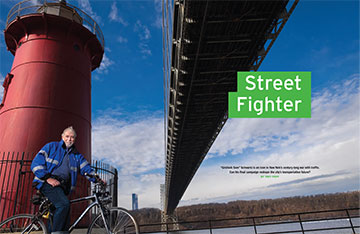

“Gridlock Sam” Schwartz is an icon in New York’s century-long war with traffic. Can his final campaign reshape the city’s transportation future?

BY TREY POPP | Photograph by Don Hamerman

It’s half past nine on a Friday morning and the Henry Hudson Parkway is wide open when Sam Schwartz GCE’70 receives his first GPS instruction. We’re speeding north out of Manhattan. Upper West Side brickwork flickers through the bare-branched plane trees lining Riverside Park. In two miles, intones the halting yet serenely unflappable voice of Default Female, bear right … onto I … Ninety-Five … North.

Schwartz pauses mid-sentence and cocks his head slightly. “I don’t like the way she’s going,” he says, in a mild Brooklyn accent. “I’m going to go a different way.”

New York may be bumper-to-bumper with drivers who know better than their GPS Sherpas, but Schwartz has a special claim to mastery, so we shoot past the George Washington Bridge. And glide along. Fort Lee slips by on the opposite bank—you can still buy “I Survived Bridgegate” T-shirts commemorating the traffic scandal that kneecapped Governor Chris Christie—replaced by swiftly scrolling views of the Hudson River Palisades. Everything’s moving smoothly when we hit toll-plaza signs flashing warnings of impending gridlock.

Yet it doesn’t materialize—at least nowhere in our path—and for a minute I curse my luck. Traffic jams are not my idea of fun, but how many times do you get to battle gridlock alongside the man who coined the term?

Schwartz, a fleet-minded Brooklyn native creeping up on 70 years of almost unreasonable devotion to New York, is better known as Gridlock Sam. The word first appeared in print in a 1980 memo he authored as the city’s chief traffic engineer, and though he has tried to share credit with a reluctant colleague, the coinage has clung stubbornly to him ever since.

“I’m pretty sure that the first line in my obituary is going to mention it,” he writes in his new book, Street Smart: The Rise of Cities and the Fall of Cars, which splits the difference between memoir and urban-transportation manifesto.

That’s a fair bet. But it will leave plenty of nuggets jostling for the second line.

Ever wonder about those Manhattan street signs warning DON’T EVEN THINK OF PARKING HERE? Schwartz’s idea. Same goes for their Koch-era cousins: NO PARKING, NO STANDING, NO STOPPING, NO KIDDING. (Both were deployed extra high up on poles to discourage theft, but nonetheless became coveted collector’s items virtually from their debut.)

Indeed, a cheeky obituarist might be tempted to tell Schwartz’s life story entirely through traffic signs. One of his personal favorites adorns the Carroll Street Bridge, one of four remaining retractable bridges in the United States, whose sliding wooden deck spans the Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn. After orchestrating its restoration in the late 1980s—against the will of city budget honchos who wanted to tear it down and build a modern replacement with federal money—Schwartz hung a placard reading: “ORDINANCE of the City | Any Person Driving over this Bridge Faster than a Walk will be Subject to a Penalty of Five Dollars For Each Offense.”

In 1984, as traffic commissioner, Schwartz had lines painted and signs posted around Brooklyn’s Park Circle rotary—one of the borough’s busiest intersections—designating a horse crossing, to help the animals access Prospect Park trails from a nearby stable. “It’s about time,” he told The New York Times. ‘‘After all, horses were here way before cars.’’

That rhetoric matched his record—and it suffuses Street Smart, which begins with an impassioned ode to the history of public roads that laments their 20th-century domination by private automobiles. Four years before the horsewalk, Schwartz had built curb-protected bicycle lanes on the avenues linking Central Park to Washington Square. Today, urban planners have a catchphrase for this ethos: “Complete Streets”—and Broadway Avenue has become an exemplar. When Schwartz tried it, it was too far ahead of its time to last.

Yet he could be equally creative in his efforts to improve life for drivers. (Which, of course, was the point of cracking down on parking scofflaws, whose lane-blocking ways exasperated hundreds of people behind them.) Befitting a bureaucrat who boasts of committing “low-level sabotage” during his peonage in the Traffic Department—“I would widen a sidewalk to a decent size here. Eliminate a parking lane there”—Schwartz’s street-sign oeuvre occasionally had a cloak-and-dagger side. To this day, some Manhattan curbs are posted with No Standing signs whose exemption for “authorized vehicles” is governed by the cryptic initials AWM. The fact that those letters fail to correspond to any government agency—at any level of government—has long puzzled many New Yorkers. And for good reason: Schwartz made them up. (The proximity of many of these signs to FBI, DEA, and Secret Service offices provides a clue about whose identities he was helping to conceal.)

Which is not to say that he reigned by catering to the mighty. The finest moment of his scrappy civil-service career came when a hundred-odd countries declared war against his towing fleet, which Schwartz had sicced on diplomats who’d collectively dodged tens of millions of dollars of illegal-parking fines under the shield of diplomatic immunity. Like a grade-school miscreant sent to the principal’s office, he was summoned to the United Nations.

“I’m told it was the best session of the General Assembly countries—not an empty seat in the place,” he reminisced as we drove. “The Israelis and Arabs were pouring coffee for each another. Iran and Iraq were unified against me. I felt I had brought peace to the world.” The State Department felt otherwise—especially once other countries retaliated in an outbreak of parking-privilege brinkmanship. It quashed Schwartz’s hometown crusade in favor of global détente.

Even after David Dinkins’ rise to the mayoralty ended Schwartz’s government career in 1990, he continued to fight traffic. Through his consultancy, he advises cities all over the world on transportation strategy. He started a traffic column for the New York Daily News, which he still writes. “William Safire, Thomas Friedman, and E.R. Shipp are all fine as they go, but for my money, the best newspaper columnist in New York is Gridlock Sam,” asserted New York magazine’s Richard Turner in the mid-1990s. “I read it every day, and I don’t even drive.”

“Perusing his column is a way to structure your life, to achieve dominance over the city,” Turner mused. “With the counsel of Gridlock Sam, one can map out the day like Napoleon planning the Russian campaign.”

It’s a telling comparison—as though a driver’s best hope when battling New York traffic was momentary triumph on the way to a catastrophe of empire-crippling proportions. The irony of Schwartz’s nickname, of course, is that gridlock is precisely what he has spent his entire professional life trying to eliminate.

Which brings us to what may be the most prized traffic sign in his personal collection.

At a glance, it doesn’t seem that remarkable: RED ZONE | No Cars 11am-4pm Mon thru Fri. But the zone in question, which he helped to outline in the early 1970s under Mayor John Lindsay, was to have covered some 120 blocks in Midtown Manhattan. The project got far enough along that signs were manufactured, but “just weeks away” from planting them, as Schwartz tells it, “the mayor got cold feet.” (Later, Schwartz worked on another plan Lindsay championed: converting Times Square into a pedestrian plaza. It failed to gain traction amid public opinion typified by a 1977 New York Times editorial that deemed the creation of “a nice pimp and prostitute promenade” a poor trade for subjecting automobiles to “certain chaos.”)

Forty years later, Times Square is perhaps the liveliest and most commercially lucrative pedestrian mall in America. And Sam Schwartz is in the middle of one last bid to reset the way New York moves. It would charge every driver entering Manhattan south of 60th Street, cut tolls on outlying bridges where residents lack strong public-transit options, surcharge the taxis and app-based chauffeurs expected to benefit, and plow a projected $1.5 billion in annual revenues into boosting mass transit services and improving roads and bridges.

It’s called Move NY. To critics, it’s a last-ditch attempt to revive former Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s failed congestion-pricing scheme. To proponents, it’s the first such plan that genuinely has the potential to benefit everyone—and the political sophistication to actually pass. It may be the last best chance for Gridlock Sam to modify the first line of his obituary.

Samuel I. Schwartz was born in 1947, the youngest of four children sardined into a kitchen-and-two-bedroom apartment in Brooklyn’s rough-and-tumble Brownsville section. His parents were Polish immigrants. When Sam was four years old, they moved across the borough to Bensonhurst, where his father ran a small grocery. Insofar as they were trading up, it was for the “orderly violence” of a mob-controlled neighborhood.

“People did not mug old women in Bensonhurst,” as Schwartz puts it. But gangs of kids clashed with chains and zip guns until some of them graduated to the ranks of organized-crime groups that otherwise enforced a fearful peace. It was the sort of neighborhood whose grittiness, to a kid who mastered it, instilled enduring devotion. Sam worked at his father’s store, played stickball on 83rd Street, and worshipped the Brooklyn Dodgers. His oldest brother, Brian, tells a story about the time he and his two younger brothers went to Ebbets Field on “Meet the Dodgers” day in 1956.

“We were able to buy box seats on the railing, right on the field—I think we probably paid $4 a ticket,” he recalls. “And whenever the Dodgers came around, we threw my younger brother over the fence. And the Dodgers would pick him up and put him on their shoulders. So we have these pictures of Sam on Carl Furillo’s shoulders, Roy Campanella’s shoulders, all the famous Dodgers.”

For eight-year-old Sam, it was just in the knick of time. The Dodgers abandoned Brooklyn for Los Angeles the next year, a heartbreak followed by a steady trickle of friends to the suburbs—and then his older siblings. They all moved for the same reason, Schwartz says now: the lure of the automobile, which was simultaneously overwhelming “the streets on which we lived, played, and worked” in “nearly every city that had been built before the advent of the internal combustion engine.”

Sixty years later, Schwartz has the look of a professor who’s happiest during an oversubscribed office hour. There’s more salt than pepper in his gently wavy hair, and a close-cropped beard frames a wide, toothy grin. In conversation he has a way of canting his head and arching one eye, a gesture that suggests bemusement or shrewdness, but derives most closely from simple attentiveness. His oldest brother attributes that trait to the hours Sam spent working for their father, who was particularly sensitive to the needs of his poorest customers. “In that store, not an item had a price,” Brian told me. “And we had to, as kids, look at a customer, look at the item, and then decide upon a price. And you had to begin knowing people very well—like if they were poor, or if they were charlatans. So you really got a very good training in understanding people. And I think Sam really got that in the grocery store. Because you had to really meet with people of different types, of different ages, of different needs.”

That democratic ethos has stuck to Schwartz throughout his adulthood—as has an abiding bitterness over the Dodgers’ abandonment of Ebbets Field.

“It was almost like a death knell for Brooklyn, and for New York City,” he said as we drove. “The Giants moved at the same time. And it began a cascade, post-World War II, in which we saw New York City get worse and worse and worse … And it seemed like that was the pattern, and that would always be the pattern, until someday New York would become uninhabitable by many people.”

But a stubborn hometown loyalty was already baked into him by the time he was a teenager. And Brian, who had become a physicist, pointed him toward what proved to be the ideal target for a city lover with a mathematical bent of mind. “Traffic,” he told Sam during his senior year of college—in a scene both men liken to the iconic “plastics” exchange in The Graduate. So in 1969 the self-described “long-haired hippie” enrolled in Penn’s civil engineering department, where he landed at the feet of a Serbian émigré named Vukan Vuchic.

Vuchic, who retired in 2010 as the UPS Foundation Professor of Transportation Engineering, casts a long shadow over the realm of urban transit. “He’s kind of like the Yoda of the field,” says Paul Steely White, executive director of Transportation Alternatives, a New York advocacy organization. Vuchic still keeps an office in the Towne Building, where he recently reflected on teaching “for 30 or 40 years against the wind” in a discipline that valued the free flow of automobiles above everything else, including the livability of the cities they plied.

“When I was a student in Berkeley, in 1963 or 1964, the annual report of the Traffic Engineering department of Los Angeles came out,” Vuchic recalled. “And it began: ‘Pedestrian remains the main obstacle to the free flow of automobiles in the Los Angeles area.’ That was the attitude. Let’s remove those people!”

Vuchic, who treasures memories of crisscrossing Belgrade in streetcars as a boy, spent his career trying to shift the emphasis to urban quality of life—staking out what you might call the Jane Jacobs approach to transportation engineering. Schwartz proved to be a kindred spirit. “He was enjoying that life,” Vuchic told me, “but not understanding how it can be made. So I think my teaching gave him the basis.”

Vuchic also infected Schwartz with a certain radicalism about the field.

“Traffic engineers have failed,” Schwartz once told Aaron Naparstek, the founding editor of Streetsblog, a transportation-focused website in New York. “If you compare the accomplishments of our profession [in this country] over the last 50 years to the medical profession, our performance is equivalent to millions of people still dying of polio, influenza, and other minor bacterial diseases that have been cured.”

“It’s totally Sam that he can be so irreverent and honest about his own profession—and really challenge himself and the profession to do better,” White says, offering a full-throated defense of what struck me as a questionable comparison between traffic planning and the biomedical revolution.

“More than 40,000 people are killed on our roadways every year,” White says. “You know, 80 percent of our public space are streets, and traffic engineers have designed and managed that space for one purpose, for decades. And that purpose of course has been to move cars, as quickly as possible. And if there’s congestion, we build our way out. That approach has really had severe negative impacts—including even the obesity epidemic. And Sam, being honest about that, and not denying it, and instead trying to reform it—he’s recognizing the impact that traffic engineers have, and their responsibility.”

Fresh out of Penn, Schwartz wanted to work for the New York City Transit Authority. That hope crashed against a tough job market ruled by rank-and-file employees moving up the ladder. So, master’s degree in hand, he took what he could get: shifts driving a taxi cab. When he eventually accepted a job as a junior engineer in the city’s traffic department, he felt “a little bit like I sold out,” as he put it years later in a letter to Vuchic. “I was in ‘car-land.’”

He didn’t have to wait long to get a powerful lesson in “the practical consequences of overdependence on cars.” On December 15, 1973, a dump truck carrying 30 tons of asphalt for highway repairs dropped through the West Side Elevated Highway onto the street below. A sedan tumbled down after it—though miraculously no one was seriously injured.

The elevated highway’s subsequent closure south of 18th Street gave Schwartz a tall task: figuring out what to do with the 80,000 cars a day that would need an alternate route. It was a formative experience, because something strange happened: the traffic simply seemed to vanish. “Somehow, those eighty thousand cars went somewhere, but to this day we have no idea where,” Schwartz writes. “Or how, two years later, twenty-five thousand more people were getting into Manhattan’s Central Business District.”

It was a demonstration of what economists call induced demand—that an increase in the supply of a good, in this case a road, stokes higher consumption of it. Shrink the supply, and to some degree traffic would disappear with it. The effect was compelling enough that the West Side Elevated Highway was ultimately taken down rather than rebuilt, saving the city a considerable bill for construction and maintenance at apparently negligible costs to drivers.

For the next few years, Schwartz toiled in the middle ranks to advance an urbanist and environmental agenda that frequently clashed with departmental and mayoral priorities.

In the mid-1970s, the National Resources Defense Council sued New York for failing to implement a transportation plan, filed under the Clean Air Act, that mandated tolls on the East River Bridges to improve air quality. Mayor Abraham Beame and New York Governor Hugh Carey fought the NRDC in federal court. Meanwhile Schwartz covertly fed a young NRDC lawyer named Steve Jurow information that undercut the city’s official predictions of traffic Armageddon. (The city also argued that the tolls would cause excessive economic harm.)

It was a monumental battle. As Jurow remembers it, the US district judge who presided over much of the case, Kevin Duffy, “would hold his head and moan whenever we came in.” It went all the way to the US Supreme Court, where Justice Thurgood Marshall ordered the plan to be implemented.

“Only an act of Congress could stop it,” as Schwartz wryly puts it, “but, unfortunately, that’s just what happened.” The city’s Congressional delegation got a law passed permitting the city to substitute other pollution-reducing strategies for the tolls. In the end, Schwartz—still working hand-in-glove with the NRDC—managed to win parking restrictions as well as Manhattan’s first truly exclusive bus lane on Madison Avenue. It was small-ball compared to the original vision. But in Jurow’s estimation, “It ended up pivoting New York City transportation policy toward transit” in a meaningful way.

Ed Koch’s election as mayor catapulted Schwartz up the ranks. By 1982 he was the traffic commissioner—which put him in charge of the least-loved army in New York.

“Brownies are the most abused, assaulted, kicked, spat upon, cursed, threatened, and run over of civil servants,” New York magazine asserted about the city’s traffic-control agents in a 1984 article about the sudden doubling of their ranks. “Yet, last month, when a bill was proposed in the City Council that recommended making it a felony to attack a traffic-control agent, Councilman Rafael Castaneira Colon, a Bronx Democrat, opposed the measure. ‘If they’re getting beaten up out there,’ Colon reportedly said, ‘it’s because they deserve it.’”

A bureaucrat with his eyes on a bigger prize might have commanded such a force from the remotest corner office he could find. But for Schwartz, the traffic generalship was the prize. He relished hitting the streets with his platoons, prodding idling drivers through a megaphone.

Stories of his exploits have attained almost mythical status, like the time he ticketed Mayor Koch’s car for illegal parking while the two men were having lunch together. (Thirty-odd years later, Schwartz maintains that it was a mix-up; his agents were just overzealous when he was in the vicinity.) But he gleefully claims responsibility for personally ordering a Channel 7 news truck to be towed—while its reporter was interviewing him.

“It was Milton Lewis,” Schwartz reminisced as we drove, forcing his voice through his nose in a caricature of the late newscaster’s brash questioning. “He said, ‘You would tow other city cars?’ And I said, ‘Yeah.’ He said, ‘You would tow diplomats?’ And I said, ‘Yeah!’—I said, ‘I’d even tow the press.’ And he said, “You would tow an Eyewitness News vehicle?!” And I said, ‘You’re in the no-standing zone!” Whereupon Schwartz signaled for a tow truck to drop its hook. “And you saw the tow truck pick up the Eyewitness News vehicle,” he chuckled, “with the crew filming it kind of going off into the sunset. It was a great story for Milton Lewis, and I made my point.”

Illegal parking did indeed plummet under Schwartz’s iron fist, and traffic speeds crept up—from 7.9 to 9.5 miles per hour on the avenues—according to that New York article. His star rose further when, in 1986, the Department of Transportation was riven by an extortion and bribery scandal of such dramatic scope that it later inspired the pilot episode of Law & Order. As head of the only bureau to emerge untarnished, Schwartz was appointed acting commissioner, then first deputy commissioner, of the entire DOT.

It’s hard to estimate a single bureaucrat’s impact on a massive department, particularly in a city as big and complex as New York. Since the Robert Moses era, the city’s most consequential DOT commissioner has probably been Janette Sadik-Khan. During her six-year tenure under Mayor Michael Bloomberg, Sadik-Khan threaded New York with nearly 400 miles of bike lanes and created 60 pedestrian plazas, including the one at Times Square.

“If Gridlock Sam didn’t exist, it would be necessary to invent him,” she told me in January, calling him a “New York institution” and a mentor.

“I’ve always considered him my brother in infrastructure. He battled these corrosive forces of decay and, also—and just as importantly—public indifference.” The bike lanes and plazas that were her proudest achievements, she said, stoked and depended on a “culture shift that really accepts people and bikes as critical parts of the transportation network.

“But just as vital,” she added, “though much less noticed by the media or the public, are the nuts and bolts of managing the 789 bridges in New York, the 6,000 miles of asphalt, the 12,000 signalized intersections. And so I’m forever indebted to Sam for seeing farther than the city’s next fiscal year. And for his strength to stand firm against political winds.”

One measure of Schwartz’s legacy is the subtle but significant change in how the department, under his leadership, conceived of its responsibilities. Traffic engineering had been (and to a considerable extent still is) fixated on two considerations: speed and safety. Schwartz worked to expand that focus to encompass a wider set of considerations.

Sadik-Khan pointed to the case of the Williamsburg Bridge as an emblematic example. The 1988 discovery of ruptured structural steel in the 84-year-old span—the same problem that caused the West Side Highway collapse—forced Schwartz to completely close it to all traffic (a first for a major city bridge). The damage was widespread, and New York would need federal money to address it. Only the feds wouldn’t pay to repair what they deemed a “substandard” bridge. Which biased the process toward demolishing and replacing it with a modern span: wider lanes, ample shoulders, and lengthier approach ramps to expand the capacity beyond the quarter-million daily crossings it was already hosting.

“The Williamsburg Bridge debate revealed a fundamental truth about transportation,” Schwartz writes in Street Smart. “[T]he cost-benefit equations of traffic engineering, in which benefit number one was getting more drivers to their destinations more quickly, weren’t based on impartial and unbiased math. They were a set of blinders that left only a very narrow set of options visible at all.

“We could rebuild a bridge for $700 million, and leave the city with an ongoing maintenance bill of at least $20 million annually for the next 30 years in order to put more cars on the streets of the country’s most crowded city … This was another sensible infrastructure investment that wasn’t sensible at all.”

A second factor pushed the calculus even further toward building a high-capacity modern bridge: standard 12-foot-wide lanes would be safer than the Williamsburg Bridge’s 9-foot-wide ones. That was an all but universally accepted truth among traffic engineers. Except, when Schwartz mapped three years’ worth of accidents on the bridge, the data showed something counterintuitive: the bridge’s safest sections were where the lanes shrank to their narrowest points, near the support towers. Perhaps because they caused drivers to behave more cautiously, “grossly substandard lanes seemed to be the safest of all.”

That argument carried the day. The bridge underwent a 15-year rehabilitation. But for Schwartz, the victory’s significance lay partly in its impact (or, rather, lack thereof) on the neighborhoods on either side of the span. The long approach ramps required for a modern bridge would have come at the expense of significant acreage in Williamsburg and the Lower East Side. To some proponents, that was a plus: a chance to condemn blighted property. Yet today, Williamsburg is one of the most vibrant (and expensive) neighborhoods in Brooklyn. And the gentrifying Lower East Side is one of the most ethnically and socioeconomically diverse areas in Manhattan.

“He pushed back against this accepted wisdom that the city should just tear the whole thing down and start again,” Sadik-Khan told me, “which would have leveled much of Williamsburg and the Lower East Side in the process—and would have probably stopped the revival of those neighborhoods before it even started.”

Traffic engineering during America’s highway-building heyday may have sapped vitality from our cities. But done right, Schwartz suggests, it can be a tool for urban preservation.

The Williamsburg Bridge now carries about 115,000 vehicles every day. Schwartz wants to charge all of them $5.54 each way. The same would go for the other East River bridges, which have heretofore been free to motorists (though not to subway passengers). That charge would equalize the cost of crossing those bridges with the current tolls for the Metro Transit Authority tunnels into southern Manhattan.

In contrast to the Bloomberg administration’s failed congestion-pricing plan, tolls on the MTA’s major outlying bridges (like the Throgs Neck, which links Queens to the Bronx, for example) would be decreased by $2.50, or 45 percent. Schwartz’s Move NY plan also calls for using some of the projected $1.5 billion in new revenue to subsidize fares in “transit deserts”—discounting the cost of commuter rail and express buses.

Overall, it projects investing $375 million a year in road improvements, and $1.15 billion a year in mass transit. (The subway system’s antiquation—which runs from cloth-covered wire, to hand-operated interlocking machines, to electromechanical relays so old that rail manufacturers have long stopped making replacement parts—greatly restricts the number of trains it can operate, and probably inflates the cost of operating them.) Significantly, those numbers happen to be just enough to plug a Statue-of-Liberty-sized funding gap in the MTA’s current five-year capital plan, which still remains unsettled in its second year.

Move NY is by no means the first or only plan of its kind. But it has attracted an uncommonly wide range of supporters.

That they include Charles Komanoff testifies to its technical merits. Komanoff, a transportation economist and environmental activist, was profiled by Wired magazine in 2010 as “The Man Who Could Unsnarl Manhattan Traffic.” He has developed a monumental, 67-page Excel spreadsheet, called the Balanced Transportation Analyzer, that breaks down “every aspect of New York City transportation—subway revenues, traffic jams, noise pollution—in an attempt to discover which mix of tolls and surcharges would create the greatest benefit for the largest number of people.”

“Sam and I were working on parallel tracks,” he told me in January. “And around 2011 or 2012, I had to admit—and I’m choosing my words deliberately, because I kind of didn’t want to—but I had to admit that key elements in Sam’s vision were politically superior, and also superior from a traffic-management standpoint, to what I had been proposing.”

Schwartz’s plan was “pure genius,” Komanoff then gushed, letting his traffic-geek flag fly—“a thing of Platonic beauty as well as political and logistical appropriateness.” Now Komanoff is a vocal leader in the Move NY coaliton.

Tom Wright is president of the Regional Plan Association, an urban transportation and economic-development advocacy organization that focuses on the greater New York metropolitan area. He stresses that the idea of tolling the East River bridges wasn’t new even when RPA pushed for it as far back as 1996.

“What Sam did with Move NY was change the entire political dialogue,” he told me, “by saying that the crazy thing is that we’re charging motorists who don’t have transit options a fortune, and we’re not charging motorists who do have transit options. So, by widening the scope—and making it not just about the East River, or just the Harlem River, or Manhattan to Brooklyn—by encompassing a whole conversation about the Throg’s Neck bridge and the Verrazano Narrows bridge, and things like that—he put regional coordination on the radar. And he does it in a kind of commonsensical way.”

“Sam is one of most influential planners of his generation, and an inspiration,” added Wright, who is a planner of some renown in his own right.

As we drove around, Schwartz credited Move NY’s political merits to the fact that he’d been able to shape it as an independent actor.

“I did not want to leave city government,” he confessed. “I would have died with my boots on, had it not been for another mayor who came in and didn’t reappoint me.” But his second career as a private consultant, advising cities on transportation policy, has its advantages.

“When you’re in an administration, ultimately you’re all speaking for the mayor, or on behalf of the city, or governor,” he observed. “And once a mayor endorses a plan, there’s far less room for negotiations. There’s far less room for change, because people have to go back up to the mayor to make the change. And so the plan is what the plan is, and then you go forward and try to push that plan.

“This plan doesn’t have to be set,” he added. “So it’s evolved over time. It’s not exactly the same plan that I had first presented. Some of the projects I’ve removed, because of trying to gain consensus with a lot of people. I don’t have a client here … So it makes life much easier. I’m doing it as a private citizen.”

The upside of this approach is perhaps most apparent in the Automobile Club of New York’s position on the plan. When, in 1980, Schwartz’s department proposed banning single-occupant cars from the East River bridges during the morning rush, the AAA affiliate successfully sued to stop it. It also opposed Bloomberg’s congestion-pricing plan. But it has cautiously supported Move NY—as has the New York Motor Truck Association, another past foe of congestion pricing. Schwartz says he also has about 50 state legislators lined up behind the plan, which would require state-level approval.

What’s eluded him, so far, is the most important player in a game that will ultimately be decided in Albany: New York Governor Andrew Cuomo. At the outset of 2016, Cuomo unveiled a transportation-infrastructure capital plan that he billed as the largest in the state’s history. But on balance the emphasis falls on the upper portion of the state—where toll reductions on the New York Thruway were a political selling point. And Cuomo’s pledge to contribute some $8.3 billion in state money to the MTA’s capital plan rests on unspecified funding mechanisms. Transit advocates fear that it will rely on debt, that subway straphangers will ultimately bear the burden via higher fares, and that Manhattan’s mounting traffic congestion will inch closer to gridlock.

In a mix of worried and wishful thinking, Komanoff believes that this year will be a fateful one for Move NY. “By June 30, either we won or game over. That’s when the legislative session ends,” he told me. The indebted MTA will have to adopt a five-year capital plan, he thinks, and Move NY represents the most realistic way to right its finances. “This is kind of the last year that our plan has a real chance.” The longer it sits without gaining traction, he fears, the more it will begin to seem like yesterday’s scheme—and the more likely politicians will be to wait for tomorrow’s next big thing, be it real-time GPS-based metering or self-driving cars.

Wright is at once more pessimistic and more optimistic. “I think the window on [the MTA’s five-year capital] plan has closed,” he told me. “But in two or three years, we’ll have to start talking about the next capital plan.” Congestion pricing “will happen some day,” he said. “And I think that when it does happen, it will be a lot closer to Sam’s iteration” than anything else that’s been proposed. Sadik-Khan agrees, saying that “it’s a matter of when , not if.”

Meanwhile, Gridlock Sam soaks up a city life that has in many respects gotten better since his first 50 years of stubborn loyalty to it. And he takes pleasure in the thought that he helped push the pendulum that has lately begun to swing so far in his direction. Momentum can take a long time to shift in New York. But when it does, it can be a powerful force.

Most weekends, Schwartz plies one of the few parts of Manhattan that stands apart from the grid. The Hudson River Greenway bike path has an access point a stone’s throw from his Riverside Drive apartment. The route hugs the tidal estuary’s bank nearly the entire length of Manhattan.

“I ride it just about every week,” he said with satisfaction as we returned to the Upper West Side at the end of our day. “I go up to the George Washington Bridge. I chill out at the Little Red Lighthouse and just sit and look at the river, which flows both ways.”

I met Sam during my time as a member of Manhattan Community Board 8. I was active on transportation and related issues, and got to work with him on a number of occasions. As I recall, early on he was still TC, later during his early consulting years. He was always quite the professional, and a pleasure to deal with.

Sam encouraged me to attend an infrastructure conference at the Cooper Union, during which the then head of the Port Authority announced to those present that there was no point in building a train to the plane (mass transit access to our local airports) because no one would use it. Well, this clown (my apologies to clowns) had his limo, unlike the rest of us. But when PA finally built a train to JFK years later, it did it the worst possible and most expensive way, perhaps to try to prove the guy right by doing a horrible job. At the time though, I think the room was in collective shock.

Sam sticks to his instincts and wisdom years later, and he is still a valuable resource to New York City and the country!