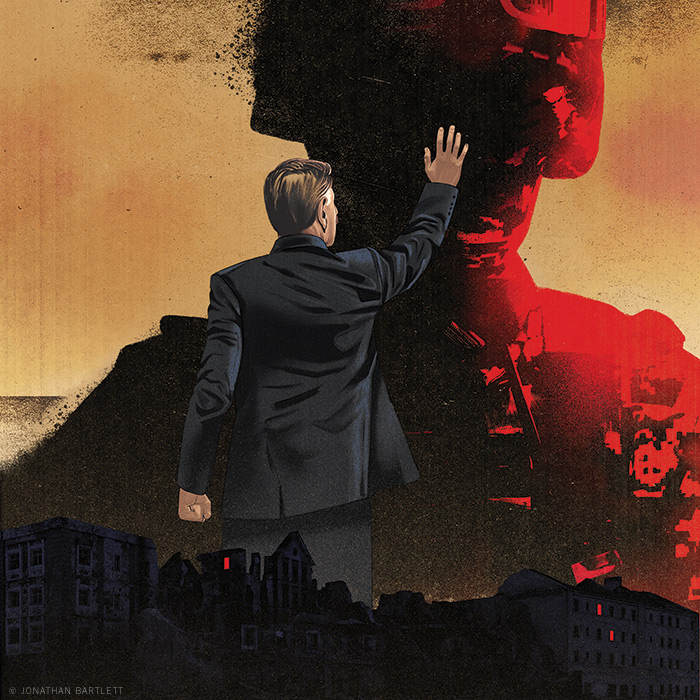

The Justice Department veteran who tracked down Nazis has a new—and possibly last—mission targeting war criminals in Ukraine.

If this were a movie, the scene would write itself.

After nearly four decades pursuing Nazi perpetrators and other war criminals for the US Department of Justice, Eli M. Rosenbaum W’76 WG’77 [“In Pursuit of Justice,” Mar|Apr 2017] was preparing for a well-earned retirement. For years the work had been virtually nonstop, a marathon with the urgency of a sprint, powered by the need to locate and prosecute the guilty before they died. Now, finally, Rosenbaum was looking forward to traveling with his wife and reconnecting with friends and family.

Then, one evening in mid-June, Attorney General Merrick B. Garland called, requesting that he stay on for one final mission.

“Life is what happens while you’re making other plans, right?” Rosenbaum, director of the DOJ’s Human Rights Enforcement Strategy and Policy since 2010, says. “And this is a classic example.”

When Rosenbaum answered the phone, Garland asked him to lead the Justice Department’s efforts to investigate war crimes in Ukraine, where reported atrocities against civilians by Russian troops have included bombings, torture, rape, and murder. “I was double gob-smacked,” says Rosenbaum. But he quickly assented to the one-year commitment. “People are dying. What more important thing could I do?”

A week later, as the newly appointed Counselor for War Crimes Accountability, Rosenbaum found himself in the western Ukrainian border town of Krakovets, meeting with Ukrainian prosecutors. “Whatever hesitation I might have had about whether I should be doing this work completely dissipated,” he says. “Seeing the determination of our Ukrainian colleagues to pursue justice even while their country was being decimated by cruel Russian Federation attacks was beyond inspiring.” He gained further inspiration, he says, from a mid-July conference on accountability for Ukrainian war crimes held in The Hague, in the Netherlands.

Rosenbaum, known for his prodigious work ethic and meticulousness, will be directing US activities on two fronts: investigating the still-small number of cases involving American citizens, over which the US has jurisdiction, and providing operational and legal assistance to Ukrainian and other European prosecutors in potentially thousands of other instances. In September, Garland and Ukrainian Prosecutor General Andriy Kostin signed an agreement to facilitate and expand the two countries’ cooperation.

Rosenbaum’s mandate will widen further if Congress succeeds in passing the Justice for Victims of War Crimes Act, which has bipartisan support. It would permit prosecution of war crimes committed by anyone found in the United States, even if neither the alleged perpetrator nor the alleged victim is an American citizen. On September 28, Rosenbaum testified in favor of the legislation before the Senate Judiciary Committee, saying it would address gaps in the law that had caused him and his colleagues “deep frustration.”

In his new position, Rosenbaum, assisted by lead prosecutor Christian Levesque and others in the Justice Department, will draw on a deep well of experience.

The first high-profile case that Rosenbaum directed for the DOJ’s Office of Special Investigations (OSI) was against the former Nazi rocket scientist Arthur L. Rudolph, who led the development of the US rocket that put a man on the moon. Rosenbaum marshaled evidence of Rudolph’s responsibility for the suffering and death of enslaved concentration camp workers during World War II. In a 1984 deal with OSI, Rudolph renounced his US citizenship and returned to Germany.

Even during a four-year break from the Justice Department in the mid-1980s, Rosenbaum, the son of German Jewish refugees and a Harvard Law School graduate, couldn’t look away. As general counsel of the World Jewish Congress, he investigated former UN Secretary General and Austrian presidential candidate Kurt Waldheim, who had covered up his wartime Nazi associations and activities. Waldheim won the presidency but was barred from the United States.

Returning to OSI, which he would later head, Rosenbaum helped resolve its most notorious case, involving John Demjanjuk. The Cleveland autoworker had earlier been misidentified by witnesses as the Treblinka concentration camp guard “Ivan the Terrible,” an embarrassing mistake. But it turned out that Demjanjuk was no innocent; he had served as a guard at another Nazi death camp, Sobibor. Rosenbaum secured his denaturalization and deportation to Germany, where in 2011 he was convicted by a Munich court.

So intense is Rosenbaum’s focus that even his hobbies are work-related. Over the years he has assembled a massive collection of rare books, letters, photographs, and other memorabilia centered on what he calls “accountability efforts in the wake of the Holocaust.” Among his thousands of treasures is a copy of the first published excerpt of Anne Frank’s diary, from 1946, signed by one of her childhood friends.

He also owns the original Israeli police transcripts of the interrogation of Adolf Eichmann, one of the organizers of the Holocaust. The six-volume set is signed by key participants in the case that led to Eichmann’s 1962 execution, including the Mossad agent who captured Eichmann in Argentina, the presiding judge at his trial, and Holocaust survivors who pursued him or testified against him.

Rosenbaum generally dislikes the sobriquet “Nazi hunter,” which he finds reductive and overly heroic sounding. But he had no objection to the New York Times print headline announcing his new position, “US Taps a Hunter of Ex-Nazis to Help Ukraine Track Russian War Criminals,” because “a big part of what I’ve been doing is deterrence messaging.”

To prospective perpetrators in Ukraine, Rosenbaum offers this warning: “If you dare to even think about obeying a criminal order, understand we’re coming for you. We came after Nazis, however long it took. It took over 50 years sometimes.” Even if it requires decades, he says, “we’ll still be looking for you.”

As an example of his persistence, Rosenbaum cites his office’s most recent Nazi case. It involved the deportation to Germany in February 2021 of Friedrich Karl Berger, a 95-year-old German accused of guarding concentration camp prisoners and presiding over a death march. That case rested, in part, on the recovery of waterlogged records from a German ship that had been sunk by the British during World War II. As is common, Germany declined to prosecute Berger—“one of the frustrations of the job,” Rosenbaum says.

In Ukraine, as in the Nazi cases, “we’re proving crimes that took place in Europe,” Rosenbaum says. But the differences are significant. In the Nazi cases, the “evidentiary trail had grown cold” but often included troves of captured Nazi documents, Rosenbaum says. In Ukraine, cases are more likely to rely on witnesses, electronic communications, and sophisticated techniques such as geofencing, which can pinpoint cellphone signals. And, while postwar German governments were generally cooperative, Rosenbaum knows that he can’t count on assistance from the current Russian government.

“What is primarily different here, and what makes this the most urgent work I’ve ever done,” says Rosenbaum, “is that the crimes are ongoing. This is the first time I’ve ever worked on a matter where the core international crimes are being committed while we’re doing the work.”

But Rosenbaum, who in recent years has pursued perpetrators from Guatemala, Bosnia, Rwanda, and elsewhere, stresses that he is no stranger to urgency. “I’ve always felt my work was rather like being told, ‘Run a mile in four minutes.’ And then you get a year older, and they say, ‘Well, now you’ve got to run it in 3:55, because these Nazis are dying.’ And then each year, you have to run it faster and faster and faster, even though you yourself are getting less able to run faster.”

In the case of Ukraine, Rosenbaum says, “almost contrary to logic, time is our friend. No government lasts forever. One day, as happened in Germany, a new [Russian] government may be empowered that is responsible and appreciates the importance of seeking justice in these cases. And we could gain access to evidence in Russia.”

Over time, too, perpetrators could end up immigrating to the United States, just as many Nazis managed to do. Even if prosecuting them specifically for war crimes isn’t feasible, Rosenbaum says, “we have a lot of experience in using other tools,” such as proving immigration or naturalization fraud. “Participants in the perpetration of these ghastly crimes need to know that they will more or less be stuck in Russia for the rest of their lives because they can never be confident that any other country is going to be safe.”

Since the Russian invasion, allegations of Russian military atrocities against Ukrainian civilians in places such as Bucha and Mariupol have dominated the news. But Rosenbaum says he would not shrink from cases involving Ukrainian perpetrators if evidence pointed in that direction. “I’ve worked with Russians before,” he says. “It’s a strange world.”

Along with their legal savvy, Rosenbaum says, he and his colleagues “also have a certain fearlessness. The word ‘impossible’ doesn’t scare us too much. We’re impatient in that we want to pursue justice as expeditiously as can be done. But if patience is required, we have that.

“I couldn’t think of anything that I would rather do than this,” Rosenbaum concludes. Then he signs off for a Zoom meeting with Ukrainian prosecutors in Kyiv.

—Julia M. Klein