In an era when publishing a poem or a political tirade takes little more than a mouse click, the basement of the Morgan Building is an incongruous place. The printed word is everywhere—draped over worktables and festooned on the white cinderblock walls—but it doesn’t flow from keyboards or toner cartridges. Indeed a quick glance at the posted list of commandments suggests that flow isn’t the right verb at all.

CLEAN ROLLERS, INK KNIVES, GLASS PALETTES WITH VEG. OIL FIRST, THEN SIMPLE GREEN OR MINERAL SPIRITS, reads one of the rules. LEAVE NOTHING IN BIG SINK IN ACID ROOM, says another.

Hanging from a nearby coat rack, next to a line of heavy aprons, an AOSafety brand gas mask promises protection against “organic vapors” and sulfur dioxide. Peek around the corner and the heart of the operation comes into view. Standing amidst cabinets filled with movable lead type are three letterpresses that weigh into the tons and have a combined age exceeding 250 years.

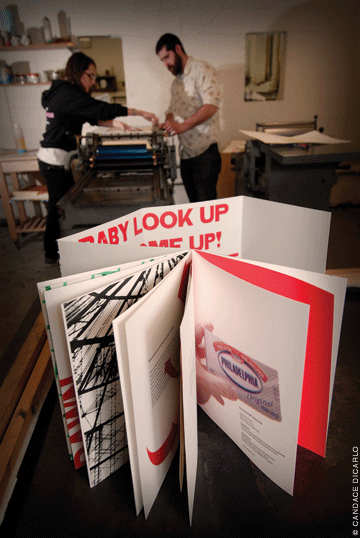

For the last two years Penn students and faculty have been using these bygone behemoths to create broadsheets and books the old-fashioned way: one letter at a time. Dubbed the Common Press, it’s a joint project of the School of Design, Kelly Writers House, and the Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

While the rest of the campus pulses to the wireless beat, the Common Press has become a refuge for people who want to put the wet ink and brow sweat back into publishing. “The handmade is back,” says Matt Neff GFA’05, a Penn Design lecturer and manager of the print shop.

He places his ink-stained hands on a 1960s-era machine that looks like it would smash an upright piano to dust and splinters. “It’s like finding an old Mustang or something,” he beams. “There’s about two guys in the country that fix them … Only one guy has the replacement parts, out in Colorado.”

A few moments later he turns his attention to a hand-powered model dating approximately to the Civil War. A wooden lever is yoked to a waffle of cast iron poised to smash its smooth underside against the type bed. It can be used to print not just pages, but scrolls.

“This is a true antique,” Neff says. “We got it from a museum.”

For the school, he allows, the machines were originally a tough sell. “To spend money on outdated technology isn’t too popular at a university that’s trying to get really new stuff.” But students are now learning things that newer technology can’t really teach.

David Comberg is a lecturer in the School of Design who played a key role in lobbying for University funds for the project. “The loss of the tactile and manual in art and design training—even in writing, the sort of digitalization of everything—I think there’s a price that students have paid for that,” he says. “There are a lot of advantages to working abstractly. But the thing that has been gained by this is recognition that your hand and materiality are a key part of what you make.

“We certainly use digital tools in concert with manual tools,” he continues, “but the manual tool really helps the students, particularly in teaching typography, recognize that letters are things. They’re not ideas or abstractions. They’re actual materials that are composed together to make writing.”

Erin Gautsche GGS’06, program coordinator for the Kelly Writers House, has noticed that students write differently when they have to construct words by hand. “When you’re actually laying one letter at a time,” she says, “it really changes how students, audience members, and participants think about the work … Every space is a conscious choice. A line break becomes something much more physical, because it’s something you make. We find that people connect with poems in a really different way. And it makes them think about writing in a different way, too.”

When the shop was just getting off the ground, for example, the most mundane limitations often served as artistic spurs. “Sometimes there weren’t enough e’s,” Gautsche recalls. “And so you’d have to change things, to work with what you have … It can create some really interesting writing.”

Now, Gautsche and Neff are preparing for a course in design and creative writing they will co-teach next fall. The presses will play a central role; each student will use them to create a book by semester’s end.

“We’re going to do a little bit of the history of the artist book,” says Gautsche.

“And then we’re going to look at the grotesque in visual history,” Neff adds. Starting out with gruesome monsters depicted in age-old books with dusty covers, the class will hurtle ahead to explore and perhaps shape the future of this nearly vanished medium. “There’s a lot to pull from in contemporary art and culture,” Neff points out. “I’m just excited to see what happens.”

Smiling broadly and casting his eyes around the room, he adds the obvious.

“This is a weird part of Penn, this basement.”

—T.P.