Class of ’67 | The word cathartic has been used a lot by writers over the years, with varying degrees of justification. But when Charles (Chuck) Newhall III C’67 says that he “needed to write as a catharsis” and describes his recent book Fearful Odds: A Memoir of Vietnam and Its Aftermath as a “coping mechanism,” he’s being, if anything, understated. He’s also offering his story as testimony for others who have gone through the charnel house of war and are grasping for a lifeline.

On the surface, Newhall’s life could be seen as a shimmering success story. A decorated combat veteran (silver star, two bronze stars) of the 101st Airborne Division who fought his way through the bloody A Shau Valley, Newhall somehow survived and came back to prosper as a venture capitalist, co-founding New Enterprise Associates (NEA), serving as chair (now emeritus) of the Mid-Atlantic Venture Capital Association, and supporting numerous charitable organizations. The young man who, as a Penn English major, had dreamed of becoming a writer but saw himself as a wallflower at parties married an attractive debutante named Mary Washington (Marsi) Miller; together they had two children. But beneath the surface lurked some psychic carnage.

Newhall was born into a family steeped in military tradition—his great-grandfather had founded the Shattuck Military Academy, and his grandmother strongly encouraged his other dream: becoming a warrior. At Penn—where he enrolled in the ROTC program, served in an Army Reserve unit, and started a Special Ranger detachment—his military-school background gave him the authority as a freshman to command juniors and seniors. It was, he acknowledges, “awkward for a freshman English major to walk around the campus in camouflage fatigues, jump boots and a green beret,” with the ever-present “foot-long commando knife strapped to my waist.”

That knife accompanied him to Vietnam, where his warrior dream became an almost unspeakably brutal nightmare. He saw men die violently and suffer terrible wounds. He saw enemy corpses desecrated and knew that a similar fate awaited him should he be killed. After one successful and grisly ambush of a North Vietnamese Army unit, he writes, “we grab the heads of the NVA, decapitated by the claymores [anti-personnel mines], and set up a bowling alley on the jungle trail.”

But he does everything in his power to ensure that he’s not on the wrong end of a bowling tournament. Consider the time he went to check the body of an NVA soldier—who not only turned out to be alive but was raising his AK-47 in his direction:

I knock the rifle away with my left arm. My commando knife with its curved blade like an eagle’s beak is in my hand. I plunge the blade into his throat. He makes a croaking sound and shakes violently. He stinks of sweat and garlic and I have to hold his thrashing body down until he is still.

Or the night when he came across one of his own soldiers—asleep (aided by some marijuana) while on sentry duty:

I shove the barrel of my rifle down the asshole’s throat, through his gaping mouth, and hope to break his teeth. Simultaneously I drive the heel of my boot into his stomach … We stare into each other’s eyes as I lean on the cocked rifle and he starts to cry. He is only 18. I withdraw my rifle from his throat. He rolls over on his side, sobbing … The words come out as a whisper: “Why shouldn’t I kill you, douche bag? You were trying to kill me!” I draw my knife across his throat … A thought crosses my mind: Have I been in this country too long?

A week or so later he gets a letter informing him that he has been accepted into Harvard Business School’s MBA program. On the plane that takes him away from the A Shau, he finds himself wishing he had re-enlisted.

After earning his MBA, he immersed himself in work, first with T. Rowe Price and then with NEA, now the largest early-stage venture capital firm in the world. It’s fair to say that he was driven—and that he had learned some survival skills in the Army that carried over to his business career.

“The pluses are that I very early learned that shit happens, and you have to be prepared for it—you have to have a plan,” Newhall says. “If they come from the front, the back, or the sides, then you have to be prepared to react immediately. I can’t tell you how many times that saved me in business. But while you’re waiting for all this catastrophe to happen, you’re not a pleasant person to live with.”

Newhall’s account of the breakdown of his marriage brims with remorse. As he told his psychiatrist, “We were like two people punching each other … until both get knocked out, fall to the ground, and cannot get up. We each contributed to the destruction of our marriage.”

In March 1982, the destruction went further: Marsi killed herself, using the pistol given to Newhall by his grandmother. He was left with their two young children, memories, and guilt. She appears to have suffered from the bipolar disorder that ran in her family. Afterwards he found her diaries and a final letter to him that must have been devastating to read. But he doesn’t try to hide his own role in the tragic events.

“There’s no doubt that my problems helped to accelerate her suicide,” he says, adding that he knew something was seriously wrong when he “started dressing in fatigues and sleeping with an Uzi off-safety.”

“I knew there was something very screwed up with me, and I knew there was something very screwed up with Marsi,” he adds. “And we’d gone through all sorts of dead ends” trying to save their marriage.

Newhall survived Marsi’s death. He has remarried, though he acknowledges that his second wife, Amy, hasn’t always found him easy to live with, either.

His financial circumstances gave him access to top-flight mental-health care, including a psychiatrist who gave him practical advice: Stop dressing in fatigues and sleeping with an Uzi. Stop treating the children like young soldiers. Stop drinking. All helped—but only to an extent. Same with the medications he was prescribed.

“PTSD is the one form of depression that nothing works for,” he says. “It’s called TRD—Treatment Resistant Depression. I’ve been on the boards of all these neurology companies, and I’ve worked on solutions for PTSD, and I don’t know of a research program that gives much help. So you’re really back in a corner, learning how to cope with it, as opposed to finding the magic bullet.”

What probably saved him was the combative drive that had helped him in war.

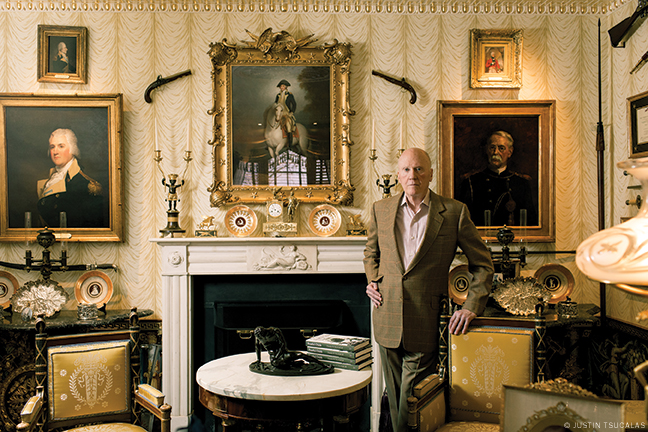

“I was too busy to let PTSD bother me because I had so many other distractions, if you will—business, children, writing, collecting, gardens,” he says. “So many people that suffer from PTSD just get derailed, and they sink into themselves and feel sorry for themselves—it’s like having your finger stuck in an electrical socket, and you’re incapable of movement. But you can’t let that happen to you.”

Newhall says he wrote Fearful Odds partly to “get this message out,” and he’s been gratified by the response to his self-published memoir, which includes letters and emails from other Vietnam veterans and their families.

“One person sent me an email saying, ‘Thank you for your book. It saved my life. I was going to commit suicide,’” he recalls. His website (fearfulodds.com) also lists professional organizations and articles for those struggling with PTSD.

Personal appearances with veterans groups and other organizations have had some mutually beneficial results as well. At one D Company reunion, “the husbands would get up and start telling their stories, and the wives would come up crying and thanking me,” Newhall recalls. He spoke at Edison High School in North Philadelphia, 64 of whose alumni were killed in Vietnam, and left that inner-city school, which still has a military program, deeply impressed.

These days a couple of other writing projects take up much of his time. One, tentatively titled “Dare Disturb the Universe,” chronicles his business experiences creating NEA. The other is about a different “coping mechanism” for war veterans: Brightside Gardens, a series of 54 “formal garden rooms” that he and Amy created on their property in the Baltimore suburb of Owings Mills. He says that book is both “very intellectual” and “intimately tied to Fearful Odds.”

“I think I’m at the most creative point in my life,” Newhall adds, then pauses. “But I am still fighting dark thoughts.”—S.H.