A new look at a sensational old murder.

By Maureen Corrigan

FOR THE THRILL OF IT:

Leopold, Loeb, and the Murder

That Shocked Chicago

Simon Baatz G’81 Gr’86

Harper, 2008. $27.95.

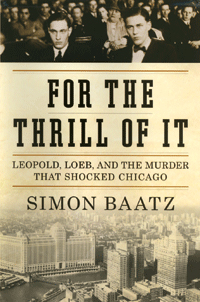

There’s a black-and-white photograph in the final chapter of Simon Baatz’s new book on the Leopold and Loeb murder that conveys the enduring weirdness of what is certainly one of the most inexplicable crimes ever committed. Captioned “The Happy Couple,” the photo shows a 60-ish Nathan Leopold sitting beside his wife of three years, Trudi Feldman, at a press conference in Chicago in 1964. (His wife? Is there no man so depraved that some dame out there doesn’t think he’ll do as marriage material?) The drowsy, business-suited Leopold in this photo bears no resemblance to the 19-year-old monster who, in the spring of 1924, conspired with his friend and lover, Richard Loeb, to snatch 14-year-old Bobby Franks off the streets of Chicago. In their rented car, Leopold and Loeb (separately and together) proceeded to bludgeon Franks with a chisel, jam a rag down his throat and tape his mouth shut, stop for hot dogs while Franks’ corpse lay crumpled on the floor of the car, pour chemicals over his face and genitals, and leave him to rot in a drainage ditch while they coolly proceeded with their plan to collect ransom money from the boy’s frantic family.

Back then, Leopold thought he was one of Nietzsche’s “supermen,” an uber-intellectual above the laws of mere mortals. After all, he had sailed through college and, like Loeb, was pursuing graduate studies at the University of Chicago. (Both boys were the scions of wealthy and cultured Jewish families.) Leopold and Loeb might well have pulled off the “perfect crime” had it not been for a specially crafted pair of tortoiseshell glasses that Leopold accidentally dropped at the crime scene.

After his arrest, Leopold bragged to a reporter: “A thirst for knowledge is highly commendable, no matter what extreme pain or injury it may inflict upon others.” How does one reconcile this impression of Leopold as a reptilian predator to that of the image four decades later in which he’s rendered middle-aged, married, and mundane? (Of the two, Trudi looks the more likely candidate to murder in cold blood. Her eyes, above a spasm of a smile, are as blank as bullet holes.)

Was Franks’ murder an act of freakish free will borne of intellectual hubris? A cautionary example of the dangers of reading pulp fiction? (Loeb was a crime-story aficionado.) An inevitable consequence of the godless, libertine Roaring Twenties? The end product of indifferent parenting and faulty endocrine glands? All these theories had their champions, and yet none, then or now, adequately accounts for the random strike of pure evil that was the Leopold and Loeb case.

In his engrossing book, For the Thrill of It: Leopold, Loeb, and the Murder That Shocked Chicago, Simon Baatz (who earned a Ph.D. in the history of science from Penn and teaches at John Jay College of Criminal Justice as well as at the Graduate Center, City University of New York) explores the question of why-they-dun-it, but he’s even more fascinated by the trial of Leopold and Loeb, during which an epic argument ensued over two opposing theories of crime and punishment. Indeed, it’s a triumph of Baatz’s book that he’s able to render the trial so suspensefully that it more than holds its own as a narrative alongside the account of Franks’ murder, which has an undeniably sinister power (as Alfred Hitchcock recognized in Rope, his classic film inspired by the Leopold and Loeb case).

The duo’s guilt was never at issue. With a disturbing lack of affect, the young men explained to reporters about how they randomly chose their victim, who happened to be walking down the street after school one day, enticed him into their car (it “helped” that Franks was Loeb’s cousin), and murdered him as if it were a simple matter of stepping on a cricket. What was at issue was how human ciphers like Leopold and Loeb should be judged.

In a packed Chicago courtroom throughout the summer of 1924, two lawyers—one a living legend—faced off. Arguing for the prosecution, State’s Attorney Robert Crowe spoke on behalf of time-honored notions of individual responsibility and retribution. The defense attorney, the renowned Clarence Darrow, had been swayed in the years following World War I by scientific revelations about the power of animal instinct and hormones in humans.

Darrow came to dismiss the notion of free will and, instead, embraced biological determinism as the root cause of human action. In his 1922 book, Crime: Its Cause and Treatment, he wrote: “That man is the product of heredity and environment and that he acts as his machine responds to outside stimuli and nothing else, seem amply proven by the evolution and history of man … Chance, accident and whim have been banished from the physical world.” If humans were not responsible for their actions, Darrow reasoned, what was the point of punishment?

Particularly capital punishment. The parents of Leopold and Loeb wanted to save them from the death penalty, and entreated Darrow to take on the case. Darrow, ever the big-stakes player, agreed. He was eager to publicize his theories of criminology and determined to resuscitate his reputation after the fiasco of defending the McNamara brothers in 1911 against charges that they had bombed the building that housed the rabidly anti-union Los Angeles Times. (The McNamara brothers eventually pled guilty and Darrow was reviled as a con man by union members across the land who had raised funds for the brothers’ defense. A just-published book called American Lightning by reporter Howard Blum recounts the case, making this a banner season for Clarence Darrow in nonfiction.) Baatz details the brilliant strategies by which Darrow managed to sidestep a trial by jury for Leopold and Loeb and walks readers through the crucial testimonies of mental-health experts of the time.

Ultimately, the parents of Leopold and Loeb got their wish. On the morning of September 10, most of Chicago listened to the live radio broadcast from the courtroom in which Judge John Caverly sentenced the pair to life imprisonment. While Leopold, as noted earlier, went on to enjoy marital domesticity, Loeb was murdered in prison in 1936. A grief-stricken Leopold washed his body.

“The Happy Couple.” Long before Nathan and Trudi, there was “The Happy Couple” of Nathan and Richard. In For the Thrill of It, Baatz substantively delves into the two men’s upbringing, their symbiotic sexual fantasies, and the medical exams taken during the trial that measured their metabolic rates and organ health. But for all the light Baatz shines on this case, posterity will always confer the same verdict on Leopold and Loeb: Unknowable.

Maureen Corrigan Gr’88 teaches literature at Georgetown University and is the book critic for National Public Radio’s Fresh Air.