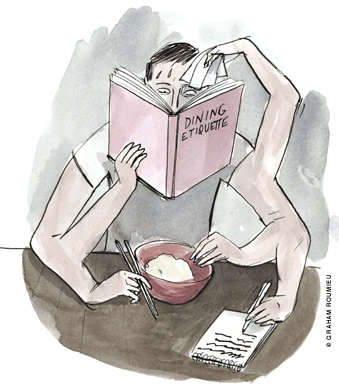

Teaching an anthropologist how to eat.

By Carl Hoffman

I suppose it was my father’s fault. He was the one who used to browse through Boston’s secondhand bookstores and bring home stacks of old National Geographic magazines. And I, then no more than six years old, was the one who would find them piled up in the living room and become enthralled with pictures of Masai warriors spearing lions in Kenya, Pygmies of the Congo’s Ituri Forest posing with their bows and arrows, and Indians of the Amazon proudly displaying their collection of shrunken heads. For an impressionable kid growing up in a down-at-heels, working-class Jewish neighborhood in one of Boston’s old streetcar suburbs, those pictures were irresistible. They all but ensured that I was destined to declare anthropology as my major on my very first day of college.

It was thus that I found myself deep in the dark, howling jungles of Borneo in Indonesia several years later, at the start of fieldwork for a Ph.D. in anthropology from Penn, searching for members of an elusive, seldom-seen tribe of forest people known as the Punan. I, the ultimate urbanite—who had never so much as gone camping—was now flitting through the rainforest with two native guides, under a thick tree canopy that barely let in sunlight.

After several days of stumbling through the jungle, being rained on, devoured by insects, and attacked by a malevolent host of bloodsucking leeches, we suddenly made contact. Out of the green darkness stepped a man almost totally naked except for a loincloth, a bead necklace, and what appeared to be an animal’s tooth in his upper left ear. He held a blowgun; a rattan belt around his waist held a bamboo container with poison darts. Moments later, a woman materialized—also naked save for a bead necklace, bracelets, and anklets. The man pursed his lips and produced a long, low trilling whistle, which caused two more people to emerge from the trees—both of them small boys under the age of 10. And thus we stood, in a tiny clearing in the midst of the jungle, all of us gaping in wonder. The Punan, including the woman, were lithe and well-muscled. Their hair was matted and dirty, their faces streaked with grime, their unwashed bodies criss-crossed with a thousand cuts, scratches, and scars acquired from life in a merciless, unforgiving environment. After a terse exchange of words with my guides, the little family of the forest invited me home for lunch.

They led us through the woods for about 15 minutes, until we came to a small bamboo lean-to, roofed over with a moldy, bug-infested thatch. This was the family’s home. I eased myself into their dwelling, praying that I wouldn’t fall through the fragile bamboo and rattan floor. My host rummaged around behind the house and produced a large earthenware Chinese jar, with a dragon figure in bas relief near the rim—one of thousands of such jars scattered across Southeast Asia, relics of ancient trade with Ming Dynasty China. He removed a makeshift cover, plunged his arm into the jar, and extracted a huge, dripping handful of something that looked like … well … something like phlegm. This loose, slimy substance oozed off of his hand and onto a large leaf. Two more plunges into the jar, two more dripping handfuls of this awful looking stuff, and then the leaf with its quivering light-gray slop was ceremoniously placed before me, with hearty invitations to dine. While everyone else was being served, my guides explained that we were about to partake of rendered pig fat, melted months—perhaps years—ago off of the flesh of wild boars. Along with a few pieces of flesh and gristle, this hunter’s bounty was usually set aside and reserved for just such high social occasions as this.

I was young. I was adventurous. I began to eat the rancid pig fat. Tentatively at first, I sampled one or two tastes with the tip of one forefinger. Then, determined to show my hosts how much I appreciated their hospitality—or perhaps just wanting to be finished with this as quickly as possible—I began to shovel the pig fat into my mouth with almost deranged abandon, one slimy handful after another. Before I knew it, pig fat was everywhere—all over my face, in my beard, on my shirt, in my lap, and all across the floor. Slowly I became aware that my jungle hosts and guides were staring at me with what could only be described as arch disapproval. I asked what was wrong, to which my guide replied with a withering sneer, “You’re kind of messy, aren’t you?” I then realized, with growing embarrassment, that despite their remoteness and apparent dishabille, these “primitive” people of the rainforest had notions of dining etiquette as strict as anyone else’s, and that I had oafishly flouted them.

My next display of gaucherie occurred some months later on the Indonesian island of Java, where I was recovering from several grueling months on Borneo. I had been holed up in a quiet student dormitory in the ancient city of Jogjakarta, when one of my housemates—a young Javanese medical student—decided to go home to his village for a visit with his family and invited me to come along. After a five-hour ride on a train so crowded I was able to sleep comfortably standing up—followed by a bone-wracking hour over bumpy, unpaved roads in a rickety horse-drawn cart—we reached a small cluster of houses and gardens set amid verdant rice paddies and groves of coconut palms. Immediately upon our arrival, the sleepy little village sprang into action and feted us with a resplendent welcome dinner. Huge mounds of boiled white rice were surrounded by numerous small side dishes of meat and vegetables—cooked sweet and spicy in the style of central Java and served without silverware, to be eaten by hand.

Maybe I was exhausted from the journey. Perhaps I was excited to be in a real Javanese village, suffused with its rich, unspoiled, authentic culture. I might simply have been distracted by the exquisitely beautiful Javanese girls who had gathered with the crowd to welcome us. Or maybe I was just very hungry. There had to have been a reason—a good, compelling reason—for me to have then committed one of the most idiotic social faux pas of my life. With complete disregard for everything I had read, heard, and been taught about this part of the world by Penn’s graduate faculty of anthropology, I sat down to dinner with my friend and his family, smiled pleasantly, thanked my hosts profusely for their gracious hospitality, and began to eat with my left hand. Into the nearest mound of steaming, pure white rice—as well as into each and every succulent little side dish—went my dominant, eager, grasping left hand. How could I have forgotten that virtually everywhere in South and Southeast Asia, the right hand is used for touching people, giving and receiving things, writing, cooking and eating—while the left hand is ingloriously reserved for cleaning oneself after going to the toilet? Even now, more than a quarter of a century later, I can still see the looks of utter shock on the faces of my bewildered hosts.

My third lesson in table manners came four years later in the Philippines, on the island of Mindoro, high up in the mountains with a very remote hill tribe known as the Hanuno’o. Still very traditional, these people lived in sturdy little houses of bamboo, wove their own cotton and dyed it blue with native indigo, composed songs and poetry and made music on traditional homemade string-instruments, wrote poetry and messages to each other on bamboo in their own ancient native script, filed their teeth and chewed betel nut, and lived much as their ancestors had. It was my privilege to dwell among them and share their wonderful lives for better than three years.

The life of this tribe revolved around the annual planting and harvesting of their own native strains of upland rice, which they sowed on steep, misty hillsides that were nurtured by tropical sunshine and fed by monsoon rains. The Hanuno’o were generally rather laid-back—gentle, peaceful, and easy-going to a fault, except about anything concerning their rice. I was told, “Our rice is sacred. It has come down to us from our forefathers. As long as we respect and cherish it, it will come to us in abundance every year.”

This respect was expressed in the rituals that accompanied planting rice, the festivities that went along with harvesting it, and the reverence they felt when eating it. Unlike the Javanese, the Hanuno’o didn’t care a feather or a fig which hand one used to eat their rice, but they were very strict about the direction in which the rice moved around one’s plate. Barely a week after my arrival, a very pretty, charming, vivacious, sexy, and, unfortunately, married young woman named Oo-ming was assigned by the village elders to teach me how to eat. “You must never give the rice the impression you don’t respect it,” she solemnly told me in her soft, sweet voice. “You must never let so much as a single grain fall from the edge of your plate. Never make a motion that might be interpreted as pushing rice away from you. Always, always pull the rice toward you. Start taking your handfuls of rice from the outer edges of your plate, and constantly pull the rest of the rice toward you, toward you, always toward you, until you have finished the very last handful.”

It has been more than 25 years since anyone has offered me pig fat, but I must admit that I am still somewhat messy. And after leaving Java I gradually reverted to eating with my left hand. Fortunately, no one here in Israel seems to mind. But for some reason the etiquette I acquired among the Hanuno’o has stayed with me throughout the years. I continue to eat rice—all rice, even Uncle Ben’s—exactly as I was taught to do by a beautiful girl named Oo-ming.

Carl Hoffman G’76 Gr’83 is a Tel-Aviv based freelance writer whose articles appear regularly in the Jerusalem Post, and sporadically elsewhere. Formerly of Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Indonesia, and the Philippines, he has lived in Israel since 1997 with his wife and two children.