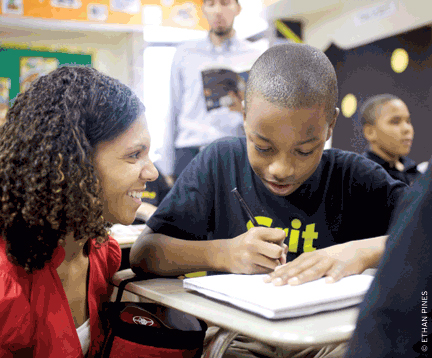

Penn psychologist Angela Duckworth Gr’06 argues that character—not intelligence, quality of instruction, family situation, or income level—is the crucial determinant of achievement in school. Now she just has to figure out how to measure character—and influence it for the better.

By Kevin Hartnett | Photography by Chris Crisman C’03

Every year large percentages of American elementary-school students fail to learn basic math skills like how to add fractions with unlike denominators. The situation is even worse among students from the poorest American neighborhoods, despite the fact that from fourth grade on their teachers drill them in these simple steps: find a common denominator; add the numerators; reduce.

There are many explanations for why such a simple procedure proves to be so hard to convey. Reformers and policymakers point to subpar teachers and inadequate principals; to single-parenthood and other demographic drags; to health, nutrition, and the intangible handicaps of poverty.

Assistant Professor of Psychology Angela Duckworth Gr’06 has another explanation. Before she entered graduate school at Penn in 2002 she spent five years teaching math and science in poor urban neighborhoods across the United States. In that time she concluded that the failure of students to acquire basic skills was not attributable to the difficulty of the material, or to a lack of intelligence, or indeed to any of the factors mentioned above. Her intuition told her that the real problem was character.

“Underachievement among American youth is often blamed on inadequate teachers, boring textbooks, and large class sizes,” she wrote in a paper titled “Self-Discipline Outdoes IQ in Predicting Academic Performance in Adolescents,” which served as her first-year graduate thesis and was published in Psychological Science in 2005. “We suggest another reason for students falling short of their intellectual potential: their failure to exercise self-discipline … We believe that many of America’s children have trouble making choices that require them to sacrifice short-term pleasure for long-term gain, and that programs that build self-discipline may be the royal road to building academic achievement.”

Effortful practice; persistence though boredom and frustration; gritty determination in pursuit of a long-term goal. In Duckworth’s view these are the qualities that separate more and less successful students, and in recent years she’s emerged as one of the most influential voices in American education reform, where she argues that cultivating “achievement character” in kids may be the last, best way to narrow educational inequality in America.

“Schoolwork is not hard in the way that electromagnetism is hard. It is hard because it’s aversive and not fun to do,” Duckworth, who joined the faculty at Penn in 2007, explains. “So the straightforwardness of the material combined with the abject failure of students to learn it made me think there must be something besides IQ holding them back. That’s maybe more obvious for teachers than it is for policymakers.”

The intuitive appeal and expansive application of Duckworth’s research has earned her increasing popular recognition (a New Yorker profile is in the works) as well as a privileged position at the crossroads of basic research and public policy. This past fall U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan invited Duckworth down to Washington to share her policy recommendations. There she cautioned Duncan about the usefulness of standardized tests as an accountability tool, arguing that performance on those tests tends to be more a function of native intelligence (IQ) than of how well students are actually learning in their classrooms. She also urged Duncan to throw the full weight of the Department of Education behind initiatives to use “the hard-fought insights of psychological science” to improve the way schools teach students.

Duckworth’s experience as a classroom teacher has also helped her build strong ties in the education reform community, where leaders like Dave Levin, the co-founder of the KIPP (Knowledge is Power Program) charter-school network, consider her a kindred spirit and are using her work to develop strategies for teaching achievement character to low-income kids. Duckworth is best known for the study of “grit,” which she defines as “perseverance and passion for long-term goals.” Today grit is a buzzword in the hallways of charter schools around the country, where teachers, principals, and deep-pocketed board members have all come to believe that inculcating grittiness in students is every bit as important as building academic skills.

Duckworth’s view, if correct, would have dramatic implications for the way policymakers and educators think about student achievement. It also raises provocative questions about the limits of research in the social sciences and the malleability of human character: Is it possible to design measurements to quantify character with the same precision that researchers quantify intelligence? And if so, are self-control and persistence amenable to cultivation, let alone on the scale of public policy?

Angela Lee Duckworth grew up in Cherry Hill, New Jersey, the daughter of well-educated parents who’d immigrated from China. She’s quick to say her mom and dad were not Tiger Parents, though academic success was always assumed. What was less expected of her, she says, was that she’d throw herself into community service. “When I was in high school I was sort of spontaneously and not very reflectively drawn to public service activities,” she says. “I don’t know where that impulse came from. You could do some retrospective reconstruction, but that is always a dangerous game to play.”

When Duckworth was 18 she went to Harvard, where she majored in neurobiology but continued to perplex her father (who is a color chemist at DuPont) by devoting much of her time to leadership roles in several community service organizations. “I don’t think in Chinese culture there is as much of a tradition of helping anonymous strangers of a different race,” she says. “My dad was like, ‘ You have a science degree from Harvard but instead you want to spend your time helping poor black kids?’”

Following graduation Duckworth spent two years founding a summer program for disadvantaged kids and then went to Oxford on a Marshall Scholarship. After returning from Oxford she consulted with McKinsey for a year and spent another year as the chief operating officer of a web startup called Great Schools that allows parents to compare public schools. But the bulk of her time over the next seven years was spent teaching math and science at public schools in New York, San Francisco, and Philadelphia.

“It seemed to me that if I was going to work on issues of equity I should start earlier in the life course rather than later,” she says, explaining why she was drawn to the classroom. “The earlier you start the bigger bang for your buck you get in terms of closing the gap between the privileged and the non-privileged. I also just enjoyed working with young people, so that kind of led naturally to teaching.”

Duckworth jokes that the job-hopping she did in her twenties was a case study in “how not to be gritty,” but it seems more a function of the intensity and dynamism of her personality. In the course of reporting this article I heard colleagues call Duckworth the most extroverted person, the quickest learner, and the fastest thinker (and talker) they’d ever met.

On the day I visited she had a half-dozen bubble gum containers on her desk, suggesting an atmosphere of restless activity and a need to replenish the saliva that’s lost through such rapid-fire speech. She also uses expletives in a way that might impress even high-powered cursers like Rahm Emanuel. In the course of a 90-minute conversation she called a principal she knew “an asshole,” described the opinion of a leading education foundation as “fucking idiotic,” and did a spot-on impression of a teenager with attitude when explaining the challenge of conducting experiments with adolescents: “When you pay adults they always work harder but sometimes in schools when I’ve done experiments with monetary incentives there’s this like adolescent ‘fuck you’ response. They’ll be like ‘Oh, you really want me to do well on this test? Fuck you, I’m going to do exactly the opposite.’”

Duckworth also has a degree of entrepreneurial energy that, at first blush, makes her an odd fit for the academy. I asked her whether she sees herself more as a reformer, like Dave Levin, the KIPP founder—driven by the desire to achieve specific outcomes—or as a scientist—dedicated to asking questions and following prescribed methods for answering them.

“I think that Dave and I have always had this passionate commitment to children combined with an incredible amount of energy and optimism about doing,” Duckworth says. “My dad used to say to me, ‘There are thinkers and there are doers.’ Very few people are both. And I think to the extent that I’m a professor I’m a thinker and it’s my duty to analyze things and see if I can figure out how the world works. But Dave and I are both very much doers. We share a kind of boldness, an attitude of just try it, just do it, and don’t just sit on your hands and think all day.”

For most of her time as a teacher she assumed she’d apply her insights about student achievement by opening her own charter school, which would have allowed her to stay in public education while also giving her significant discretion over exactly how and what students were taught. But after five years in the classroom, ending in a stint teaching high school science at Mastery Charter in West Philadelphia, she concluded that charter schools were not the answer to the achievement gap.

“I looked around at these charter schools and it seemed to me intuitively they weren’t the way to reform education,” she says. “I saw these charter schools writing their own curricula, creating their own HR departments, and it seemed to me intuitively that the diseconomies of scale were working against them.” (Today she says her critique was wrong, owing to “a lack of imagination” when it came to foreseeing the development of national charter organizations like KIPP and Mastery, which provide their network schools with the efficiencies of scale that early charters lacked.)

Duckworth wasn’t going to open her own school, but she still wanted to make a bigger impact on public education than she could as a teacher—at first, she just didn’t know how. “I thought about the biggest problem that needs to be solved in K-12 education and then I listed out all the things I’m good at: I like to write, I like analysis, I like math, I like to think hard about problems,” she says. “So I sort of put the Venn diagrams together and in a very top-down deductive way I concluded I should go into psychology and become a researcher in order to understand these character competencies, and then go back into these schools and help them solve their achievement problems.”

One night in July 2002 Duckworth was up late with her infant daughter (she and her husband, the president of a Philadelphia-area real-estate investment fund, now have two girls), and researching psychology programs online when she came across the website of Martin Seligman Gr’67, the Zellerbach Family Professor of Psychology and director of Penn’s Positive Psychology Center (not to mention the founder of the discipline). Duckworth, who’d never taken a psychology class before, was such a neophyte in the field that she didn’t recognize Seligman’s name. “I didn’t know he was famous. I was like, he writes very well, I like his website, so I emailed him,” she says.

As it happened, Seligman was up late too, playing bridge online [“Passion Play,” Mar|Apr 2011]. He replied to Duckworth’s email within minutes, inviting her to attend a research meeting at his house the next day—and ended up being so bowled over by Duckworth’s super-charged demeanor that he would ultimately convince his colleagues to throw the admissions timeline out the window and allow Duckworth to join the program that September. All things considered, it wasn’t a hard sell. “Angela was fast, about as fast mentally as it is possible for a human being to be,” Seligman writes in his latest book, Flourish: A Visionary Understanding of Happiness and Well-being. “She blew us away in the interview. In violation of precedent, the admissions committee gave in and accepted her.”

For her part, Duckworth was drawn to the Positive Psychology Center because of the way it encourages students to think about the real-world implications of their research. “Marty is only interested in questions with significant relevance to people’s well being,” Duckworth says. “Marty is a basic scientist, of course, but he’s always been someone with one foot in the world beyond the lab. He’s always cared about how psychology actually changes people’s lives within his lifetime for the better. I came in to graduate school very much in that view, and it only got reinforced while I was there.”

Achievement—the main focus of Duckworth’s research—is the last of the five key elements in positive psychology’s taxonomy of well-being, which goes by the acronym PERMA. (The others are Positive Emotion, Engagement, Relationships, and Meaning.) For decades psychologists studying achievement focused almost exclusively on intelligence. As Duckworth saw it the problem with this single-minded emphasis was two-fold. For one, IQ scores didn’t explain everything about why some individuals achieve more than others. In fact, they were not even particularly good at predicting something as basic as the amount of education adolescent-aged kids would go on to attain later in life.

The second problem was more practical: IQ may be easy to measure, but it’s hard to change. IQ tests given as early as kindergarten are highly predictive of adult intelligence, meaning that if boosting intelligence was the only way to boost academic achievement, reformers were not going to get far.

The story was very different with personality. While IQ stabilizes before kids even learn to read, many psychologists including Duckworth point to longitudinal survey data to conclude that personality doesn’t become similarly fixed until at least age 50. Along the way average levels of personality traits change (most people become more conscientious as they grow older), as do rank-order levels, meaning that the most conscientious 10-year-olds are not necessarily the most conscientious adults four decades later. To Duckworth, this fluidity suggested a tantalizing possibility: If personality evolves so much as people get older, why shouldn’t schools be able to influence the direction in which it changes?

Before Duckworth can hope to modify personality she needs to know how to measure it, which is no small task. In fact, according to Seligman, measurement challenges are the primary reason that researchers have long shied away from studying personality.

“There’s a hegemony of silence in science, things you don’t work on because they are too fuzzy,” Seligman says. “So, while the importance of self-control, self-discipline, grit may be obvious once we’ve said it, that doesn’t mean that they become eligible as scientific endeavors until a creative person like Angela comes along and says, ‘Oh come on, we can measure these things!’”

Duckworth is naturally optimistic about the potential for human ingenuity to solve social problems. She likes to say, “Rather than curse the darkness, light a candle,” but in her very first research project as a graduate student at the PPC the darkness won. Her years in the classroom had convinced her that persistence was essential for academic achievement, so she designed a study in which students were asked to find a pattern in what was (unknown to them) a series of non-repeating digits. The problem, though, was that no one gave up within the allotted time. “I found, as has been found by many psychologists, that any good lab experiment has to end within 60 minutes,” Duckworth says. “But I couldn’t find a task that was so frustrating that people would give up within that time.”

After failing to measure persistence Duckworth shifted to self-control, which researchers had been studying since 1972 when the eminent psychologist Walter Mischel conducted his famous “marshmallow test.” Mischel presented pre-kindergarteners with a marshmallow but told them they could have two if they waited 15 minutes to eat the first. In a conclusion that hovers over middle-class parenting across America, Mischel found that kids who were able to hold out for the second marshmallow tended to have higher SAT scores years later.

Duckworth conducted her own version of Mischel’s experiment with students at the Julia R. Masterman Laboratory and Demonstration School, Philadelphia’s top magnet school, and drew on additional measurement techniques to make her results more robust. In the fall of 2002 she offered 140 eighth graders a choice between receiving $1 immediately or $2 a week later, and also administered self-control questionnaires to the students, their parents, and their teachers. She combined her survey and experimental data to create a “self-control index,” which she used to anticipate how well students would fare on their final report cards. When grades came out that spring she found that self-control and GPA were not only strongly correlated—her self-control index was twice as good at predicting academic performance as IQ scores.

Following the Masterman study, Duckworth turned to what has become her signature topic—grit. Grit is a nebulous concept compared to self-control, and the way people pursue long-term goals is hard to measure experimentally. So instead of a lab task Duckworth developed the “Grit Scale,” a 12-item questionnaire that asks respondents to rate themselves on statements like “Setbacks don’t discourage me” and “I have difficulty maintaining my focus on projects that take more than a few months to complete.”

Duckworth wanted to test the Grit Scale in high-achieving populations, to see if it could reveal distinctions even within groups where everyone was talented. In 2004 she administered the Grit Scale to 1,200 incoming cadets at West Point, just before they began “Beast Barracks,” the academy’s intensive summer training program that every year leads 5 percent of admitted freshmen to drop out.

Admission to West Point is determined in large part by a “Whole Candidate Score,” a weighted index comprised of variables like SAT score, class rank, and performance on the Army’s Physical Aptitude Exam. Duckworth found, however, that cadets with the highest scores on the Grit Scale were 60 percent more likely to make it through Beast Barracks than cadets of merely average grittiness. What’s more, her Grit Scale was nearly four times as good at predicting which cadets would drop out as any of the Whole Candidate Score indicators that the Army had spent years refining.

Despite this and other successes administering the Grit Scale (she’s used it to study Scripps National Spelling Bee Contestants and Ivy League college students, among others), Duckworth acknowledges that questionnaires have significant pitfalls as a research tool: answers can be faked and respondents are often biased when evaluating people they know. Even more significant, people don’t have a good intuitive sense of the appropriate scale to use when assessing their own personalities.

“Let’s say I ask you to evaluate yourself on the question, ‘I am a hard worker.’ What standard would you use?” Duckworth says. She ran into this problem recently while studying delay of gratification in students in the US and Taiwan. On objective measures US students showed much less self-control, but on surveys they gave themselves higher marks than Taiwanese students gave themselves.

The success of Duckworth’s research will hinge ultimately on whether she and her colleagues can devise measurement tools that produce more replicable and precise results than the ones they are using today. Or, as she puts it, “If we cannot figure out how to measure these characteristics in some kind of reasonable timeframe, with some kind of objectivity, the research will grind to a halt because we can’t measure what it is that we want to actually study.”

Measurement innovations are at the heart of two large-scale projects that Duckworth is launching this year: The first is a three-year-long study of self-control funded by a grant from the John Templeton Foundation. Students ranging from pre-kindergarteners to college seniors will be asked to complete boring software tasks while resisting the temptation to divert their attention to more entertaining pursuits.

On the day I visited Duckworth she was holding a conference call where the project team was debating whether to have kids use iPads or computers in the experiment. (The concern was that very young kids wouldn’t be dexterous enough with a mouse; in the end the team decided on iPads and within a couple weeks Duckworth had rounded up an additional $10,000 of funding to pay for them).

“So kids are going to be doing these boring tasks on iPads while trying to resist the temptation of switching over to play Angry Birds,” Duckworth says, referring to the notoriously addictive online game. “We’ll measure how well kids exert self-control in the face of temptation to take immediate gratification. Once we have these measurements established the question will be identifying strategies kids can adopt that will make it easier for them to do well in these tasks.”

The second study is on college persistence and will be carried out over the next two years with a $1.8 million grant from the Gates Foundation. College persistence has become a hot topic recently, as evidence has emerged showing that even when low-income students catch up academically with their middle-class peers, they still end up dropping out of college at disproportionately high rates. Most recently, the KIPP Foundation reported that while its intensive approach to academic instruction succeeded in getting 80 percent of its students into college over the last decade, only 33 percent of those students ended up with a college diploma. That number is above the 8 percent of low-income students nationwide who complete college, but it still falls well short of college graduation rates for middle-class students.

In the Gates project, Duckworth and a group of high-profile collaborators will conduct several studies that attempt to quantify the personality factors that distinguish college graduates from college dropouts with similar demographic and academic backgrounds. Their goal will be to “provide new insight into student factors that predict college persistence and develop strategies to cultivate them via school-based interventions.”

Duckworth’s part of the study is based on the work of Anders Ericsson, the Florida State University psychologist whose work on the personality characteristics and training habits of truly exceptional performers was popularized in Malcolm Gladwell’s recent best-seller Outliers. Duckworth and her research team will conduct an in-depth analysis of a small number of high school students from minority backgrounds who demonstrated superior academic growth from ninth to 12th grade. These superstar students will be compared against peers who entered high school at similar levels of achievement but made significantly less academic progress en route to graduation. One technique she’ll be using to make the comparisons is an innovative new measure called an “emote-aloud protocol” in which participants are instructed to narrate their feelings as they perform a demanding task.

“We’re going to be applying the same methodology that Ericsson used to understand Olympic athletes to understand kids in school,” Duckworth says. “We’re going to put the kids under the microscope to understand what high-achieving kids do differently. We’ll follow them through college and see whether the habits we identify actually have a payoff when they’re in a new environment. We want to know what achievement personality looks like in kids and how we get more of it—what do you do, what do the parents do, what do the schools do.”

The most concerted effort to date to implement Duckworth’s research is taking place at KIPP Infinity Middle School in Harlem, New York. The KIPP network of charter schools was co-founded by Dave Levin and Mike Feinberg C’91 [“Alumni Profiles,” Nov|Dec 2000] in Houston in 1994, when they were both working as fifth-grade teachers through Teach for America. Since then KIPP has expanded to 109 schools in 30 low-income regions around the country, and has become one of the most prominent education-reform organizations in the country.

The KIPP model is based on the premise that a high-performing school by itself can overcome the disadvantage that poor, typically minority students face in many other areas of their lives. The basic tools of a KIPP school are an extended school day (often running from 7:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. or later), a longer school year, intensive math and literacy instruction, and a pervasive focus on the goal of graduating from college.

From the beginning, character development has been an essential part of a KIPP education, as captured by the organization’s ubiquitous slogan: “Work Hard. Be Nice.” Over the last five years Levin, who serves on the KIPP board of directors and is superintendent of KIPP’s eight schools in the New York area, has teamed up with Duckworth to formalize the way KIPP NYC teaches character—to measure and monitor it, and institute strategies for enhancing it.

The cornerstone of the initiative is the “KIPP Character Report Card,” which teachers use to assess students on character traits that KIPP considers intrinsic to high achievement. The idea for the character report cards originated in a 2005 meeting at Penn that included Seligman, Levin, Duckworth, and Christopher Peterson, a psychologist at the University of Michigan.

At the time of the meeting Peterson and Seligman had just finished collaboration on an 800-page tome called Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification. To write the book they had scoured essential texts from cultures throughout history, looking for character strengths that have been considered building blocks of the good life no matter where or who you are. In the end they came up with 24, ranging from bravery to prudence to self-control.

Peterson and Seligman’s book provided Levin with a framework for thinking about character in a more systematic way, and in Duckworth he found the perfect person to help him translate that framework into an assessment tool he could use at KIPP. “Angela is one of the elite people in the country to combine a deep understanding of K-12 education with the highest credentials of a researcher,” Levin says. “It was a natural fit for us to work together.”

Levin and Duckworth’s first step was to boil the 24 traits down to those with particular relevance for school. They removed traits like modesty, spirituality, and fairness, and settled on a list of seven that seemed particularly essential for high academic achievement: zest, grit, self-control, curiosity, social intelligence, gratitude, and optimism. (Love actually made the initial cut, but, Duckworth says, “Dave didn’t want to have to tell a parent, ‘Your kid is low on love,’” so they swapped it out for curiosity.)

Once the seven traits had been determined, the next step was to figure out how to measure them—to define, for example, what optimism or zest looks like in practice. The criteria for measuring each trait didn’t have to produce results that concurred with some absolute value, because there is no truly objective definition or measure of something like zest. Instead, Levin and Duckworth’s goal was to agree on criteria that matched their general understanding of the character traits, that were easy for teachers to observe, and that produced results which corresponded roughly with anecdotal evaluations of which students had more or less of a given trait.

In the final KIPP Character Report Card each trait is broken down into two to four indicators on which students are given scores from 1-5. The indicators for optimism are “Gets over frustrations and setbacks quickly” and “Believes that effort will improve his or her future.” One of the indicators for zest is the relatively easy to quantify “Actively participates,” while another is the less tangible “Invigorates others.” Indicators for self-control are more concrete and include: “Comes to class prepared,” “Allows others to speak without interruption,” and “Remembers and follows directions.”

Duckworth is aware that measuring character to two decimal places on a report card could be perceived as unduly harsh, particularly if it’s seen to overlook the role that poverty plays in depressing achievement among low-income students. But in her view character isn’t purely innate—instead, she argues, it’s just as influenced by environmental forces as things like reading scores and high school graduation rates, which most people feel entirely comfortable quantifying and evaluating.

“One of the problems with the word character is that it carries a lot of baggage,” Duckworth says. “People sometimes think that emphasizing character means not emphasizing environmental conditions like growing up in poverty or not having good role models. But I think it’s a false distinction, because your character is influenced by how you grew up—it’s not like there’s character on one side and environmental forces on the other. Given that, if you wanted to help kids, it’s not immediately obvious how you’d go about changing poverty. So the direction I’m more excited about is the effects that schools can have on kids. We might not be able to make a family richer, but maybe we can make their kids grittier or more self-controlled.”

There is scattered evidence showing that programmatic school-based character interventions work. Some of the most frequently cited interventions include Tools of the Mind, a preschool program that helps students develop self-regulation tools, and the Chicago School Readiness Project, which trains preschool teachers on how to instruct kids in self-control. Overall, though, the research in this area has been limited. It’s still unknown whether personality is like a person’s height—which is measurable, but not modifiable—or whether it’s more like blood pressure or cholesterol levels, which can be measured and modified, and which can be influenced at a population level by public health initiatives.

At the end of my conversation with Seligman I asked him whether he thinks we’ll see the day when schools are teaching kids grit and self-control alongside phonics and fractions. I expected the father of positive psychology to be bullish, but he was surprisingly skeptical. “I think Angela has made some progress in this area,” he said. “But it is interesting to me that for 3,000 years at least teachers have been trying to get more self-discipline out of kids without figuring out how. So for me the modification of grit and self-discipline are still hopes and promissory notes as opposed to fact.”

For Duckworth, however, the challenge of her research question is part of its appeal. She spent the first decade of her professional life unsure of how to apply her abundant talent. Now she no longer has any doubts. “I have complete conviction that this is an incredibly important scientific question,” she says. “If we can figure out the science of behavior and behavior change, if we can figure out what is motivation and how to motivate people, what is frustration and howdo we manage it, what is temptation and why do people succumb to it—that to me would be akin to the semiconductor.”

Kevin Hartnett, a former teacher, is a freelance writer living in Ann Arbor, Michigan. A collection of his work can be found at GrowingSideways.net.