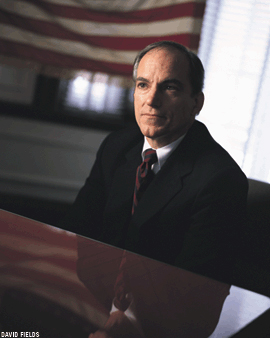

The new director of the Fels Center is a renowned criminologist with a zeal for finding out what works—and using it.

By Samuel Hughes | Photography by David Fields

Back in the summer of 1971—the Monday after the New York City Police headquarters had been blown up by the Students for a Democratic Society, to be precise—a bearded young Conscientious Objector named Lawrence Sherman walked into the office of his draft board. He had just finished a nine-month urban-fellowship program in the city, and the questions posed by the draft board involved what sort of public service he would be taking on in lieu of the military.

“I want to work in the New York City Police Department,” said Sherman.

“Good,” replied the man in charge. “You might get killed. Approved.”

As it turned out, Sherman almost did get killed on several occasions, and would, as an undercover scruff investigating police misconduct, get himself “thrown out of some of the finest police stations in New York City.” All that is a little hard to imagine today, as he sits in his office on the second floor of the Fels Center of Government, dressed in a dark blue suit and exuding a cheerful, vigorous respectability. After all, he is Dr. Sherman now, the Fels Center’s impeccably credentialed new director, the Albert M. Greenfield Professor of Human Relations and, arguably, the nation’s most influential criminologist, lauded by a broad coalition of scholars and top cops. But at 50, he has lost neither his appetite for engagement nor his deep-rooted appreciation for what Quakers refer to as the “life of the spirit.”

“The real paradox for me is that I’m from that tradition,” he says of his spiritual upbringing, “yet so interested in government.” He hints at a smile. “I guess I’m the product of Calvinist and Puritan backgrounds, and that probably explains why I’m here to make the government more Quaker-like.”

Criminology is not the traditional proving ground for academic government centers like Fels, and Sherman’s decision to shift his focus from the former to the latter surprised some of his colleagues. After all, he had built the criminology department at the University of Maryland into a top-ranked powerhouse during his 17 years there, and even since arriving at Penn in July he has managed to get himself elected president of the International Society of Criminology, nominated for the presidency of the American Society of Criminology, and awarded the ASC’s prestigious Edwin H. Sutherland Award for outstanding contributions to criminological knowledge. But coming to Fels was both an “intellectual evolution” —stemming from his work for Congress evaluating anti-crime programs—and a natural extension of his long-held desire to help “make cities safer and more viable economically.”

“If you want to deal with inner cities, you’ve got to get beyond the criminal-justice system,” he says. “And when I heard about a place that had a history of local and state government as the focus for its graduate program, and that also attracted really talented people who wanted to get things done in the world—as opposed to really talented people who want to do research—it just seemed like the right transition to make.”

It’s also directly related to that Alfred P. Sloan urban fellowship he embarked on three decades ago.

“If you ask me all the reasons why I came here, that may be the most important one,” says Sherman. “I think if I hadn’t been able to start my career in the New York program, coming right out of the University of Chicago [where he earned his first master’s degree in social science], I wouldn’t have learned and become as passionate about these urban issues as I did.” He thinks back to the weekly seminars with cabinet-agency directors—when “all of these functions of government were laid out on the table and kicked around for three hours over sandwiches and beer”—and suggests that the weekly colloquiums held at Fels for most of the past two decades are “exactly the same thing.”

“For me,” he adds, “it’s almost like coming home.”

“The question in scientific terms is: ‘Did program X cause result Y to occur?’” Sherman was telling the incoming Fels students last fall. “And as any scientific question has to presume, there is a methodology to answering that question—a method of understanding how we know what we think we do. And that method is something that needs to be much more central to government thinking—not in an academic way but in an accounting way, in a way that looks at these positive liberties much the way an accountant would look at cash.”

An interesting metaphor, though Sherman’s preferred analogy is medicine. Even in a clearly delineated field like that, he points out, where the linkage of cause and effect can be undeniable, doctors don’t always follow the research-based guidelines recommended by the National Institutes of Health. Whether it’s because they’ve never heard of the guidelines, or they’re too busy to read them, or they disagree with the recommendations based on their own experience, or because their patients object—when the best research is ignored, the real loser is the patient. The lessons for police chiefs and heads of government are obvious.

“The problem of conquering emotional or least-resistance-based decision-making with rational evidence is an enormous one,” says Sherman a few weeks after the Fels orientation, “and the fact that it’s widespread in medicine proves the point.

“The long-term question,” he adds, “is: Will we then take the next step, which is to spend money on surveillance systems—that is, ongoing indicators like crime trends—much the way that surgeons are now tracking the outcomes of operations on a case-by-case basis? It’s not just the randomized trials alone; it’s not just strong cause-and-effect evidence from published journal articles; it’s combining that with your own local data to see whether you’re getting the most out of that information, or whether that information itself needs to be enhanced by some previously unspecified variables. And that would be true of garbage collection, improving school performance, air pollution—all of these things can be subjected to a much more rigorous evidence analysis.”

Sherman’s Franklinesque emphasis on evidence-based programs is “pragmatic in the best American tradition,” says Dr. Samuel Preston, the Frederick J. Warren Professor of Demography who serves as dean of the School of Arts and Sciences (where Fels finally has a home after years in the unlikely locale of the Graduate School of Fine Arts). “For many years, public policy relied upon philosophy of one sort or another, rather than on detailed investigations of what was happening on the ground. And we’re in the midst of a revolution in public policy that is using one kind of data or another—preferably data that derives from experimental design—to investigate the importance of various programs.”

Having the data does little good if it isn’t put to use, of course; and that takes informed leadership. The challenge of the 21st century, Sherman told the incoming Fels students, “is to combine what works with who leads.”

The Fels Center was founded in 1937 by Philadelphia philanthropist and businessman Samuel Fels, who had seen enough corruption and incompetence in local government to want to do something about it. The stated object of its Master’s of Government Administration program is to prepare students for “leadership in government service, nonprofit and social-service organizations, and organizations closely associated with the public sector,” and its 12-course program revolves around finance, politics, economics and management. First-year students serve as interns with various government agencies and organizations, and attend the same sort of weekly colloquiums that so inspired Sherman during his urban-fellowship days in New York. Fels had dropped the colloquiums during the difficult interregnum period that followed the resignation of former director James Spady in January 1996, but Sherman is intent on bringing them back. He’s also in the process of revamping the curriculum, with the help of a “very insightful and thoughtful committee representing people from lots of disciplines.”

“Larry’s got a particular take on what a public-policy management program should consist of,” says Preston, “which is somewhat different than that of [Princeton University’s] Woodrow Wilson School or [Harvard University’s John F.] Kennedy School, where there’s a lot of economics and somewhat more theoretically oriented work. Larry is very, very empirical in his approach to the world, and his whole point is to use evidence on what works and what doesn’t work, under what circumstances, to structure programs, particularly in state and local government.”

“Everybody’s talking about results,” says Sherman. “[Pennsylvania Governor] Tom Ridge, [President] Bill Clinton—they all say we need to stop governing by ideology and govern by what works. But if we can’t agree on what our standards are, if we can’t agree on the technical methods for measuring results, we’re not going to get there.”

One should be forgiven for concluding—based on the observable evidence, of course—that Larry Sherman has always been precisely what he appears to be today: a highly empirical, ultra-pragmatic, can-do social scientist. In truth, he says, he was not particularly practical as a kid—though he did have a passion for military history, and an abiding interest in winning battles.

“I guess the real paradox is that I wasn’t very good at arithmetic or math,” he says matter-of-factly. “Even in high school I did pretty poorly in that area. And where I’ve arrived at in life is a view that the mathematics of policy are absolutely crucial. To me, the numbers are fraught with meaning, fraught with human suffering and potential for human quality of life.

“I don’t know quite how I got to that,” he continues, “but I think the answer is the social sciences. Because I was interested in the problems that the social sciences addressed, I was socialized into the methodology and framework of science per se—which I am convinced, despite all the postmodernist attacks, is the greatest tool that humans have ever discovered. And if we can just hold the course with the use of the scientific method, we will get to places that many people think we can never get to.”

And yet for most social scientists, as he points out, “the whole question of what policy-makers do with their research is not a burning question.” That it is for him is a “reflection of my personal background and my parents’ interests.”

Sherman’s mother, Margaret, is a lay minister on the board of the American Baptist Convention and the U.N. representative to the convention for 12 years; in 1993 her humanitarian work garnered the convention’s Edwin T. Dahlberg Peace Award (whose past recipients included the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and former president Jimmy Carter Hon’98). His father, Donald, was executive director of a YMCA branch in Newark, N.J., and later associate general executive of the Greater Washington, D.C., branch, and during the 1950s and ’60s oversaw the integration of those organizations. Larry grew up swimming and going to summer camp with kids from the poorest neighborhoods of Newark.

“From the time I was six,” he says, “I was conscious of advantage and disadvantage, and the issues of individual character as distinct from race or class stereotypes—because I had very good friends who were from very poor neighborhoods, and there were really nasty people who were from the better neighborhoods—and vice versa.”

The guiding value his parents imparted to him, he says, was an “abiding faith that we can do a better job of improving relations among human beings.” Which is why the opportunity of holding the Greenfield Professorship of Human Relations is his idea of “heaven” —in the sense that it’s an “opportunity to challenge the forces of hell.”

“In the sixties,” he adds, “my thinking was fundamentally moral. To know that my parents were marching with Martin Luther King to the Lincoln Memorial, and stood there listening to him give the ‘I Have a Dream’ speech—it was a moral confrontation of the highest order. It was worthy of Oberammergau or any of the Passion Plays for this great confrontation of good and evil. And the passage of the civil-rights legislation was undeniably of that character.”

Now, he says, having won those moral battles, “we were left with a host of technical problems”—including how to “maintain proper control of a police department” and how to keep a city’s economy viable “when it is by definition in American history a repository of poor people”—especially given the ability of middle-class people to get away from poor people. (For the record, Sherman now lives in Powelton Village.)

“These technical problems are not amenable to moral solutions,” he says. “And one of the disconnections that we have in the politics of cities is the use of sixties’ methods with nineties’ problems. The sixties’ method of protest—demonstrations, moral indignation —still has its place, but it won’t get us nearly as far as it did then. And what we’ve got to add to that, to put some meat on the bones of moral outrage over these conditions, is the technical mastery of solutions.”

During my interview with Philadelphia Police Commissioner John Timoney, I mention that I haven’t spoken with the subject of the interview in three or four weeks. He laughs.

“Larry’s kind of a hahd man to keep up with,” says Timoney in his Dublin-by-way-of-Manhattan accent. “If you don’t talk to him for three or four weeks, you’re about 17 ideas behind.”

It’s a trenchant observation. Since arriving at Penn in July, Sherman has jump-started a staggering number of projects and taken on a punishing number of responsibilities.

“He generates an incredible amount of activity,” said Sam Preston early in January, having spent the entire morning dealing with “Larry Sherman projects.” (He noted that the school’s director of development had told him that she needed “a full-time staff person in development for Larry Sherman,” though it’s also true that Sherman is quite adept at raising funds himself—a point not lost on the search committee that chose him.)

“He’s a whirlwind,” Preston added. “And all of it sensible. I mean, you find people who are extremely energetic and who go off in lots of different directions, and largely lack focus. Larry’s very focused.”

He’d better be. Consider:

- He spent much of January serving as lead co-chair of Philadelphia Mayor John F. Street’s public-safety committee, drafting the recommendations for the police department, the fire department, the prison system and the court system for the incoming administration. (“To see the University engaged from the outset with the new administration and in a dialogue with people from all over the city to shape these policies, is the right thing for the Fels Center to be doing,” says Sherman. “We’re happy to be as engaged as we can, because it only helps our students learn better how they can make a difference in making cities more viable places.”)

- He spent the first week of January in Canberra, Australia, where he is co-director of the Reintegrative Shaming Experiments, a series of experiments in “restorative justice”—wherein those who commit crimes have to repair the harm to victims through face-to-face discussions and mediation. Dr. Peter Grabosky, director of research at the Australian Institute of Criminology, calls it “the most significant piece of criminological research ever undertaken in Australia.” While it’s too early to say with absolute certainty that the process reduces repeat offenders, says Sherman, the experiments have already provided strong evidence “that people who go through the restorative-justice process increase their respect for the law; increase their respect for the police; and affirm their own personal morality in favor of obeying the law. And all the other research shows that that predicts lower repeat offending rates.”

As a result of his involvement in those experiments, Penn will be hosting a global conference on restorative justice in October 2002. It will also host the World Congress of Criminology in 2005—an indirect consequence of the December board meeting of the International Society of Criminology, which elected Sherman its president. (He is the third American to hold the top ISC post and the second from Penn, the first being the late Dr. Thorsten Sellin G’16 Gr’22 Hon’68.) - He has been meeting with state, federal and local legislators and business leaders to consider implementing a block-by-block “urban-extension” program (modeled somewhat after state agricultural-extension programs). The idea, he says, is to focus all resources on changing the culture of individual distressed blocks, one by one, rather than concentrating on single, broad-based issues such as education or jobs or drugs—since “all the evidence suggests that if you can change the culture of one block, all those things will come together at once.” He is in the process of trying to raise $6 million for a pilot study, and the evidence suggests that it would be unwise to bet against him. Jerry Lee, president of WBEB-FM in Philadelphia and a devoted supporter of Sherman for several years now, says he intends to “be a permanent giver of funds,” and has already donated a goodly amount of money to Sherman-backed projects. (“I think the guy walks on water,” Lee says simply. “He has the combination of brilliance, open-mindedness and the ability to make everything work. And he does not know the meaning of the word no. I tell you, if there’s any person in the country that can solve the problems of the inner city, this guy is it.”)

- In November, he organized a conference at Penn for the Department of Justice titled “The Corporate-Community Coalitions for Public Safety: The Role of Business in Building and Sustaining Safe Communities,” which featured U.S. Attorney General Janet Reno, Philadelphia District Attorney Lynne Abraham, Timoney, and a number of business and community leaders from around the country.

- He has been working on a proposal with Dr. Susan Fuhrman, dean of the Graduate School of Education and chair of Penn’s Urban Agenda Committee, to develop a new Center for Urban Innovation, which would be housed at the Fels Center. Although the idea for such a center somewhere at Penn had been discussed before Sherman arrived last summer, Fuhrman says the committee gave a “collective ‘Aha!’” when he joined the discussion, realizing that, under his guidance, Fels was the center’s logical home. It would, says Sherman, “allow the Fels Center to engage with all of the schools on campus that have a strong interest in urban research.”

“It’s all to the positive side of the ledger to have this much activity being generated,” says Preston. “And I think it’s going to result in a vast improvement in our teaching and research in urban areas.”

The benefits of being at SAS are not lost on Sherman.

“I’ve known for a long time that Penn had the best group of urban scholars in the world, and was personally acquainted with quite a few of them,” he says. “So the opportunity to work with them and be their colleague was very attractive. If I had been asked to direct Fels as an operation that was not close to the active life of this campus, I wouldn’t have been interested.

“In the long run,” he adds, “the system that needs to be created at Fels is a larger faculty in the School of Arts and Sciences who spend the majority of their time teaching at Fels. And that’s a matter of economics; it’s a matter of development; it’s a matter of building this place into what it has the potential to become—which in my mind is the finest graduate school of public affairs and leadership in the country.”

When Anthony Bouza became inspector in charge of planning for the New York City Police Department back in the early 1970s, he asked his predecessor to give him a full rundown of the planning division. He describes the response:

“He said, ‘There’s a kid there, you want to watch him. If you turn your back, he’s gonna take over your desk.’” The kid was Larry Sherman.

“I was very rapidly astounded by his brilliance; it’s just that simple,” recalls Bouza, who in 1989 retired after a decade-long stint as chief of the Minneapolis Police Department, having served as assistant chief of the NYPD for the Bronx before that. “I gave him one tough task after another, and helped him with anything he wanted to do. He was brash and aggressive and talented, but I was not threatened by him at all. I thought this was a talent to serve, and I was happy to serve it.”

Among those tasks was that of going undercover to investigate the very police department for which he was working.

“Try to imagine yourself at the age of 21 and 22—and this was in 1971, remember—and some maniac is telling you ‘I want you to go into the police stations in New York City and say, “How do I report police brutality? How do I report an incident of police wrongdoing or corruption?”’” says Bouza, the author of seven books on policing. “And really, that was not a safe thing then for a bearded, young, hippie-looking guy to do. Yet he did it.”

Sherman laughs it off now, noting that while the reaction was sometimes extremely hostile, nobody ever laid a hand on him. “Undercover testing in police procedures has a long and noble history,” he says, “and I was pleased to be a part of that tradition. It gives you a lot of respect for the undercover role, because you never know what can go wrong.” He later would train 500 investigators to conduct investigations on police misconduct, and would publish a book titled Scandal and Reform: Controlling Police Corruption.

For a guy who started off investigating police corruption out of a sense of moral outrage, Sherman has a pretty enthusiastic following in law enforcement.

“Very few people could pull it off,” says John Timoney, who a couple of years ago asked Sherman (then at Maryland) to advise him on ways to ensure the reliability of crime statistics in the Philadelphia Police Department, where the numbers had long been cooked. “And the reason he could pull it off is because he’s fair. He’s seen as objective, and at the end of the game, what cops want is somebody that’s fair. In policing, like it or not, there’s a huge gray area, and unless you’re knowledgeable in the nuances of policing, you’re apt to reach the wrong conclusions every time.” (Timoney, incidentally, says he is “thrilled” to have Sherman in Philadelphia, and the admiration is clearly mutual.)

Sherman’s sense of fairness helped him when he began carrying out his field experiments, including one on police responses to domestic violence in Minneapolis. Bouza, who gave him carte blanche to conduct experiments there, describes it as a “very, very hostile and resistant police department,” even though he himself “was imposing the necessity of doing social experiments.”

Whenever the police responded to a domestic-abuse situation, he explains, they were given a document with a randomly assigned specified response, and had to do whatever it said. Of the various responses—which included conciliation, arrest, excluding the batterer and telling him not to come back for 24 hours—the most effective proved to be arresting the batterer. The Minneapolis Domestic Abuse Experiment became a landmark study in criminology, and Sherman’s 1992 book, Policing Domestic Violence: Experiments and Dilemmas, won the American Sociological Association’s Distinguished Scholarship Award. More important is the fact that, as Bouza puts it: “The reason men are being arrested for battering women is because of Larry Sherman.”

Carrying out the experiments was anything but easy. “The difficulty is that when you try to persuade a police officer to select a treatment according to a random number, the police officer doesn’t want to do it,” explains Dr. David Farrington, past president of the American Society of Criminology and professor of psychological criminology at Cambridge University in England, where Sherman earned his degree in criminology in 1973. (He earned a second master’s degree and his Ph.D. in sociology from Yale University in 1976.) “Police officers think they know what the best disposal is. They don’t want to be told, ‘We don’t know the effects of these different policies and practices, and in order to find out, we need to do a randomized trial.’”

Medical researchers conduct such experiments all the time, Farrington notes, yet “very few people have managed to pull it off” in criminology. For that reason alone, he regards Sherman as the “outstanding pioneer of randomized experiments in criminology.”

“He did it because of his enormous energy and determination,” adds Farrington. “He believed things were possible that other people would have given up on.”

Sherman’s success also had something to do with the fact that he spent a lot of time in patrol cars. Not only did he build up a rapport with the police officers responding to complaints, but his presence discouraged fudging the results.

“He brought a tremendous rigor and discipline to on-the-street experiments,” says Bouza. “He’s the only [criminologist] I know who was willing to go into the streets.”

It paid off. In Minneapolis, Sherman recalls, “the middle management hated the police chief, and the middle management told the rank-and-file not to do it—but the rank-and-file hated the middle management! And so I could go right to the rank-and-file and persuade them based on face-to-face time.”

The challenge, he explains, is “essentially politics, and it’s no different from implementing a new educational policy or a new environmental policy. If you want to get something done, you can’t just issue an order and assume it’s going to happen.”

Convincing the rank-and-file to work with him, he says, often involves things like pizza parties and retreats “where we go to plan an experiment and can all go swimming at the end of the day—and then maybe after dinner, we might throw each other in the pool with our clothes on.” He calls it “bonding in the pool,” and explains that it’s “really a matter of treating people with the importance they deserve, because their discretion, their support—or lack of it—can make or break an experiment.”

Not all experiments and programs are created equal. In 1997, Sherman and his criminology-department colleagues at Maryland wrote a report for the National Institute of Justice examining the effectiveness of more than 500 crime-prevention programs funded by the U.S. Department of Justice. It was titled: “Preventing Crime: What Works, What Doesn’t, What’s Promising.” For most programs, Sherman and his colleagues found, there isn’t enough scientific evidence to evaluate them with any accuracy. As he told the House Subcommittee on Crime last July: “The dramatic growth in action funds since 1993 has been accompanied by almost no growth in evaluation funding, which is a guaranteed method for perpetuating ignorance.” He has been recommending that up to 10 percent of all programming funds be set aside for evaluation research.

Their review, coupled with the most recent data on violent crime, found that most crime-prevention funds were being spent where they were needed least; that most crime-prevention programs had never been evaluated; and that some of the least effective programs received the most money.

The 23 programs that don’t work include: gun buy-backs; military-style correctional boot camps; Drug Abuse Resistance Education (DARE) classes taught to school children by police officers; summer job programs for at-risk youth; home-detention on electronic monitoring; neighborhood watch programs; police counseling-visits to homes of couples days after domestic-violence incidents; and “safe and drug-free schools.” Sherman describes that last program as a “wonderful example of an emotion-driven, political response to polls that makes no sense from the standpoint of dealing with a problem of actual suffering,” since most American schools are “among the safest places on earth.” The half-billion dollars spent on it each year, he adds, could be “much better spent to prevent crime in early childhood, before people even get to school.”

The list of programs that do work include: Nurses visiting high-risk infants at home; Head Start-type programs with weekly visits by teachers to students’ homes; extra police patrols in high-crime “hot spots”; anti-bullying programs in schools; drug-treatment programs in prisons; and rehabilitation programs focused on offender risk factors, such as illiteracy.

The “promising” programs include community-based mentoring by Big Brothers/Big Sisters of America; community-based after-school recreation programs; and “enterprise zones.”

Most crime-prevention funds are being spent in low-risk areas, the report noted, since most of the formulas are based on population, not the per-capita level of violence in a given area. (“Half of all homicides in the U.S. occur in the 63 largest cities,” Sherman pointed out, “which house only 16 percent of the population.”) Put bluntly, he added, the formulas “put violence-prevention funding where the votes are, not where the violence is.”

Jeremy Travis, director of the National Institute of Justice in Washington, D.C., calls the report a “landmark review of the research literature” and a “point of departure on the policy debate on crime.” In the three years since it was published, he adds, “we still refer to the methodology, the rating system, the strength of the scientific conclusions and the organizational principles, which look at the prevention of crime as an outcome, as the result of interventions. That organizing principle continues to be very important. Larry Sherman is a guiding light in designing the intellectual framework for organizing a review of the literature.”

The report was “exceptionally influential with the Department of Justice,” confirms David Farrington. “It was excellent in bringing together a lot of evidence related to preventing crime, and very important because he developed a scientific method scale—the crux of the idea is that not all research is equally valuable. You have to take account of the quality of the research in assessing the contribution.”

Of course, sometimes even scholars disagree about what constitutes good-quality research. In December, for example, Sherman and John Lott, a senior research scholar at Yale University Law School, squared off on the subject of gun-control during PBS’ News Hour with Jim Lehrer.

Sherman, who has been a strong advocate of police programs designed to reduce illegal gun-carrying in urban high-crime areas (such as stopping cars for minor violations and searching them), argued that “the evidence shows that those efforts pay off enormously.”

Lott, the author of More Guns, Less Crime: Understanding Crime and Gun Control Laws, disagreed with his conclusions and his methodology. “Larry was trying to argue that the drop in violent crime may be attributed to the changing enforcement activities in New York City, where they’ve adopted the so-called ‘broken windows’ strategy,” Lott recalled in an interview. “The problem with the way people use that evidence is that we’ve been having a drop in violent crime across the entire country, not just New York. Large cities like L.A., Houston and so on have also had big drops, even though they haven’t changed their policing policies.” He believes that the crime reductions in places like New York are the result of the “huge drop in drug prices” (the result of cutbacks to drug-interdiction programs, which led to a surge in the availability of drugs), since drug gangs don’t have the same “incentives to go and fight each other in order to control drug turf.”

The difference between his approach and Sherman’s, says Lott, is that “Larry’s much more into the case-study-type approach, and I don’t find that completely convincing, because there are so many other factors that can have a bearing over time. It’s very difficult to go and disentangle whether or not that one particular policy—or some other policy that just happened to change at the same time—was responsible for the change that you observed. What I like to do—and it takes a little bit more time—is to study every place in the country, if possible, at the same time, because different places will adopt different types of laws or policing policies at different points in time. If you’ve got enough variation with enough places adopting the particular policy that you’re studying, you can hopefully begin to disentangle all the other possible explanations for why there was a change in crime rates.

“Larry is very careful for what he does,” Lott adds. “I’m just not very convinced that that’s the right methodology to use.”

Sherman is currently writing an article for the New England Journal of Medicine that he says “confronts the contradiction between experimental evidence on the effect of gun-carrying and the econometric models that Lott uses, which suggest that if more people carried guns there would be less crime. The experimental evidence says that if there’s less carrying, then there’s less gun crime, and I don’t think Lott’s evidence can distinguish gun crime very well from crime in general. The issue here is one that is central to the Fels curriculum, in that the leading public-policy schools—like Woodrow Wilson or the Kennedy School—tend to stress econometric modeling as the most rigorous research that you have in public policy. They tend not to stress experimental and program-evaluation evidence—in part because it’s a lot harder to do.”

Lott disagrees: “What he’s doing is not the same type of controlled experiment in medical trials, where you’re going to be monitoring somebody’s diet and be able to control all aspects

of that.”

“It’s not an either/or issue,” says Sherman, “but I think there is something to be said for the argument that you get firmer evidence from actually trying policies out than you can get from econometric modeling as a prediction.”

Back in Samuel Fels’ handsome brick mansion on Walnut Street—Sherman’s office was once the bedroom of Fels’ wife—I ask Sherman how much things have really changed since the 1930s, when Fels was complaining about “amateurs” working in city governments and politicians who didn’t always “have the public interest at heart.”

“I have a wonderful connection to Sam Fels,” Sherman answers, “which is that my first area of urban-policy work was corruption. And that’s what got Sam Fels into policy. His vision of trying to professionalize government wasn’t just an urban vision; he saw this as a suburban and local-government issue all over the state of Pennsylvania. It still remains the case that we have lots of people making policy decisions who are untrained in what they’re doing—in part because of Digby Baltzell’s thesis that Quaker culture doesn’t think that expertise and book learning is very important, and that doing the right thing is going to come from inspiration from the inner light, in direct communication with the Lord.”

Sherman pauses a moment, then adds, with a look in his eye that is both playful and dead serious:

“I’ve got my linear light in which the Lord is telling me that these are complicated problems—and that people had better learn something about it before they try to deal with it.”