Architect Barton Myers’ designs set the stage for art and life in the city.

By Virgina Fairweather

Barton Myers GAr’64 lives on a mountaintop, but—in contrast to the public image of architects from the imperious Frank Lloyd Wright to today’s media celebrities (not to mention Ayn Rand’s fictional Howard Roark, who would rather blow up his building than see his principles compromised)—there is little of the Olympian about him. No haughty gatekeepers are to be found at his home overlooking the Pacific. He greets a visitor wearing worn sweats, and prepares espresso in the kitchen. There is something Southern at work—perhaps a relic of Myers’ upbringing in Norfolk, Va.

Hospitality and good manners overlay, even mask, Myers’ intellectual curiosity and obvious intelligence. He has the credentials, along with the accolades and honors, to force his way, but those who have worked with him speak of his collaborative approach, his willingness to listen to everyone on the project team, as well as about his extraordinary talent.

Myers’ house, on a remote mountain site in California, was featured last year in an article in The New York Times. It is really three buildings—his studio, the living quarters and the guest house—that step down the steep slope, all similar oblong blocks of concrete, steel and glass. Two have water sitting on their flat roofs. The uppermost building is the studio, where Myers works three or four days a week, commuting with his wife Vicki, who is CFO of the firm, to Barton Myers Associates in Beverly Hills the other days. From the studio, one sees the successive reflecting rooftop pools and, in the distance below, the Pacific Ocean—framed on both sides by mountain ridges.

This esthetic effect has a very practical purpose. The site is covered with highly flammable brush, and the steel and the water are there to deal with fires. The rooftop water reservoirs are equipped with pumping systems for firefighting. There is glass everywhere, the mountains and trees visible from every room at every level, but across the front of each building are massive rolldown steel doors, furled but ready to shut the houses down tight in minutes in case of fire. Exposed hydraulic rolldown door mechanisms stretch across the ceilings inside. The walls and floors are fireproof concrete, albeit with a soft finish. Myers says that “one’s design has to say something about the technology of the day,” and his house is an emphatic example. But in spite of the austere materials, the fireplaces, books and artwork convey warmth and livability.

Myers’ other most recent high-profile design is as highly public as his house is distinctly private, but both structures illustrate some signature themes in his work, including an awareness of what he calls the “elegance of engineering and the potential applications of technology” (learned, he says, from his experience as a graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy and jet pilot) and an abiding interest in integrating a building with its larger context.

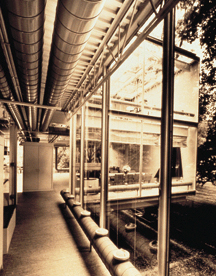

Still, the contexts could hardly be more different. The New Jersey Performing Arts Center (NJPAC) sits on the opposite coast from Myers’ house, in a tarnished urban industrial city—Newark, N.J. Here are the same exposed steel beams and acres of glass, but, rather than nature, they frame aging factories and bridges, small urban parks and the far-from-pastoral Passaic River. The arts center combines the technological excellence essential to theaters, an exploration of the uses of exposed steel, and, above all, Myers’ sensitivity to integrating the architecture with the environment.

Myers’ journey toward architecture began in Norfolk, where his roots go back to the 18th century. In 1790, Moses Myers, one of the first Jewish settlers in Virginia, was successful enough to build a large brick house. The Moses Myers house is now a museum, a graceful survivor of the general Norfolk urban-renewal demolition spree—and a possible inspiration for the future architect’s choice of profession. Another model was Myers’ grandfather, a building developer and planner who created several of Norfolk’s major gardens.

Photo: Futagawa

But as a young man, Myers recalls thinking that the people he knew who were planning to become architects were “a little weird” and instead entered the Naval Academy, where he received his undergraduate degree, training as a pilot. The immersion in technology was a good thing, he thinks now. Systems engineering, critical-path planning and military organization can be very useful for an architect, he says.

While serving in the Air Force, Myers was stationed for a time at the University of Cambridge in England. It was there that he decided to become an architect, fascinated by the combination of old and new structures at the university town and at Oxford. Between flight missions, Myers took courses and applied to graduate architecture programs back home. Among the few available at the time, Penn’s reputation was at a peak. So at age 26, he entered the Graduate School of Fine Arts.

He enthuses about the “giants” then in residence, notably then-Dean G. Holmes Perkins Hon’72, architectural icon Louis I. Kahn Ar’24 Hon’71 and Robert Venturi Hon’80. He also singles out Ian McHarg, emeritus professor of landscape architecture and regional planning, as a “great modern thinker on a par with Rachel Carson in terms of changing environmental thinking in this country.”

In the early 1960s, Myers says, Philadelphia was at a crossroads, linking architecture and urban renewal, and the official response, led by city planner Edmund Bacon Hon’84, was infinitely more humane and thoughtful than what he had seen in Norfolk. His Penn mentors were trying to “keep the old and question what the new architecture would look like,” and instilled in Myers the importance of the architect’s responsibility to “the public realm.” Philadelphia itself was “rich in ideas,” Myers recalls, a remarkable place that sparked his interest in cities and the role of architects as one that is “tempered by the circumstance and context in which one builds.”

At Penn, his design-studio classes focused on urban-renewal projects for the city of Philadelphia—“tough urban work,” Myers says. The idea of integrating the old architecture with the new echoed what he had seen at Cambridge and Oxford, but here the social issues were compelling. Architectural schools reflect the feelings in their cities, and Philadelphia was then a city of hope, says Myers. Afterward came the riots and “dark years,” he adds.

Part of the decline, in Myers’ mind, was the University’s neglect, even rejection, of Louis Kahn—a “remarkable, inspirational” man who was primus inter pares of Myers mentors. It still pains him that, when the fine-arts school’s new building (now Meyerson Hall) was constructed in 1967, Kahn was not chosen to design it.

Kahn’s influence on Myers continued after his graduation in 1964. He worked for him for several years, on such stellar projects as the Salk Research Center in Southern California and the capitol building in Dakar, Bangladesh. In 1968, seeing Philadelphia’s fortunes fade, Myers decided to start his own practice in Toronto, with A.J. Diamond.

The firm’s impact on Canadian architecture was extraordinary. A Canadian newspaper referred to Myers as the “unofficial godfather” of much of Canadian architectural design. His work there covers the range of urban planning and design, large and small buildings, public and private structures. He designed his own residence, using exposed steel and other industrial components, and his Wolf house, built in 1974, was recently cited as the Canadian design that “most anticipated the 21st century.” Myers also designed museums, art galleries, and hosts of university and other public buildings in Canada. His urban work focused on “infill buildings”—housing and other structures that were an attempt to “knit the urban fabric together, to enhance the city.”

By 1980, he had more assignments in California than in Canada and when UCLA offered him a professorship, he moved back to the United States. However, it was one of his Canadian projects—the Citadel, constructed in 1976, for which Myers won a design competition—that has led to his current pre-eminence in the highly specialized field of designing for the performing arts.

Gary Hack, current dean of the Graduate School of Fine Arts, says that much of Myers’ theater work derives from this “wonderful” building in Edmonton, Alberta. Myers “continues to experiment with moveable/changeable spaces for theaters driven by acoustics and the technical needs of different kinds of performances” in his theater work, Hack says. In a larger sense, his designs show how architecture works as a setting for the “drama of human life.” Hack cites a “magnificent” housing union Myers designed for the University of Alberta back in the 1960s. The structure has a quarter-mile glass atrium, with classrooms on the upper level, that shows “people acting out their lives” as they go to class, chat in the halls, and move from one level to another. The idea of people looking in and out of a building—interacting through the walls—is a theme throughout Myers’ buildings.

Connecticut-based theater consultant Richard Pilbro calls him “one of the finest theater architects in the U.S. today.” With his design for the Citadel, which has a 700-seat main auditorium, a 300-seat theater and a 250-seat lecture hall, Myers brought back the late-19th century idea of the importance of intimacy in theaters, adding “great individuality and detail,” he says. In the mid-1980s Pilbro worked with Myers on the Portland Center for the Performing Arts, and then in the early-1990s on the Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts, and the two got along “like a house on fire,” he says.

The Portland theater, Pilbro says, has an “enormous wealth of detail, a lush mix of timber and wrought iron that echoes the city’s bridges and architecture.” That theater seats 900 and is still “intimate yet invigorating,” says Pilbro, who works with architects on the functional planning and technical-equipment side of theater work. He calls Myers’ Cerritos project “revolutionary.” For this site, south of Los Angeles, he designed a theater with an auditorium that can be used for five different types of performance and audience sizes by “moving large chunks of architecture about,” says Pilbro. Not only can Cerritos be acoustically modified for performances from rock concerts to dramas, but the auditorium can be configured to seat as many as 1,950 people or as few as 950.

Myers himself says that Cerritos has been “tremendously successful,” and he is surprised there haven’t been more performing arts centers like it. Architecture for the performing arts can be the most satisfying kind of work, he says. “You are bringing people together—artists and audiences,” and you get “an immediate thank-you from both.”

(Myers got a very public thank-you when the late Frank Sinatra opened the Cerritos Center. Sinatra said the auditorium was the “most beautiful he’d ever been in,” and even called for the architect to stand and be recognized. “Sinatra was probably put up to it,” Myers says, in a self-effacing manner, but he seems pleased to tell the tale, nonetheless.)

“In all architecture, one needs to think about the place, the context and the program—the needs,” Myers says. For theater work, the needs are complex and many other experts—acousticians, lighting specialists, the artists themselves—are part of the process. “You have to listen, then translate all those needs into a building that meets expectations.” He likens the architect’s position to that of a movie director. “You have to have great people working for and with you, but you have to both listen and filter out what they want.” Myers’ ideas about responsibility to the city, his concern about the social implications of architecture, play a role here, too. In designing performing-arts centers, he says, the architect helps “unite a diverse population in a common experience.”

The $80 million New Jersey Performing Arts Center, which opened in 1997, has been hailed for its strong urban-planning elements and potential for revitalizing the city. Plus, as Lawrence Goldman, CEO of NJPAC says, “it’s a knockout.” Never in his 30-year performing arts career, Goldman says, has he seen such a reaction. “People who have never noticed design in their lives don’t want to leave the building,” he says.

Myers sees similarities between Newark and his native Norfolk. Both cities are about 300 years old and both lost their economic underpinnings: Norfolk’s in shipping, Newark’s in industry. However, Norfolk’s building stock was destroyed in the urban-renewal effort. In Newark, says Myers, the “wonderful” old buildings survived riots, social unrest and attempts at renewal.

The design and the materials used for NJPAC pay homage to the city’s industrial past. “There is no marble,” Goldman says, pointing out the absence of the stereotypical symbol of grandeur. Instead, “Barton used ordinary materials—glass, wood and steel.” In the main lobby, steel beams frame older red brick buildings outside, and the interior lobby walls are painted a brick-like shade that echoes what’s outside. Glass lobby balconies heighten the see-through effect typical of Myers’ buildings, that of passers-by participating in the events inside.

Gail Thompson, an architect herself and head of design and construction for the project, was a member of the team that selected Myers as architect. “Barton spoke eloquently about urban architecture” and wanted to combine warmth and intimacy in the building with civic pride, she recalls. The completed building is integrated with Newark. “There are interesting frames of the city everywhere.” Myers, she says, was “not an architect flying around with his own idea looking for a place to land it.”

If choosing Myers was easy, working with him was even better. A very collaborative architect, says Goldman. “Some architects tell the client to go away and wait for the final design.” Not Myers. “He understood the budget, helped cut costs without shaving the esthetics,” says Goldman. But if his design vision was thwarted, Myers’ jutting eyebrows “quivered.”

Nancy Hamilton was project leader for Ove Arup’s New York office, the principal engineering firm for the center. Hamilton has worked with “dozens of architects,” she says, and this was the best experience in her career. “He is a master architect, very talented, knows how to deal with unusual ideas.” Myers worked with her on an innovative steel-cable system that supports and frames the sky through the top of the copper rotunda. Working on NJPAC with Myers was “six years of passion,” she says. “It’s not always like that.”

Dr. P. Roy Vagelos C’50, former chairman of Penn’s board of trustees and co-chair of NJPAC, is another Barton Myers fan. He cites his “impressive” architectural approach to the problems posed by the Newark site, including a high urban-noise level, which Myers addressed by incorporating an acoustic barrier between each of the center’s components. “We all loved his plan” to deal with a multi-purpose structure by making two theaters, one large and one small, and each able to be converted to different performing arts demands, Vagelos says. Myers did this in large part with movable projections of wood that look “wonderfully warm—like being inside a cello,” he adds.

These devices are workhorses: They can adapt the acoustics to the needs of a symphony orchestra, a rock concert or a ballet. They can redirect reverberations and conserve sound. For a symphony, retractable projections over the orchestra keep sound from escaping to the domed ceiling or up the fly tower. Similarly, vertical wood panels at the back of the stage can be rotated or rolled away to change the acoustics for a particular performance. The acoustics in Prudential Hall, the main auditorium, have already made (very short) lists of the best in the country. Myers credits Russell Johnson, of Artec, a New York firm that has done several other concert halls on those same lists.

NJPAC has won dozens of architectural awards for Myers. Critics have generally praised the building as well, though at least one had a quibble about the lobby. How much can critics affect an architect’s business? A lot, says Myers. He thinks there is a “board of control” made up of journalists, mainly for the New York press, and some museum directors, who influence the selection of architects for major works. In Myers’ opinion, most architectural writers are focusing right now on a handful of people who might be called “artist/architects.”

However, in the day-to-day search for business, Myers says he’s been “pitching for 30 years, and still can’t figure what appeals to whom.” He does see a trend toward the selection of “corporate type” architects. There are more large architectural firms, and when many clients are large corporations, “they want to hire architects who look like them.” He sometimes thinks he can’t bring enough “vice-presidents” to the all-important client presentations. By contrast, when he got out of architectural school, the “last thing I wanted to do was work for a large firm,” he says.

Today, even performing-arts centers are sponsored by corporations, whose representatives play an important role in the selection process. Myers ruefully recalls wearing his best Armani suit to one presentation, only to be judged a “hippie” because one of his slides showed him at work in a T-shirt. On the other hand, Myers’ low-key manner was a great asset for NJPAC’s CEO Goldman. Other finalists for that job arrived with their respective “entourages,” while Myers came alone. Similarly, the New Jersey architectural selection team was impressed by Myers’ informal office, compared with those of the other candidates. In fact, says Goldman, Myers has no “office.” The 20 or so staff people work in one large space at the firm’s Beverly Hills building.

GSFA Dean Gary Hack tends to agree with Myers about the corporate trend. He thinks the architectural profession is “bifurcating” into small design studios and an increasing number of very large firms with 400 or 500 architects. These huge firms will do everything—design, planning, corporate logos, finance, real-estate advice and construction supervision.

What’s ahead for Myers? He wants to be diversified, but “always wants the firm to be designing at least one theater—they are exciting work.” An as-yet unfulfilled ambition is to design a stadium. He thinks stadiums are “great theater” and need to move closer to that concept in their design.

In the housing arena, he feels he has made a real difference, especially in Toronto, where he won the city’s first Arts Award, mainly for his firm’s urban-planning and housing work. He’s come full-circle in that area with a housing project in Cincinnati, which promises to be an extension of his early “urban infill” work. The project is intended to bridge the gap between the community and the University of Cincinnati by providing housing for 800 graduate students and stores.

Myers is also intrigued by a new niche. Calling himself the “plastic surgeon” of Beverly Hills, he is doing “remarkable” conversions of existing buildings. Everyone in the entertainment industry wants a Beverly Hills address, says Myers, and his firm is designing “wonderful new facades, using lots of glass.” The cost of these conversions is half the price of putting up a new structure with the requisite address.

Myers would also like to work in the city where he learned about cities—Philadelphia. Last spring, he was back on campus as a visiting professor at GSFA. Students learned an “immense amount about designing for the performing arts” from him, says Dean Hack. They also learned about the architect’s responsibility toward the city. In Myers’ studio classes, students focused on solving design problems related to Newark’s Performing Arts Center Master Plan. Just as Myers learned about Philadelphia’s urban design problems 30 years ago, his 1999 students at Penn got a similar message about the social implications of their work in cities.

Virginia Fairweather writes frequently on architecture and engineering.