Class of ’95 | It’s known in some circles as the Plastic Vortex, and it’s roughly three times the size of the continental United States. Oceanographers know it as the North Pacific Gyre, and among other things it’s a convergence zone for marine debris. Much of that flotsam is plastic, spewed from land into streams and rivers and eventually making its way into the oceans—where, thanks to its non-biodegradable nature, it becomes a more or less permanent part of the seascape.

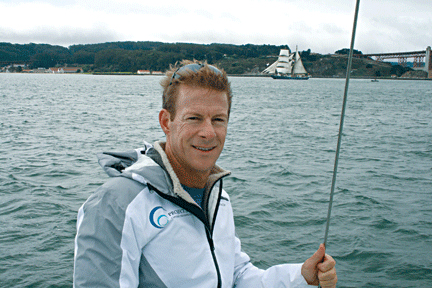

Sailing into that vortex is Doug Woodring WG’95, the co-founder and director of Project Kaisei, a nonprofit organization based in San Francisco and Hong Kong. Project Kaisei’s slogan is “Capturing the Plastic Vortex,” and its stated goal is to “increase the understanding of the scale of marine debris, its impact on the ocean environment, how best to prevent future waste, and how to accelerate efforts to clean up this vast and growing challenge.”

For Woodring, the fact that it’s a tall order is part of its appeal.

“We’re not trying to be overly sensationalist, but we need to draw awareness to the problem,” he says. “And it is a huge problem. The estimates are that there are millions of tons of plastics out there; it’s just dispersed over a very big area. With UV [ultraviolet] degradation, the plastics break down into very small bits. So it’s like this soup out there, and the smaller the bits, the easier they are to be ingested into the food chain.”

This past August, Project Kaisei collaborated with the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC-San Diego, funded by a raft of sponsors. It sent two research vessels—the tall ship Kaisei (Japanese for “Ocean Planet”) and Scripps’ New Horizon—to study the Gyre’s swelling accumulation of plastic, as well as “possible retrieval and processing techniques that could be potentially employed to detoxify and recycle these materials into fuel.”

Woodring himself was aboard the New Horizon, and between it and the Kaisei they covered some 3,500 miles, studied debris and invasive species, and conducted more than 50 surface-debris sampling trawls as well as deep-water tests at different levels. While debris was recorded at every stage of the expedition, they documented a steady increase in trawl samples as the ship moved deeper into the Gyre, counting up to 400 visible pieces of plastic every half hour. They also found a wide range of invertebrates attached to the debris—swimming crabs, sea anemones, barnacles, sponges, algae—as well as some heavy metals and other toxins. Discarded fishing gear known as “ghost nets” sometimes contained long-dead sea life.

“I was always up on the watch looking for plastic,” says Woodring. “We were able to count the little white specks from two stories up to extrapolate from what the sample nets were showing. Our surface troll nets were only a meter wide, and in every troll net we got plastic—and we got it prolifically.”

The problem requires a two-pronged solution, he says. One is the “capture” side—removing the debris from the water. The other is remediation—figuring out what to do with the plastic once it’s been removed. The technology to convert plastic to diesel fuel now exists, and while the wide range of colors and thicknesses—not to mention the logistics of collecting it—presents a big challenge for recyclers, it can be done. That, Woodring points out, could then “drive the economic chain of incentives to gather this material and take it to someone who’s going to make fuel from it.” An island nation like the Philippines, he suggests, could profit considerably.

The trick now is to get all of the potentially interested parties—entrepreneurs, inventors, legislators, manufacturers, and consumers—on the same page. “We’re close,” he says.

One “neat” example of the change they’re starting to effect involves the ghost nets that are lost at sea or cut off by fishing boats, and which kill marine life and damage ship propellers. Woodring and his colleagues collected a number of them and sent them to South Korea to be melted and woven into clothing.

Project Kaisei has been selected as a Climate Hero by the United Nations Environmental Program, and this summer it will launch a second expedition to the North Pacific Gyre, sending several vessels to continue the marine-debris research and test a variety of collection systems. “We also have some studies on land that we want to do with industry,” Woodring notes, which would examine the “best hopes in the recycling or remediating area for plastics and what new materials are coming out, so we can really get things to market much faster.”

The Hong Kong-based Woodring, who has worked in Asia for the better part of two decades and whose worldview has long encompassed the Far East and environmental issues, admits to being “excited about bringing Asia into this whole discussion.” He has a dual masters degree from Wharton (where he co-founded the Wharton Asia Business Conference) and Johns Hopkins’ School of Advanced International Studies, where one of his sub-majors was environmental economics. For the past two years he has been chairman of the Hong Kong Chamber of Commerce’s environmental committee, and has served as a consultant for such environmental-technology companies as Verte Asia, which specializes in “living vertical green walls.”

He traces his involvement to growing up in California and having access to so much relatively clean water. China, whose extraordinary economic growth has come at the expense of the environment, was a shock to his system—and a spark.

“I’ve always had it in my head that this was going to be a very substantial area for opportunities,” Woodring says. “Without that innovation technology, you don’t get that change in environmental issues. You’ve got to get people thinking in a different way—that something can be not just a cost, a burden on the economy. It can be a driver.

“This is an exciting project, because we’re building a global collaboration of science, innovation, remediation, new materials, education, and outreach to help bring our oceans back to health,” he adds. And there’s no shortage of the not-so-raw material in question.

“There’s so much plastic used on the planet. If you’re [looking for ways] to remediate that, recycle it, there’s opportunities.”

—S.H.