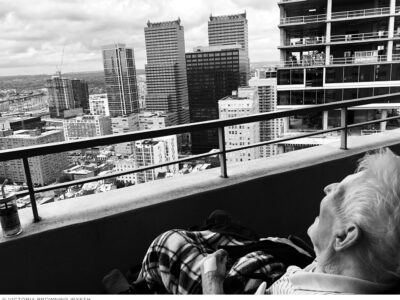

Illustration ©Daniel Chang

Penn Humanities Forum | The subjects were given a simple task of identifying letters and symbols that flashed ever faster on a computer screen. Those who were retested hours later showed no improvement in their scores. But test-takers who came back the next day after a full night’s sleep were able to process the images 20 percent faster.

“Something has changed in your brain while you’ve slept to make you better able to perform these tests,” said Dr. Robert Stickgold, a professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, in a lecture titled, “Sleep, Memory, and Dreams,” sponsored by the Penn Humanities Forum in October.

In contrast, subjects who pulled all-nighters fared no better than they did during their initial testing, he said. In fact, even if they caught up on their sleep during the following two nights, all the “training” benefits from that first day were lost.

Similar performance differences were found in tasks that involved typing number sequences, determining the rules in a probability game, and figuring out the next number in a series.

On some level, Stickgold predicted, sleep may be as important for test performance as studying. “And that doesn’t speak well for college students, who practice what I refer to as sleep bulimia, which is a binge-purge process. They will go during the week on four hours of sleep [a night]. Then they get to the weekend, sleep 10 to 12 hours a night, and wake up Monday morning say[ing], ‘I feel fine again. Everything’s OK.’ But with all those short nights, they’re shortchanging themselves,” he says. “Your brain is doing your work for you during the night in a way that you can’t do when you’re awake.”

One group who appear not to benefit from sleeping on a problem are schizophrenics. “Whatever this process is that allows us to improve overnight with sleep is completely dysfunctional with these patients,” Stickgold said. More study is needed to find out why this happens. “We see the same phenomenon with cocaine addicts when they’re withdrawn from their drug. That may be part of the reason they’re driven back into using the drug again, so that they can feel that their brain is processing information the way they’re used to.”

Stickgold also looked at the function played by different stages of sleep. Subjects woken up in the middle of REM sleep, for example, do better on tests that require them to form quick associations between weakly related word pairs, suggesting that this sleep stage may help fuel human creativity.

“Finding novel solutions to problems, finding ways that the world fits together that you’ve never seen before, might turn out to be a major function of REM sleep.”

Each sleep stage may play a unique role in the processing of memories from the day before, Stickgold said. After playing a skiing simulation game called Alpine Racer, subjects were woken up each time they started to fall asleep for the first 45 minutes. Most reported seeing specific skiing images at sleep onset. It might be that “this replay of recent memories tags them for subsequent processing later in the night.”

Another group of game players was allowed to sleep for two hours before being awakened. This time, none reported direct skiing images in their dreams. But they made comments such as, “I dreamt I was falling down a hill.”

“It’s as if the brain is moving one step further in its association chain,” he said. In its attempt to make meaning out of experiences, the brain “is looking through a much wider network.”

“Sleep actually consolidates and enhances memories and alters associative memory processes to make deeper associations more accessible. Through sleep we find patterns in our daily experiences. And dreams might be part of that story.”—S.F.