Endless forms most beautiful and bizarre.

In 1992, Steven Potashnick GD’78 came home from a downtown Chicago auction house hauling a 19th-century dental cabinet made of solid oak. It was a beautiful piece. There was no denying its elegant craftsmanship—and his wife Jo Ann didn’t try. She merely observed that her husband already owned one. And that antique dental cabinets take up quite a bit of room.

Steve had always been a collector—albeit a “somewhat scattered one,” by his own admission. Jo Ann, meanwhile, had “fully countenanced” his acquisitional urge. But spousal harmony is a delicate dance, and this latest purchase moved Jo Ann to steer her partner with a simple instruction: Why don’t you collect something smaller? In fact, she had a rather specific limit in mind: “Nothing bigger than a bread box.”

Potashnick was soon lamenting this new limitation to a friend in the antiques trade, who responded by showing him two items that would send him down a decades-deep rabbit hole. They were toothpicks. One had been carved out of ivory and decorated by a whaler in the mid-1800s. The other, “which was more ornate,” had been fashioned from bone.

“I said, ‘What are those?’” Potashnick recalls. “And she said, ‘You’re a dentist, aren’t you? You should look these up.’”

He bought the pair, set about searching for more information, and found that almost nothing had been written about the subject. “The last book of significance concentrating on the toothpick” was a 1913 monograph by a German dentist named Hans Sachs—which Potashnick eventually had translated and republished in English.

Yet toothpicks themselves constituted a realm of astonishing variety and artistry. The earliest known toothpick, excavated from Ur by C. Leonard Woolley during the joint archeological dig between Penn and the British Museum [“Oldest Examples of Writing Uncovered in Babylonia,” Jan 1924], dates to approximately 3500 BCE. Since then, humans have fashioned tooth-picking instruments from quills, bone, bronze, tortoiseshell, silver, gold, and celluloid; decorated them with sculpted birds, boots, pistols, monks and mermaids; encrusted them with rubies and diamonds; combined them with earspoons, tweezers, crochet hooks, pie crimpers, and mechanical pencils; and encased them in everything from mother-of-pearl to lion teeth.

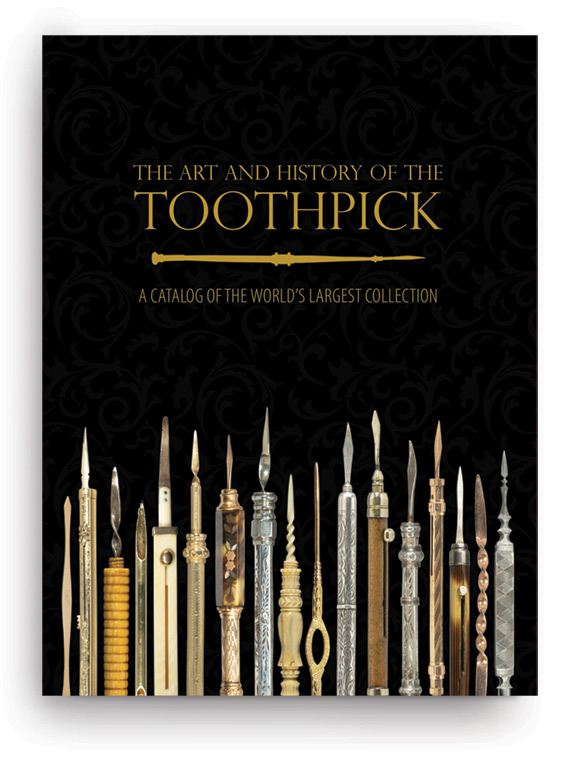

By Steven R. Potashnick GD’78

HenschelHAUS, 336 pages, $125

Beginning with that fateful encounter in the early 1990s, Potashnick amassed a collection of about 750 toothpicks, which then doubled in size with his 2007 acquisition of another collection built by Peter Katz, an England-based afficionado who’d caught Potashnick’s attention 10 years before by authoring a scholarly paper titled “The Toothpick and the Propelling Pencil.” The combined collections form the basis for Potashnick’s “COVID project,” a 336-page, sumptuously illustrated compendium called The Art and History of the Toothpick: A Catalog of the World’s Largest Collection.

The 2,800-image, full-color feast shows that the humble toothpick’s diminutive size seems to have only magnified the ingenuity applied to its manufacture. Here’s a miniature enameled silver sarcophagus concealing a retractable toothpick sprung loose by a “magic mechanism.” There’s a four-spoked bone contraption wrapped with tiny glass beads arranged by a Napoleonic prisoner of war into letters spelling out devotion to God. A section on Grooming Kits features a veritable Swiss Army Knife typology combining toothpick, earspoon, comb, and other implements within a decorative homage to the 1835 appearance of Halley’s Comet. A page devoted to “Victorian Risqué” features a celluloid toothpick in the form of a man whose hinged “genitalia can be fully hidden by the torso or rotated out to its unseemly position.”

Apart from the disposable wooden variety that began appearing in restaurants during the late 19th century (but do not figure in this collection), toothpicks have persistently been carved, lathed, cast, polished, and embellished like objets d’art. “The museum pieces from the Renaissance are gorgeous,” declares Potashnick, who draws several images from museums, including an early-16th-century portrait by the Italian painter Alessandro Oliverio depicting a wealthy patron wearing a fancy toothpick suspended from a gold neck chain. “I mean, they’re toothpicks, but I almost think that’s secondary to the artistic concepts that go along with them.”

Through the Industrial Revolution, toothpicks often served as “a way of showing your wealth”—be it by wielding precision-made mechanical pencil combo versions or carved-horn trinkets that served notice of a visit to the Eiffel Tower. The age of advertising also left its mark. Metal toothpick cases sang the praises of whiskey, beer, and cigars. Advances in printing turned celluloid toothpicks into miniature billboards. “PICK YOUR TEETH,” blared one exemplar. “Then pick your vocation by taking a course in CARLISLE COMMERICAL COLLEGE, CARLISLE, PA.”

Potashnick marvels over the endless forms toothpicks have taken. “If you can eat it, or if you can use it—like a bottle, a golf club, a carrot—then they probably also converted it into a toothpick.” Then there were ingenious creations like Sheldon’s Pocket Companion, an 1842 gadget that combined a toothpick, dip pen, pencil, and postage scale. “It’s just so clever!”

He hopes his book will serve as a resource for antique dealers—and a wake-up call for the many who have met his toothpick-related inquiries with blank stares. Toothpicks, he says, reflect shifting cultural circumstances, artistic tastes, and trends in manufacturing. “They started as objects in the natural environment”—grass stalks, for instance, used to dislodge irritating bits of dietary fiber—“and they evolved into something that was art, craft, novelty, and innovation.”

There’s just one thing the longtime member of the American Dental Association does not recommend: using them.

“They can be dangerous. People poke themselves with them. Toothpicks can sometimes increase the spaces between teeth,” Potashnick warns. “And the fact of the matter is that most of the toothpicks you see in the book were not used for hygiene purposes as we know it today. They weren’t thinking about biofilms and microbial plaque.”—TP