberty and federation, and their community ahead of others. Four problems will become apparent.

First, the Arab negotiators and the American lawyers who drove them wanted an overly centralized federation, even in Arab Iraq. Federal judicial supremacy, a federal monopoly on natural resources, and federal preponderance in both monetary and fiscal policy jointly recreate the dangers of a rentier-oil despotism. These powers threaten to prevent well-run regions from flourishing. They will tempt a federal majority to impose its economic, religious, and cultural preferences on others. Kurdistan works; the point should be to let the rest of Iraq reach its standards, rather than to impose foolish uniformity.

Second, the executive institutions may need reform. There is nothing to ensure that the federal cabinet is representative of Iraq’s diversity. The presidency is too weak, and the Prime Minister has too much power, especially if a strong Arab Shi’a party emerges. The three-person presidential council is a good idea. But the election of the three presidents on a common slate that must have the support of two thirds of the federal assembly creates problems. Obtaining the necessary support may be difficult. The election of one Kurd is not assured.

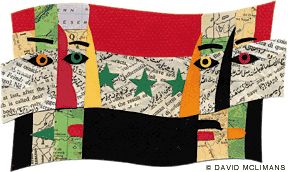

Third, the sketched federation is an uncertain compromise between those who wanted a “non-ethnic federation” (in which the dominant fiction would be that all are “just Iraqis”) and those who wanted a “pluri-national federation.” Iraq’s integrationists wanted a majoritarian, centralized federation built around one nation. They wanted to use Saddam’s “governorates” (provinces) to undermine the integrity of Kurdistan, and to prevent “Sunnistan” or “Shi’astan.” Iraq’s pluralists, by contrast, wanted a federation supported by all its nationalities, not just Arabs. The Law is a draw between these positions. The design of the federal second chamber, the senate, will provide a new battleground for these rival visions.

Lastly, Kurdistan’s right to have its own police and internal security means that it may be able to transform its peshmerga into a Kurdistan National Guard. This prudent insurance against the recurrence of genocidal mistreatment by Baghdad-based forces will be criticized, but Kurdistan is not willing to sacrifice its security for promises.

So, the Law is a compromise between a centralized federation and a pluri-national federation. Like Janus, it has two faces. “But it is a start.” “A long journey starts with a single step.” “Everyone got something; nobody got everything.” These were the considered views of the negotiators. When the U.N. returns, as it should this summer, it should not encourage any unraveling of the interim constitution. That would lead to utter chaos.

To forestall that chaos—sought by al-Qaeda and its network—work is being done that is at least as important as America’s still-uncertain and occasionally foolish security policy. I am delighted to report as I end this letter that two conferences have just been completed here in Kurdistan. One was an Arab-Kurdish Dialogue; the other a Reconciliation Conference, hosted by Masoud Barzani. The Reconciliation Conference brought together enormous delegations from all nationalities, languages, religions, and sects, and included ex-Ba’athists (those who had not been involved in human-rights abuses). After a heated opening it ended rather well. It might be a portent of a broader constitutional conciliation, although it would be premature to assume that Kurdistan and Iraq are secured in a federal and democratic embrace. Many crises remain to be navigated, but it would be churlish not to call for two cheers for the Transitional Law.

—Brendan O’Leary