A Penn Engineering creation flips the robot narrative.

When it comes to Hollywood, robots are often cast as the perfect villains, destined to wreak havoc, turn on their creators, or show up programmed to kill humans. Those depictions are exactly what flashed through Abriana Stewart-Height Gr’24’s mind when a film director came to campus in 2019, asking to use a robot from Penn Engineering’s Kod*lab in his new indie film.

“I don’t want people to be afraid of robots, because there’s so much they can do out in the world to help benefit society,” Stewart-Height says. “I was very nervous about whether this movie would give the robot a negative image and make it the bad guy—and I said straight up that if that was the case, I would not help with the movie.”

But nearly two years later, you can find little X-RHex (pronounced “ex-rex”), a robot from Penn, in the new sci-fi film Lapsis, released on February 25. Bug-like and unthreatening, about the size of a small dog, it high-steps through the forest alongside human actors, unspooling cable wire with a merry mechanical whir.

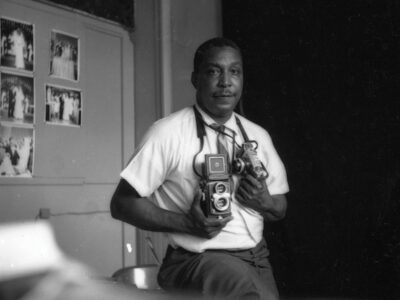

What you won’t see on screen is the trio of Penn Engineering doctoral students standing nearby: Stewart-Height using a wireless gaming controller to direct X-RHex’s every move; Wei-Hsi Chen Gr’22 wielding a laptop linked to X-RHex’s internal computer; and J. Diego Caporale Gr’22 ready to spring out and grab the robot if one of its six legs snaps (again) or rain starts plopping down on the delicate electronics.

“The X-RHex was the star, truly,” says Noah Hutton, writer and director of Lapsis, “but the students were like the supporting cast.”

Set in a parallel present, the film centers on Ray, a guy from Queens who lands a job tramping through the forest, laying out miles and miles of cable to link enormous metal cubes. The tougher the routes he and his fellow gig workers select, the better their payouts.

While first introduced in a training video as “little helpers” useful for “picking up the slack when routes can’t be completed, and always pushing cablers to set new personal bests,” it turns out that the robots (played by Penn’s X-RHex) can easily out-cable the human cablers, costing them their paydays. The result is a battle between man and machine—but driven by an evil corporation, not evil robots.

Hutton had already written the script when he began searching for the perfect robot to play his film’s automated cabling carts. “I wanted something that had this cute factor, while characters might also feel uneasy about what [the robots] were doing within the world of the film,” Hutton says. “I saw the YouTube video of [X-RHex] walking around, and I thought, this would be perfect for a forest cabling robot.”

After a few conversations with Daniel E. Koditschek, the Alfred Fitler Moore Professor of Electrical and Systems Engineering and namesake of the Kod*lab, Hutton and some of his production crew arrived at Penn to meet both X-RHex and the people who power him.

“Once they told me more about the plot and I realized that the robot wasn’t the villain in the movie, I thought it was a great opportunity to show robots in a different light and educate people in the movie-making business—because at the time we met, they didn’t know much more about robots than most other people,” Stewart-Height says.

For a handful of days in the summer of 2019, X-RHex and a cadre of Kod*labbers traveled to upstate New York to set up movie robot headquarters: a cabin in the woods filled with batteries, chargers, cables, motors and replacement legs. “People assume the robot is always going to be strong and robust,” Chen says. “In reality, it needs to be treated more like a baby.”

Like Stewart-Height, Chen began working with X-RHex shortly after he arrived at Penn. It’s a good entry-level robot for students, he says—“easy enough for beginners to pick it up and try to write their own code and just test it out.”

The original RHex debuted in 2001—the fruits of a joint project between teams at McGill University and the University of Michigan, where Koditschek was based at the time. It was among the first legged robots that didn’t need to be plugged into a wall outlet, and thus one of the first capable of navigating the outdoors.

Nine years later, with RHex starting to show its age and Koditschek at Penn, a group of Penn graduate students decided to update the robot. They named the revamp X-RHex, “and we’ve been beating it up for a decade now,” Koditschek says.

RHex falls into the subgenre of bio-inspired robots. In this case, the inspiration was a cockroach, with six individually powered legs. It’s petite enough to fit in a backpack, has the computational power of up to two computers, and its flat back can serve as a carrying surface, table or mini lab bench. “It’s like a research lab on legs,” Stewart-Height says, “where you can have everything you need to collect samples and analyze them on the robot itself.”

In the last few years, X-RHexes have gone out on multiple desert and forest research missions. But Stewart-Height says they may be most useful for search-and-rescue work, helping to find people after disasters. Compared to human or canine searchers, robots can be faster, fatigue-proof, and “if something falls on them and they break, it’s sad, but it’s a robot, and we’ll build another one,” she says.

Right now Stewart-Height is using the X-RHex to investigate what happens when a hexapodic robot snaps one of its legs: rather than needing an instant repair, can the robot learn to identify which leg it has snapped and adjust its gait accordingly? For inspiration, she’s turning back to biology, since an injured animal or human intuitively adjusts their movements if they break or lose a limb.

Of course, you won’t see any of that in Lapsis. But you will see a new representation of work-buddy bots that raises broader questions, including for actual roboticists. “Noah’s movie made us think about the ethics in robotics,” Chen says. “We know a robot can only be as good as the operator is going to be. But what about the creator? Does the creator have a responsibility in making the robot as hard to use for bad as possible? It strikes a lot of conversation, and I won’t say we have the answers.”

To Koditschek, Hutton’s film is “a triumph from people who are interested in explaining and popularizing science and technology in an honest way.”

“We’re good at designing new robots and thinking about how to animate them and make them do tricks,” Koditschek adds. “We’re not always as good about thinking through the implications of their impact on society. We’re grateful to have had this opportunity to connect up with society in a much more comprehensive way than we can ever do with our papers.”

—Molly Petrilla C’06