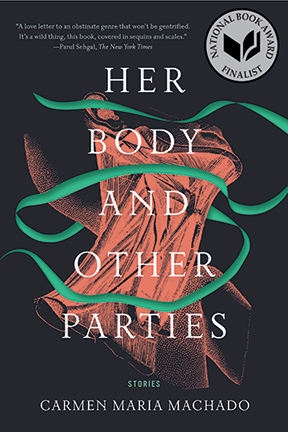

Carmen Maria Machado’s “weird, queer, genre-bending short story collection” was a surprise success—especially to her.

Last September, before Carmen Maria Machado’s first book had even been published, it was already a contender for the National Book Award. By January, it had won the National Book Critics Circle’s prize for best first book. In February, it landed the 2018 Bard Fiction Prize.

To list each accolade that Her Body and Other Parties has racked up in the past year—all the best-of-2017 roundups it appeared on, the many awards it won or became a finalist for—would take paragraphs. And along with that, there have been the deep-dive profiles, the trips all over the world for public readings, the heaps of books to sign.

“I certainly did not expect it,” Machado, who teaches in the creative writing program, says of her debut’s fast and obvious success. “Honestly, I thought I would be really lucky just to make back my advance. A weird, queer, genre-bending short story collection is not exactly bestseller material in any regard.”

But this particular weird, queer, genre-bending short story collection, with its feminist take on women’s lives and bodies, hit just as the #MeToo movement was igniting last fall. “Obviously there’s no way I could have predicted or been writing toward that,” Machado says. “But women’s lives have always been shitty. It just happens to be that we’re in a really bad moment right now, so I think people are looking for work that’s speaking to that.”

A book that catches fire the way Machado’s has isn’t only about good timing, though. “Her language is so carefully crafted, so mindfully put together,” says Julia Bloch Gr’11, the director of Penn’s creative writing program. “She’s not just a master storyteller—she’s also really brilliant at harnessing details and harnessing the unexpected.”

Readers have also been drawn to the genre bending and blending threaded through Her Body and Other Parties. At various points, Machado’s stories dip in and out of science fiction, queer theory, horror, psychological realism, fantasy, and fairy tales. It’s impossible to predict when a realistic story will suddenly turn apocalyptic or when a romance will veer into horror.

Machado kicks off the collection by reimagining an urban legend that she first encountered in a kids’ horror book. The original tale is only a few paragraphs long. Machado’s version, “The Husband Stitch,” turns it into a chilling, sexual, feminist allegory. It’s sprinkled with startling stage directions (example: “If you are reading this story out loud, force a listener to reveal a devastating secret, then open the nearest window to the street and scream it as loudly as you are able”) and incorporates a slew of other urban legends in the process of expanding on its original source, “The Green Ribbon.”

In “Especially Heinous,” Machado reimagines almost 300 actual episodes of Law & Order: SVU, packing them with alien sightings, doppelgangers, and ghosts who have bells for eyes.

She says her stories are often a mix of her own experiences, ideas that have been bumping around in her head, and, as is the case with both “Especially Heinous” and “The Husband Stitch,” her encounters with other media.

Whether she’s reading, watching TV, or even playing a video game, “I just think, ‘What is this story telling me both on purpose and not on purpose?’” she says. “I’m overly interested in what the story is telling me without intending to, because often it’s reflecting some thought process or prejudice or idea that the creator had without even realizing it.”

Machado compares a short story to a punch in the nose: with a quick jolt, it leaves you breathless and wondering what happened. She also sees the form as a laboratory—somewhere she can experiment with different genres, literary devices, and prose styles. “If you fail an experiment with a novel, that’s a lot of time lost,” she says. “With a short story, I can play around.”

She and Penn found each other in 2016. Machado had moved to Philadelphia a few years earlier with her now-wife, Val Howlett, who works for Running Press. Although Machado had an MFA from the prestigious Iowa Writers’ Workshop, she was adjuncting and working for the cosmetics store Lush.

On March 28, 2016, inside the Kelly Writers’ House arts café, she read her short story “Observations About Eggs from the Man Sitting Next to Me on a Flight from Chicago, Illinois to Cedar Rapids, Iowa.” Bloch remembers marveling over “the artistry of her work.”

The creative writing program had just gotten approval to add another fiction instructor, and from that night on, “we especially wanted to look at Carmen’s work,” Bloch says. “She ended up being such a great fit that we were then able to hire her. I can’t believe our luck—we were able to bring her into the Penn community just as her book was taking off.”

The fact that Machado often writes speculative fiction—the umbrella term for genres and sub-genres that have at least some fantastical elements—further thrilled Bloch. She says it’s something students had been requesting for years.

Machado has now piloted several speculative fiction courses and also taught a class on flash fiction. “She’s very good at drawing people out, and she gave us room to play as writers,” says Darby Levin C’19, who took Machado’s first speculative fiction class at Penn.

At the moment, Machado is deep into new risks of her own. She’s spending the fall semester in residency at Bard, working on a memoir about violence in same-sex relationships. It’s due out next fall, and she says it will have a nontraditional structure and be, more generally, “kind of a weird book.”

She’s also writing new short stories and has found herself increasingly drawn to horror. “What scares us and what we are afraid of is a reflection of cultural ideas and psychology,” she says. “Horror also has a quality of subversion to it that permits a lot of really interesting inquiry.”

“I think Carmen is part of a cohort of younger writers who are tapping into a need and a desire that readers have for more relevant depictions of experience,” Bloch says.

“She’s finding a lot of readers who might not have thought a National Book Award finalist was the kind of writer who could speak to them—not just marginalized writers and readers but people who might even be new to fiction,” Bloch adds. “There are a lot of people who have been wanting this kind of work for a really long time.”

—Molly Petrilla C’06