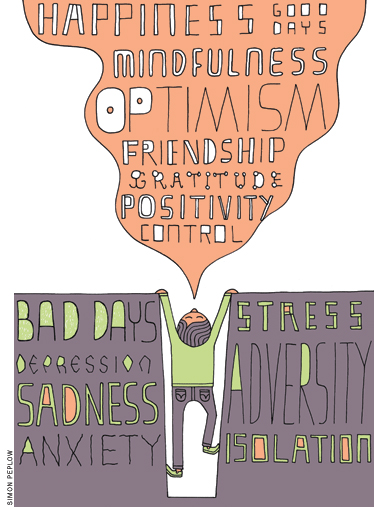

Class of ’91 and ’06 | Not long ago, an optimist and a pessimist launched a business and a website. Their goal: More happiness.

“We are really focused on our mission: To inspire people to be happier and more resilient,” says the self-described pessimist, Doug Hensch C’91. “If we can continue to do that, the business will take care of itself.”

“We’re not a bunch of bouncing-off-the-walls happy people,” adds Andrew Rosenthal C’06, optimist. “We’re building a solution that’s relevant to real-world people.”

Hensch (president and COO) and Rosenthal (vice president for business development and marketing) are the co-founders of Happier.com, whose goal is to serve as a “personal trainer for your happiness.” As personal trainers go, this one is pretty affordable, not to mention user-friendly.

Rosenthal is also project manager at Penn’s Positive Psychology Center, which happens to be headed by Martin E.P. Seligman Gr’67, the Zellerbach Family Professor of Psychology and godfather of positive psychology. Hensch segued into the positive-psychology field half a dozen years ago when, as a senior manager at Nextel, he developed a workshop for a team of finance executives around the topic of using their strengths to be more productive. (After seeing some members of that very cynical group go from “severe dysfunction” to tearful encomiums, he recalls, “I knew that I had to learn more and work this body of science into my career.”)

The company they founded and the website that delivers the goods represent the interface of positive-psychology research and IT commerce. That’s no accident.

According to Rosenthal, Seligman introduced him to a group of investors on Philadelphia’s Main Line who were interested in the business of positive psychology, whereupon he presented “this idea to go after consumers who were really interested in self-improvement through positive psychology.” The investors then put up “enough funds to get started.”

Seligman, who describes Rosenthal and Hensch as “two of my most talented young colleagues,” notes that they formed the company to “provide tests and exercises in positive psychology to the general public.” He adds: “I hope this will be a way to amplify the dissemination of these useful instruments to the world.”

After surveying the field and laying the groundwork, they formally launched the website this past September.

“We knew that the primary consumer interest was something that was affordable, that didn’t require a master’s degree or 10 weeks of training, and could be done in the privacy of one’s own home,” says Rosenthal, who serves as president of the Penn Alumni Club of Philadelphia in his spare time. “That’s where the Web solution came from. From the very beginning, Doug and I always asked, ‘What can we do online?’”

By late November, the website, which provides a range of online tools, exercises, questionnaires, and the like, had attracted some 50,000 users, a modest portion of whom were paying a monthly fee of $5 to $10 for premium content.

“We’ve seen very rapid growth,” says Rosenthal. “It’s also a much broader audience than we thought, so we’re really excited.” Happier.com has a substantial following on Twitter and Facebook, and Rosenthal even talks about apps for smart-phone-users. But the website itself, whose graphics are simple to the point of simplistic, is very easy to navigate.

“All of Happier.com is built to be very low-tech,” Rosenthal says. “We’re very proud of what we’ve done, but we’ve been very careful to make it easy and accessible. I want my mom to be able to use it.”

The goals range from “Decrease your symptoms of stress, anxiety, & depression” to “Increase your resilience” to “Build positive relationships.” Tools include “happiness plans,” exercises, and tests. If you pick “Decrease your symptoms of stress, anxiety, & depression,” it offers recommended activities (starting with the Optimism Test, which presents 12 different real-life situations to respond to, and Three Good Things, which is essentially an exercise in finding positive things that happen each day, as well as answering “Why did this good thing happen?”). You can then enter the events and their causes in the My Journal section, rating and examining them over time. The Science section discusses—in brief, bulleted entries—the gradual nature of the benefits, the results for those who have done this exercise compared with a placebo group, and how it works. Finally, there is a directory that offers a wide range of positive-psychology coaches, therapists, trainers, educators, and consultants.

Videos by Seligman (who’s listed as a consultant) and other experts in the field testify to the science-based nature of the enterprise.

“We knew that there are experts in this subject area, so Doug and I said, ‘Let’s build a solution, and let’s turn to these experts for the content,’” says Rosenthal. “We work with our experts to figure out where the science is going and what to build next.”

Click increase my resilience, for example, and you’ll call up a video of Seligman talking about why some people bounce back from a setback quicker than others. The resilient person “thinks about the setback differently from the non-resilient person,” he explains. “The resilient person says, ‘I can change it. It’s just this one situation; it’s going away quickly.’ The non-resilient person—the person who doesn’t bounce back—says, ‘It’s going to last forever; it’s going to undermine everything I do.’” Standard-issue Seligman, grounded in decades of research.

Hensch, who says he could have used those positive-psychology techniques and tools while he was quarterbacking Penn’s varsity football team in the early 1990s, describes himself as a “heavy user” of Happier.com and the tenets of positive psychology in general.

“When something bad happens, my pessimism kicks in immediately,” he says. “I usually go to the worst place—‘It’s my fault.’ ‘I stink.” ‘There’s no way out of this.’ Positive psychology has helped me implement some very basic tools into my life that help me challenge my own thinking. I listen to myself now, and I have learned to argue with these destructive thought patterns.

“I’d like to think that I’m the perfect person to be running a ‘happiness’ company, in that I’m also the perfect consumer for these tools,” he adds. “It’s a lot easier for me to tell a room full of HR people that this stuff works when I have the personal experiences and results to back it up.” Since pessimists “tend to take critical views of a situation and are more likely to identify risks,” he points out, “my pessimism helps me run the business and keep things in perspective.”

“My understanding of the research is that about 50 percent of an average person’s happiness is set at birth,” says Rosenthal. “And about 15 percent of happiness can be attributed to outside things like marriage, or weather, or salary, or things like that—external factors. So that remaining 35 percent, as far as we can tell, is changeable. From a scientific perspective, that’s where we’re coming from—to give people the tools to work on changing that 35 percent. It’s very realistic to say you can’t change everything, but here’s what you can change and here’s how.”

Given the number of touchy-feely apostles of cheer who populate the pop-psych world, it’s worth emphasizing the point that Seligman makes in a Happier.com video: “Positive psychology takes tests and interventions and studies them rigorously and scientifically, asking which ones are just boosterism, and which ones actually work. So positive psychology is a science. It’s not an armchair philosophical endeavor.”

Of course, not everyone takes the time to make such distinctions, as is clear from Barbara Ehrenreich’s acerbic Bright-Sided: How the Relentless Promotion of Positive Thinking Has Undermined America.

“It’s good news to me that there are critics out there, because it helps to show that this is becoming more mainstream,” says Rosenthal, though it’s fair to say that he hasn’t been impressed by the criticism. Besides, the notion that everyone should be happy all the time “is not realistic, it’s not scientific, and it’s not fair,” he adds. “We don’t believe that. We believe that people generally want to be happier, and that there are tools out there that work, and that we should tell them and help them learn what works for them.”

Given that “negative emotions play a great role in life,” he adds, “the reality is that a lot of this stuff is hard work—it’s not easy. People turn to Happier.com looking for a happy pill—that’s not realistic or scientific. But some of the best feedback we’ve gotten is from users who got their act together—they’re successful, but they approach things from a pessimistic point of view, which has been helpful but also a hindrance in life. They say, ‘You know, through deliberate practice, and from watching the videos and working through the tools on Happier.com, I’ve been able to notice a shift in my negativity.’”

“With proper funding, Happier.com will be the brand name in self improvement,” says Hensch. “Right now, we’re focused on improving the tools, optimizing our marketing programs, and continuing the revenue growth through subscriptions. And now that we have shown that there is a real, pent-up demand for this, we’re talking to potential investors to take this to the next level.

“We’re helping people every day, and that means a great deal to me,” he adds. “It’s just icing on the cake that we are building a profitable business.”

—S.H.