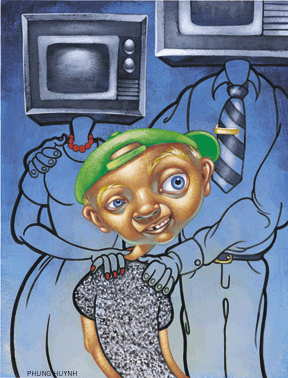

Kids spend more than 20 hours a week in front of the TV. Are yours watching what they should? Would you know? Researchers at the Annenberg Public Policy Center have some answers.

By Leslie Whitaker | Illustrations by Phung Huynh

Sidebar: What’s It Rated?

Sprawled out on the couch, a 12-year-old lazily watches TV until his mother approaches the room, prompting him to tense up. His hand grazes the remote control before he greets her with a forced smile. Was he sneaking a peak at Real World, MTV’s show about twentysomethings that she forbade him to watch months ago? she wonders. Or was he actually tuned in to that charming Nickelodeon cartoon Little Bear all along, as he maintains?

Well mom doesn’t have to wonder any more. Thanks to the V-Chip, new technology that is being built into all new television sets with screens 13 inches or larger, parents can block shows with the press of a few buttons on a remote transmitter. The V-Chip picks up ratings transmitted by broadcasters that indicate the target age for a program or the presence of potentially objectionable content, such as violence, sexual situations and crude language. (For a quick tutorial, see box on page 38.)

While optimists may hope that this in-home censor signals the dawn of a new age in which children are fed a restricted television diet that includes only enriching and wholesome shows, the coterie of researchers at the Annenberg Public Policy Center (APPC) who study the relationship between children and television know the picture is far more fuzzy. Not even the latest gadget can possibly screen out all the undesirable influences, cautions Dr. Amy Jordan ASC’86 Gr’90, senior research investigator at the center. With constantly changing lineups and evolving government regulations, children’s programming has become “very cluttered and confusing.”

Undeterred by the increasing popularity of computers and video games, television continues to play a major role in the lives of children. (It turns out that new media isn’t replacing TV so much as supplementing it.) They spend just as much time watching TV as they do sitting in a classroom—a staggering 1,000 hours a year. No wonder today’s adolescents have an easier time recognizing the Simpsons and the characters in Budweiser commercials than naming the vice president of the United States, one of the APPC’s findings. With the increasing numbers of children who have television sets in their own room—48 percent at this writing—this influence shows no sign of waning.

For their part, most parents watch as little children’s TV as possible because its loud noises, bright colors and constant motion are not geared to their sensibilities. “It’s a painful thing to do,” admits Jordan. So when parents snuggle up with their kids on the couch to watch TV, they typically tune in to shows that, while they may be suitable for children, are made for a general audience. Only 25 percent of the shows most-watched by children between two and 17 years old were specifically designed for them; the top four were Sabrina the Teenage Witch, Boy Meets World, Two of a Kind and Brother’s Keeper—aired between 8 p.m. and 10 p.m. Fridays on ABC’s “TGIF” programming block. Even many network executives in children’s TV avoid all but their own shows.

That’s why the work that Jordan is leading at APPC is so important: this research tries to get a handle on the big, constantly changing picture of what’s available for children. “We’re the ones who track the quantity and quality,” she explains. “We’re always trying to figure out how new regulations and the media environment have changed.”

Initially, Jordan imagined a career for herself in front of the TV cameras. As an undergraduate at Muhlenberg College, she studied communications and “wanted to be the next Barbara Walters.” An internship at an Allentown, Pa., TV station provided a reality check. She found the “rip and read” approach to being a newscaster “quite boring,” she says, and also began to have larger questions about the media—especially its impact on children.

Her senior thesis at Muhlenberg was on a notoriously sweet, then-popular cartoon show, The Smurfs. “I became very intrigued by the stereotypes presented” by the program, she recalls, “and offended by the fact that they had only one female character: Smurfette.” Her thesis advisor had studied with former Annenberg School Dean George Gerbner as a doctoral student, which helped lead Jordan to the school for her master’s and Ph.D. degrees.

“At the time I was going through the program, there were few opportunities to work on research outside of that which was required for class,” she says. “Things are very different now that I’m back. Students have lots of opportunities to work on grant projects and roll up their sleeves and see research from conception to completion.” She was “lucky,” she says, to get the chance to work with Dr. Christine Bachen (now at the University of Santa Clara) on a project studying children’s political socialization, which “got me into the field and gave me the extraordinarily valuable skill of being able to effectively interview kids.”

Jordan was an assistant professor and coordinator of the media-studies program at Widener University and then, wanting to do more research, took a

position as research associate at the non-profit organization Public/Private Ventures, which designs and evaluates social programs for disadvantaged youth. In 1995, while on maternity leave after the birth of her third child, Jordan was teaching an undergraduate communications course at Annenberg—just when Dr. Kathleen Hall Jamieson, professor of communication and dean of the Annenberg School, who also directs the APPC, had decided to develop a research focus in children’s TV. “[At the time], it was becoming a hot policy area with the Three-Hour Rule and the V-Chip legislation,” Jordan recalls. “She needed someone to head up the research. I applied for the job and luckily got it.”

With a stuffed Po (the red Teletubby) and Scooby Doo looking on from her office windowsill, Jordan and her team of Annenberg students and research fellows view show after show. As they watch, the researchers track the good and the bad, variables such as the quality of the educational content (if there is any), the ethnic and gender diversity of the characters, and the number of violent incidents, problematic language and sexual innuendo.

For the past four years, this research has culminated in the release of a widely-publicized annual report on the “State of Children’s Television.” (Visit the center’s Web site www.appcpenn.org for the complete text and related research.) Last summer’s report contained some moderately good news. The number of children’s shows increased by 12 percent, which meant there was more to choose from. And the percentage of shows judged to have no “enriching content”—shows like UPN’s violence-laden Beast Wars —had decreased by almost half, to 25 percent. Annenberg’s standard for enriching content is based on a quality index that measures the extent to which programs include potentially enriching content and exclude potentially harmful content, such as violence, which has been tied to aggression in young viewers. “Children’s programming is improving,” concludes Dr. Emory Woodard IV ASC’95 Gr’98, a research fellow and author of last year’s report. “Is it the watershed development we’d love to see? No. Hopefully it will keep improving.”

On the downside, the Annenberg researchers found that more than a quarter of children’s shows contain four or more incidents of violence, considered “a lot” in their analysis. They consider any overt depiction of intentional or physical force as a violent incident. Furthermore, because the rating system used by broadcasters is voluntary, not all of the networks coded these shows with the FV (fantasy violence) rating, which would alert parents. The researchers also found that 45 percent of children’s programs contain one or more instances of problematic language and 12 percent contain one or more instances of sexual innuendo.

While Jordan’s three children, ages 11, six and five, may not appreciate her work—“They can’t get anything by me, because I know everything that’s on,” she says—government regulators, children’s advocates and even broadcasters, do. “It’s clear that the orientation is toward advocacy for children, but they don’t take extreme positions,” says Dr. Karen Hill-Scott, a Los Angeles-based media consultant. “There is an attempt to honestly evaluate what they’re viewing, and people on both sides of the table respect that.”

Donna Mitroff, senior vice president, educational policies and program practices for Fox Family Worldwide, agrees. “I’m a big supporter of what they do,” she says. “Sometimes it feels like a pain in the neck. But they do a terrific job of publicizing their study and what they do calls attention to high-quality shows. If the public is made aware of good shows and looks for them, the networks will create them.”

A few years ago Jordan tried to make one promising show even better. Intrigued by Fox’s show Bobby’s World, which tried to encourage reading by including captioning at the bottom of the screen so children could follow along with the dialogue, she watched the show. But she spotted a problem: the captioning did not match the dialogue. One reason was that Howie Mandell, the comedian who supplied some of the voices, was prone to ad libbing. “I called up the VP at Fox and told him it wasn’t verbatim,” says Jordan. “He didn’t know that, which is not surprising because no one looks carefully at children’s programs.” Once alerted, the network proceeded to investigate what was the best way to encourage reading, through verbatim captioning or paraphrase. The answer turned out to be verbatim. “That’s one place where I think we made a difference,” she says. “It’s not always such a friendly conversation [with broadcasters]. But we do have a dialogue going.”

Parents rarely are as proactive. Studies by both Annenberg and the Kaiser Family Foundation have found that while more than 70 percent of parents said they would use a V-Chip to block shows they didn’t want their children to watch, just as high a percentage indicated that they would not purchase a set or a box-top unit that plugs into an older set (retail price: $100 or less) specifically to acquire the V-Chip technology. Furthermore, while a majority of parents have heard about the broadcasters’ rating system, few have bothered to learn much about it. “When you ask hard questions, like, ‘What does a V stand for?’ very few know,” contends Woodard.

That’s why the V-Chip is the latest item on the Annenberg group’s research agenda. “We’ve never been advocates of censorship,” Woodard insists. “But we do think it’s another means of empowering parents, an alternative tool. As families naturally purchase new sets and get the technology, they will likely use it. But we’re pushing the envelope to see what conditions may affect its use.”

Funded by a $300,000 grant from a private family foundation (which prefers to remain anonymous), the researchers have embarked on a yearlong study of 180 Philadelphia families to study the impact of the V-Chip. Jordan and company handed out free new sets to 120 families who agreed to participate in the study. Half of them (dubbed the high-information group) will receive information and training about how to use the device and why it’s important. The other half (the low-information group) will receive nothing more than the set and the printed material that normally accompanies a new set. “This group must resemble natural conditions,” Woodard explains.

The third group of 60 families, which did not receive new sets, will serve as the control group. “We’ll monitor these families to see if they buy sets with V-Chips, and when they do, if they turn them on,” Woodard says. Results of the study won’t be available until the end of the year.

Annenberg researchers also are concerned about parents’ lack of awareness when it comes to the good shows. Only 35 percent of parents surveyed were familiar with the broadcasters’ E/I designation, and only 6 percent could recognize the E/I symbol that’s flashed in the left-hand corner of the screen for the first 15 seconds of the show. For the uninitiated, E/I stands for educational/informational, the rating programmers give shows that purport to have educational content.

The E/I designation—and which shows get it—has become more important to broadcasters as a result of the “Three-Hour Rule,” issued by the Federal Communications Commission in 1996. The rule requires broadcasters to air three hours of E/I programming for children per week if they want their yearly licenses to receive an expedited review. It was designed to strengthen the Children’s Television Act of 1990, the first legislation to call for educational programming. But the initial legislation included little oversight, and broadcasters stretched the definition of educational to include such questionable claims as that The Jetsons taught young viewers about life in the 21st century and The Phil Donahue Show taught teens about teenage prostitutes. “They could put up any show and claim it was educational, and no one knew until after the license applications were processed,” Jordan explains.

The 1996 rule requires that broadcasters’ reports be available on a quarterly basis; since then, some of the most egregious claims have been dropped. But a few others still crop up in their place. Jumanji, a syndicated show based on the movie version of Chris Van Allsburg’s children’s tale, was listed as “illustrating how characters survive the jungle by being creative and athletic,” the researchers note. Super Mario Brothers, a show based on the video game, was listed as “illustrating good versus evil … by showing the bad side of greed.”

In their study of the impact of the Three-Hour Rule, also released last summer, Jordan and her colleagues viewed three episodes of each show that was awarded the E/I label by its producers. Basing their evaluations on criteria developed with the help of a star-studded advisory panel that includes social activist and author Jonathan Kozol, popular children’s author Paula Danziger and Harvard law professor Charles Ogletree, the researchers judged each show.

They examined whether its lessons were clear, integrated into the story and accessible to children of the target age. Using that criteria, 33 percent of last year’s E/I programs were judged to be “highly educational,” 46 percent were “moderately educational” and 21 percent were “minimally educational”—similar to the results they got the prior season, the first year in which the Three-Hour Rule was in force. Jordan is pleased to note that the researchers found very little violence among the shows stamped E/I. “That was one of the most hopeful findings,” she says.

In their report, Jordan and her colleagues noted that most stations were meeting the three-hour requirement—and some stations offered even more programming. Fox, for instance, broadcast six hours of educational shows, including Magic School Bus, Popular Mechanics for Kidsand Bill Nye, the Science Guy.

The truth is that roughly half the E/I shows—and the vast majority of those broadcast by the major networks—deal with social and emotional issues rather than academic fare, and these are among the most popular. ABC’s popular Saturday morning lineup, “One Saturday Morning,” for instance, includes Pepper Ann and Recess, both developed in response to the Three-Hour rule. “In Pepper Ann the main character is female, and she is a smart individual,” enthuses Kelly Schmitt, a research fellow and author of the report on the Three-Hour Rule. “Her mom is single and the show tackles real issues that some kids go through—her mom dating, for example.”

The researchers express disappointment in the E/I shows like NBA Inside Stuff, which offers few salient lessons, and doesn’t seem to be improving from season to season. “It’s frustrating to see this show remain at a standstill,” says Jordan. “Children can learn through sports about working as a team and about statistics,” she acknowledges, but she doesn’t see any lessons conveyed by the show. “It’s a missed opportunity.”

Even Captain Planet, a Nickelodeon show devoted to teaching environmental lessons, does not escape Jordan’s careful critique. “It has a lot of action and adventure, good guys and bad guys. Sometimes the exciting music and action obfuscates the lesson,” she complains. Still that show received generally high ratings from the group.

Another positive effect of the Three-Hour Rule is that more programmers are consulting with educational experts to make sure their messages are getting across effectively. Still, with all the progress, Jordan warns that broadcasters shouldn’t be left unmonitored. “In this competitive environment there are so many incentives to produce pure entertainment that it’s important for academics, parents and advocacy groups to stay on top of what’s happening,” she says.

Just how to help parents get more involved in what their children watch is a subject of increasing concern to Jordan. “It’s clear to me that even if broadcasters produce good programming, it doesn’t make a whit of difference if parents and kids don’t know about it and can’t find it,” Jordan says. “Good shows are not promoted and regulations are not widely understood.”

So increasingly Jordan’s team has turned off the tube and ventured directly into viewers’ living rooms to conduct in-depth interviews with parents. “We want to know what’s happening now,” Jordan explains. “Are they concerned about what their children watch? Do they direct what they watch? We want to know whether and how parents are putting themselves between the children and the TV set.”

Her litany continues. “We have to understand the obstacles in getting families familiar with regulations. Why is it they don’t pay attention to the details? Why haven’t they heard of the highly educational shows like Histeria! and Bill Nye, the Science Guy? Do they let school-age children make their own viewing decision? Do they think it doesn’t make a difference what children watch?”

Look for the answers to those questions in future studies.

Leslie Whitaker last wrote for the Gazette in June 1998 on Broadway producer David Stone C’88.

SIDEBAR

What’s It Rated?

The Telecommunications Act of 1996invited the broadcasting industry to come up with a voluntary ratings system that could be used in conjunction with the V-Chip technology to block undesirable programs. Also known as “TV Parental Guidelines,” the ratings were established by the National Association of Broadcasters, the National Cable Television Association and the Motion Picture Association of America.

The left-hand corner of your screen is the place to look for ratings, which are flashed on the screen for the first 15 seconds a show is on the air. Because the rating system is voluntary, not all shows are rated. Ratings also can be found in most television guides and local newspaper listings.

The ratings characterize the shows based on target age or content.