Chris Payne GAr’96’s photographs evoke the vanished world of state mental hospitals, where inmates could be both “mad and safe.”

By John Prendergast | Photography by Chris Payne GAr’96

“It’s a lot of fun to get into places most people can’t,” says architect and photographer Christopher Payne GAr’96. “There’s that sense of discovery when you’re wandering around the city. Most architects kind of look at things and wonder where they came from, how old they are, what’s the story behind it.”

For Payne, the attraction is all the greater when the structure in question has outlived its original purpose. In his first book, New York’s Forgotten Substations: The Power Behind the Subway, he explored the machines that once drove the city’s subway system and the structures that house them. Now he has published Asylum: Inside the Closed World of State Mental Hospitals (MIT Press), for which he visited more than 70 facilities in 30 states, most built in the last decades of the 19th century and the first few of the 20th.

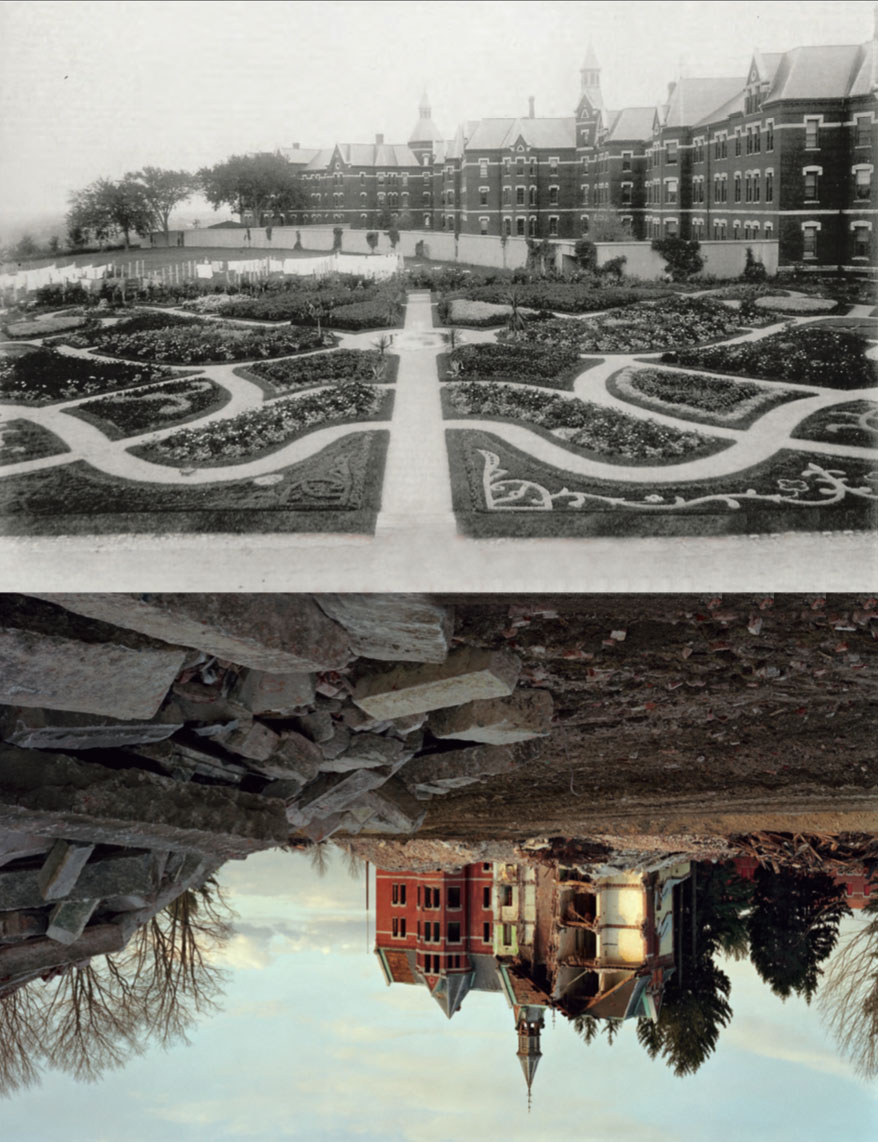

Once as much a source of civic pride as the local concert hall and museum, these institutions were designed to function as self-sufficient communities, with their own farms and dairies, laundries and kitchens in which the inmates worked. They featured imposing architecture, extensive landscaped grounds, and entertainments including bowling alleys, billiards and ping-pong tables, art studios and theaters. In an introductory essay, neurologist and author Oliver Sacks, who worked at a state hospital early in his career, writes that, at their best, these institutions were authentic places of refuge, where inmates could be both “mad and safe.”

Long plagued by overcrowding and underfunding, the state hospitals were ultimately done in by court decisions that effectively outlawed work by patients and a tidal wave of “deinstitutionalizations” as more effective drug treatments became available—a trend that brought its own set of problems. (Sacks quotes one former patient: “Bronx State is no picnic, but it is infinitely better than starving, freezing on the streets, or being knifed on the Bowery.”)

Operating at a fraction of their capacity or closed entirely, the hospitals have mostly fallen into disuse and decay. Sacks praises Payne’s photographs of these ruined structures, a sample of which are reproduced here, as “mute and heartbreaking testimony both to the pain of those with severe mental illness and to the once-heroic structures we built to try to assuage that pain.”

Patient toothbrushes, Hudson River State Hospital; ward hallway, Fergus Falls State Hospital.

Chris Payne traces his current career path back to a summer job for the National Park Service’s Historic American Building Survey and Historic American Engineering Record before and during his time as a graduate student in the School of Design. He was part of a team of students, historians, architects, and photographers sent around the country to document industrial structures and buildings.

As an architecture student, Payne drew plans and took measurements, but he soon came to suspect that the photographers had the better deal. “I would slave away on, let’s say, a grain elevator, or power plant, or cast-iron bridge somewhere, doing these drawings, and then a photographer would show up at the end of the project and take these amazing photographs,” he says. “I remember seeing the way these guys shot these structures and thinking, ‘Wow, that’s what I want to do.’ They were taking something that was very prosaic and kind of overlooked and turning it into art.”

At the same time, the comparatively freewheeling atmosphere of Penn’s architecture program—“I wouldn’t say it was all over the place, but it didn’t have a clear direction like most schools, [where] all the work looks the same,” he says approvingly—helped open him to the possibility that a traditional architecture career might not be the right one for him.

He became interested in architectural lighting and took a job in the field after graduation; still, “I knew it wasn’t quite the right fit.” What he calls his eureka moment arrived a year or so later: “I came across one of these old substations that the transit authority used to power the subway’s third rail, and I peered in and saw this working museum.”

Taking his old work with the Park Service a step further, he decided to create a book about the substations. “I would take measurements and do sketches of the machines,” he says. “I couldn’t finish them while I was there so I took photographs to finish the sketches. Gradually I became more interested in taking the pictures, and it began to remind me of the pictures the photographers would take on that summer job.”

Recognizing Payne’s growing interest, a friend who had offered to contribute photography to the project suggested he do it himself instead. “I started taking pictures and buying equipment, and I got a couple of grants and realized that was really where my passion lived,” he says.

Lobby and staircase, Yankton State Hospital; nurses station, Central State Hospital.

Both of Payne’s book projects have involved structures designed for a very specific purpose. “I’m very much interested in these [types of] purpose-built structures that have an architecture that goes with them,” he says. “Most of the things that are built now are mixed-use, retail, condominiums—everything is meant to be flexible. There is a sense of permanence to these older buildings that is very appealing.”

Shortly after the substation book came out, a friend suggested he consider shooting mental hospitals. Intrigued, he made a trip to Pilgrim State Hospital on Long Island, which, when constructed, was the largest institution of its kind. “Something like that, of that scale—it makes an impression on you,” he recalls. “I often wonder, if I had seen something much smaller, would I have continued?”

As he learned more about the state hospitals and their deterioration in recent decades, he felt an increasing urgency to document them. “You see something that has such beauty and uniqueness, and you realize that it’s not going to be there forever.”

He began approaching mental-health agencies in different states—“I’d say, ‘I’m doing this book and do you have anything old out there?’”—and one permission led to another as he crisscrossed the country. A number of the facilities he visited were still operational but at a vastly reduced capacity. At one hospital where 3,000 inmates had once been housed, there were 40 patients in residence. Unused space was either closed off or given over to other state agencies—often to serve as prisons. “You’ll have a huge campus and the buildings on one end have a big fence around them, and that’s a prison or some sort of correctional facility.”

In the Northeast especially, it was more common for the hospitals to be completely abandoned. “It was like driving into a ghost town, that sense of total dereliction and decay,” he says. “There wasn’t anyone around. Sometimes they wouldn’t even have security guards.”

“A lot of my early photographs were trying to get a grip on these complexes,” he adds. “In photography you’re dealing with a rectangular box, and how do you take those views? Sometimes I’d have to do a series of shots together. So a lot of the early stuff was just trying to comprehend and show the architecture.”

As time went by, he began to get a feel for the common features of the hospitals—the ward structure of long hallways with patients’ rooms opening off them, for instance. “For all the differences you are initially confronted with, over time you begin to see the similarities of all the hospitals,” he says. “By the end of the project I could move through a hospital and disregard things I knew weren’t essential or unique or that I had taken before.

“At the end I was really taking many more artifact type shots,” he says. “My last trip was mostly focused on taking pictures of straitjackets, medical equipment, things that didn’t interest me as much initially because they were too small.”

Unclaimed copper cremation urns, Oregon State Hospital; patient suitcases in ward attic, Bolivar State Hospital.

While there were “amazing shots everywhere I looked,” Payne says, his main goal was to find images that evoked the sense of the patients’ lives in these vanished worlds. “At the end of the day, I wanted each photograph to tell a story about the lives lived there. Each photograph should be able to stand on its own as an art shot but also be unique and reference all the other hospitals.”

He was a bit surprised at how accommodating officials were, allowing him access and even putting him up in dormitories. As it turned out, many staffers were eager to tell the stories of their institutions, seeing the book as an opportunity to counter the popular image of such hospitals as the brutal, overcrowded “snakepits” of popular culture.

“It’s not politically correct now, but the idea in fact of a place of refuge where people could go just to be crazy—at their best, they worked really well,” he says. “This is something I heard from a lot of people I talked to who worked there their whole lives. I didn’t hear all the bad stories.”

Even in their worst years of overcrowding and decline in the 1950s, patients could still be found “working in the shops, or bowling, or performing in a play,” he says. “You had good wards and bad wards, and buildings that were in good shape and vice versa.” Despite undoubted abuses, “at their core [these institutions] were set up with good intentions and certainly [state governments] would not have invested this much money in architectural infrastructure if they were just supposed to be warehouses.”

Payne admits that, for many of these structures, historic preservation is a hard sell. Their sheer size, deteriorated condition, and often remote locations all militate against their conversion to other uses. Not to mention the negative connotations associated with mental illness.

“It’s hard for the public to get past the fact that these were asylums and that horrible things happened in them,” he says. “That’s what we’ve been brought up to believe, and these gothic-looking castles reinforce that, when in fact there are other institutional buildings from the same period that look the same—they could be resort hotels, for instance, but they don’t have the same stigma.”

In an afterword, Payne focuses in on Danvers State Hospital in Danvers, Massachusetts, which was largely demolished for a condominium project on what had become prime real estate. A series of photographs in the book documents the destruction. “They saved the center core, but once you tear down the wings the building loses its sense of scale, and once you tear down all the trees that have grown up with the building, it lacks any sort of context and loses its historic integrity,” he says.

“I hesitated to tell the site manager how disturbing it was to watch this happen, since he represented the developer’s interests,” Payne writes. “But as we spoke, he echoed the same sense of loss I felt and added soberly: ‘When I first saw this place, I fell in love with it. Now without the building, it’s just a place, like any other.’”