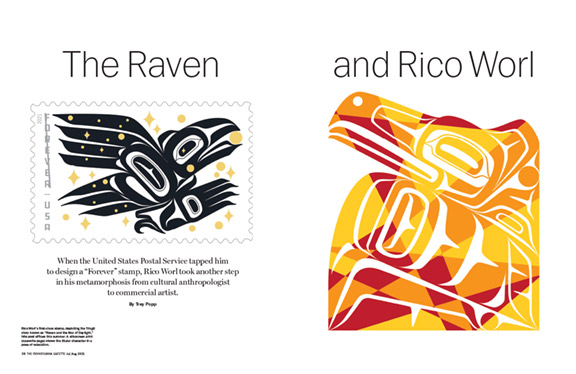

When the United States Postal Service tapped him to design a “Forever” stamp, Rico Worl took another step in his metamorphosis from cultural anthropologist to commercial artist.

By Trey Popp | Artwork by Rico Worl

As a kid growing up in Alaska, Rico Worl C’09 used to visit his maternal grandparents in Nenana, where about 400 souls lived beside the confluence of the Nenana and Tanana rivers midway between Fairbanks and Denali National Park. His favorite thing to do there was poke around his Grandpa Rudy’s woodworking shop. It was stuffed with meticulous scale models of cabins, food caches, fish traps, and other traditional artifacts of Athabascan material culture.

Worl was particularly fascinated by his grandfather’s fish wheels—miniaturized versions of the current-driven contraptions that indigenous peoples had adopted for subsistence salmon harvesting. These devices combined watermill-style paddles with netted baskets designed to scoop fish from a river and deposit them automatically into an integrated holding tank or box. Rudy sold his replicas to tourists. But the source of his craftmanship ran deeper.

“The models were just a side hustle,” Worl would later marvel. “Grandpa used to build these for real. Like put it on a river and feed his family. They literally grew up without money, so it was a vital source of livelihood for my mom and her siblings.” Worl’s uncle Chris recalled how they used to outfit the paddles with coffee cans that would splash water onto the caught fish to keep their gills moist and the flies at bay.

This past winter, at the urging of subscribers to his Patreon channel, Worl bundled up all these inspirations—the woodshop memories, a photo of one of Rudy’s fish wheel models, his uncle’s fishing stories—transformed them into a three-dimensional digital CAD model, and then distilled it all down to a peel-off sticker roughly the size of a US quarter.

As number 18 in a series of stickers that rarely exceed one inch in any direction, Worl’s fish wheel extended a theme that has dominated his adhesive oeuvre since his first edition, which depicted a jar of preserved salmon labeled with the name of his design firm, Trickster Company. Their minute measurements belie the density of meaning they contain.

“The first few were food,” Worl says, reflecting on the importance of products like seal oil and sea asparagus (other sticker subjects) among Indigenous Alaskan communities. Raised “modern-traditionally” by parents who were Tlingit on one side and Athabascan on the other, Worl frequently mines his cultural heritage for artistic inspiration. “There’s a certain pride we take in our subsistence food: there’s the pride of being able to acquire it, and more importantly being able to share it with our community. My sister and I both hunt,” he continues. “It was always this big deal to go and catch a seal, or get herring eggs, or catch some fish and bring it back and share it with other people in the community.”

Sticker number 19, fittingly, depicted a traditional halibut hook. “It’s a discussion piece about the ingenuity of Tlingit people,” Worl explains. “Because it’s probably a more efficient hook than any modern hook. It’s crafted in a way that the size and angle are specifically designed to catch the exact size halibut you need. You want smaller fish to keep getting bigger,” especially reproductive females. “And some fish are too big … So this hook is really a very targeted system: it lets you choose exactly the size of fish that you want to catch.

“There are so many different aspects” to the subsistence foodways he has celebrated in his stickers, he says. “It’s a means of social binding. It’s a source of wealth. It’s a healthier means of living than commercialized processed foods.”

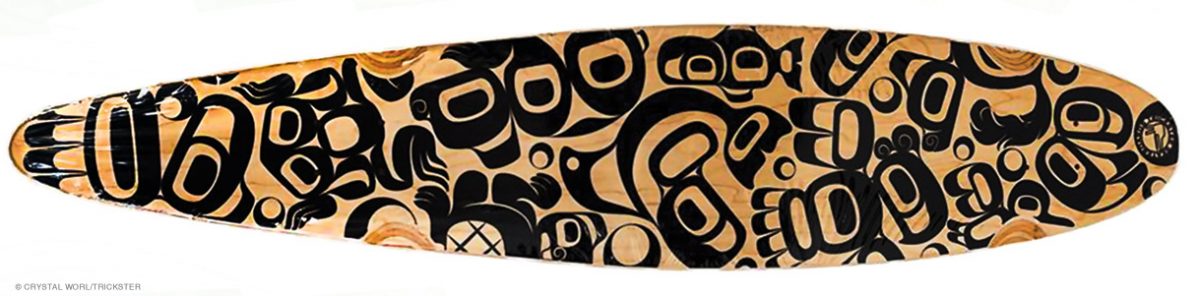

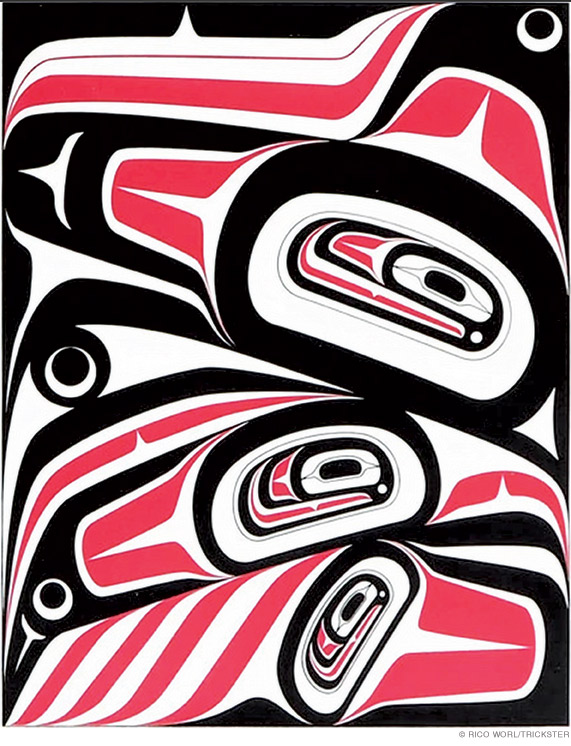

Trickster, which Worl founded with his sister Crystal in 2014, initially focused on sports equipment. Skateboards bearing Northwest Coast formline motifs—whose ovoid features and curvilinear abstractions are a signature of Tlingit and other artistic traditions among First Nations in Alaska—led to basketballs and yoga-related gear. Worl is drawn to play in various forms. One early product was a deck of playing cards bearing Tlingit designs and packaged with the story of Raven, a trickster character in Tlingit mythology. As culture conservation goes, Worl blends earnestness with whimsy. To honor Elizabeth Peratrovich, a Tlingit civil rights activist whose advocacy led to Alaska’s influential Anti-Discrimination Act of 1945, he made holographic stickers bearing her portrait in the style of a dollar bill.

A combination of happenstance, convenience, and certain notions about art affordability led Worl into the realm of tiny stickers. Before the pandemic he found himself traveling frequently between Alaska and Phoenix, where his fiancée was living. All the plane trips got him brainstorming about something that would be lighthearted, easy to carry, and sellable in pop-up stores. Trickster had for some time offered larger stickers as an “add-on product,” so Worl—who as a jeweler was already comfortable working in miniature—thought it would be fun to go sticky and small.

“Most people like stickers,” he laughs. “I don’t know why. There’s just some kind of universal draw to them. They are artwork that’s accessible to anybody—they’re super cheap. So anybody can pick up a sticker; if they appreciate an artist, they can have that little bit of artwork.” And it doesn’t take much work to find a place to stick it. “Your water bottle is full of stickers,” he notes, “but maybe there’s a tiny little corner for a one-inch sticker.”

At $1.50 to $4 a pop, they’re more of a creative lark than anything else. (Several editions double as Trickster branding, but most bear no trademarks.) But you could also look at them—and Rico Worl’s enthusiasm for tiny, sticky-backed art—another way. Because his miniature fish wheels, salmon jars, formline eagle motifs, and all the rest are also successors to his breakthrough public recognition as an artist: in July, the United States Postal Service will debut a “Forever” stamp he designed in homage to Tlingit culture.

Before he was approached by a USPS art director in the spring of 2018, Worl didn’t really think about himself as an artist. “I got my degree in anthropology,” he says, and that academic discipline persisted as the wellspring of his professional identity after college.

Before Worl came to Penn, he came to the Penn Museum. Drawn by a research exchange program designed to bring Native students to do anthropological research, he spent a semester there exploring the legacy of Louis Shotridge. Shotridge was a Tlingit anthropologist who worked as an assistant curator at the museum from 1915 to 1932, during which time he conducted three museum-sponsored expeditions. He collected some 400 artifacts for the museum’s collection. In the early 2000s the propriety of some of his purchases—and rightful ownership of the artifacts—was challenged by various Tlingit entities. Roughly one-third of Shotridge’s acquisitions were claimed for repatriation under the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) [“Gazetteer,” Mar|Apr 2011].

Partly because there is little doubt that at least some of these objects would have perished but for their original transfer to the Penn Museum, Shotridge left a complex legacy. “He was pretty bad at being a Tlingit,” in Worl’s off-the-cuff gloss, “but alright at being an anthropologist.”

Worl’s experience at the museum hooked him on the discipline. “Penn made an impression on me,” he says, “so the next year I applied, and I came as a student.”

Upon returning to Juneau after earning his bachelor’s degree, Worl dove right into the world of Indigenous culture preservation by way of a job with the Sealaska Heritage Institute, a nonprofit dedicated to the enhancement of Southeastern Alaska’s Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian cultures.

“I worked on a lot of things that had to do with the Native American Graves and Repatriation Act, getting things returned from museums to tribes,” he recalls. “There is, of course, a bit of a contentious relationship between Penn and Tlingit people, and I’d gotten to be right in the middle of that during my studies. Which was very educational.”

The work had a major upside. “I was always surrounded by very big pieces of Tlingit artwork, all the time,” he says. “I got to travel to museums and be around these pieces.”

Meanwhile, Worl found himself increasingly nettled by a dynamic that weighed heavily on the arts economy in contemporary Juneau. “Pre-COVID, we had over one million people a year coming through Juneau as tourists, spending millions of dollars” there and in southeast Alaska. “And a huge chunk of that was going toward knockoff Native art.

“That was really bugging me during the same time I was working on repatriation,” he recalls. He became engrossed by a new question: “How do we empower ourselves to return some of that market share back to the community that developed that artwork?” His search for solutions shifted his viewpoint away from research and toward creative design. “So that’s when I created one of the first products, which was the playing cards.”

The choice of playing cards as a vehicle for honoring an Indigenous culture invites multiple interpretations. Face cards and card backs are natural canvases that afford broad artistic latitude within well-defined limits. They are also, of course, a means by which many American tribes generate revenue through casino gambling—though not, it is significant to note, in Alaska. But at a more basic level, playing cards belong unambiguously to the world of commerce, rather than the rarified realm of art museums. And the same is true for the lion’s share of Rico Worl’s artistic output. (His silkscreen prints merit an exception.)

“We don’t really have a choice but to live in a capitalistic system,” he says. And when it comes to cultural renewal and vitality, the realm of commerce is where the rubber meets the road. Lest there be any doubt about that, consider the way USPS art director Antonio Alcalá discovered Worl to begin with. It happened at the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, DC—but not in the exhibition galleries. Alcalá noticed a Trickster basketball in the gift shop. (Basketball’s popularity among Native Americans dates back to the early 1900s, when certain American Indian schools in the Midwest developed a style of play whose fast tempo reportedly riveted the sport’s creator, James Naismith.)

“He was drawn,” Worl says, “to how we were working to represent our culture in a very modern way.”

“It was definitely a lot of pressure,” Worl says about being tapped to design a postage stamp. “I knew it was going to be a national platform,” and the relative rarity of Indigenous artists in the postal stamp program gave him a sense of responsibility. Cultural stewardship has been the driving pursuit of his adulthood, and suddenly he had a stage as extensive as the US mail network and as accessible as a nickel and two quarters. “Rather than focusing on creating a piece that represented me or my artwork, it was really about, how do I represent Tlingit art?”

It was the same question he had been answering for about five years via Trickster. As the company’s product lines have expanded to include men’s and women’s apparel, face masks, jewelry, cutting boards, and other home goods, Rico and Crystal Worl have become curators as well as creators, opening their marketplace to a select group of designers, illustrators, and authors. Their goal isn’t far from what originally drew Rico to the Penn Museum and anthropology: “to represent modern Indigenous lifestyle to a broader audience.”

He ended up choosing to depict the Raven character, using the characteristic formline style of Tlingit graphic art. “The image references a story that’s often referred to as ‘Raven and the Box of Daylight,’ or ‘Raven Steals the Sun, Moon, and Stars,’” he says. “That one is a foundational story, if you want to learn about Tlingit culture.”

The story’s particular resonance to Worl came out vividly in a blog post he wrote when the stamp design was unveiled last November. In an abbreviated rendition of the story, he described Raven as a canny shapeshifter bent on liberating the heavenly bodies from a chieftain who had sequestered them in boxes, keeping the world dim. Transforming himself into a pine needle, Raven contrived to be drunk in a glass of water by the chieftain’s daughter, who gave birth to the trickster nine months later.

“In the child’s youth he loved the boxes of family treasure which held the sun, the moon, and the stars,” Worl recounted. “He begged to play with them. With time, the grandfather could not say no any longer. Raven was allowed to play with the box of stars. Not long after, he freed the stars. Raven was in big trouble … He cried for forgiveness. After time he asked to play with the next box. Raven promised not to open the second box, but he did. The moon was free. Raven cried. He cried for forgiveness. A grandparent’s love is immeasurable. He let Raven play with the box of daylight.”

In this manner, Raven filled the universe with heavenly light.

“The stamp depicts a moment of climax in one of his heists,” Worl elaborated. “Raven is trying to grab as many stars as he can—some stuck in his feathers and in his hands or in his beak, some falling around him. It’s a frazzled moment of adrenaline. Partially still in human form”—as the stamp shows by way of a human hand—“he carries the stars away.

“I think it depicts a moment we all have experienced,” Worl wrote: “The cusp of failure and accomplishment.”