Samba Sessão, the exhibition of Afro-Brazilian art and film that opened last month at the Arthur Ross Gallery and runs through July 29, isn’t really about samba per se. But on a metaphorical level, the title works just fine.

The samba is a “quintessentially Brazilian art form,” notes Tamara Walker, assistant professor of history at Penn and co-curator of the exhibition. “We see the idea of a samba session as being both an invitation to share in and better understand a popular experience, as well as a lure into a lesson on things about Brazil that don’t get as much attention as samba but are valuable touchstones nonetheless.”

Referring to another kind of Brazilian music and dance, she adds: “In other words, come for the samba, stay for the frevo.”

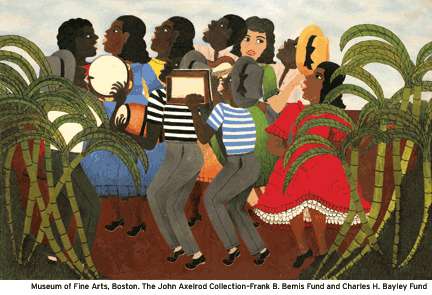

Whatever the rhythm, Samba Sessão pulses with life. In the paintings, sculptures, and films that comprise the exhibition, “we witness birth, death, love, conflict, belief, and fantasy,” says co-curator Gwendolyn Dubois Shaw, as well as “bustling life in the big city and the slower pace of country roads—side-by-side with ribald dancing and visionary rituals.”

Brazil has also been a fertile land for cinema, and video reviews of Brazilian films—made by Penn students from the Halpern-Rogath Curatorial Seminar Program—can be viewed on computer screens set up beside the paintings and sculptures. For Shaw, an associate professor of American art at Penn, “the real power of the exhibition lies in the combination of works of popular Brazilian art and the student-produced videos.” The films they reviewed range from Bye Bye Brazil to Kiss of the Spider Woman to Orfeu Negro.

In some ways, Samba Sessão originated “almost 10 years ago,” Shaw explains. Back then she was an assistant professor at Harvard and an overseer at the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) in Boston. One of her MFA colleagues was John Axelrod, a prominent collector of African American and Latin American art whose collections included the pieces in Samba Sessão. Axelrod encouraged her to work on the Afro-Brazilian art, and kept doing so even after she came to Penn.

When she met Walker, “we began to talk about shared interests,” recalls Shaw, and they soon concluded that they should collaborate on the Afro-Brazilian project that Axelrod had been suggesting. The first product of that collaboration was a course sponsored by the Halpern-Rogath Curatorial Seminar Program, which not only enabled them to mount an exhibition but also to take the students to the source of the art—Brazil.

“Six of the eight students [in the seminar] made the trip,” says Shaw. “It was phenomenal—absolutely amazing. We visited about a dozen museums in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, and also visited with art dealers and collectors, purchased books, and got to experience a little bit of Brazilian daily life. We traveled between the two cities in a van, so we also got to see the countryside and the exurbs and farmland, and a little bit of the mountainous, hilly areas. It was eye-opening.”

Despite the subtitle, “not all the works are by Brazilians of African descent,” Shaw adds. But they do “emphasize the pervasive influence of African and Afro-Brazilian culture on the country as a whole.” In a sense, “for us to say Afro-Brazilian is really just to say Brazilian.”

Brazil was one of the last countries in the world to abolish slavery, and most of the artists in Samba Sessão were born shortly after the abolition of slavery in 1888, notes Walker. “There is a clear shadow that looms in the conceptual background of their work. But so [does] the rich cultural tapestry that Indians, Africans, and Europeans created in Brazil. In many ways the works represent a balancing act between the dark and the light, between the somber and the celebratory, and between trauma and triumph.”

Each object in the exhibition “tells a story that in some way calls to mind Brazil’s history of slavery, race-mixture, migration/immigration, regional differentiation, patriarchal family organization, et cetera,” Walker adds. She cites the work of Agnaldo Manoel dos Santos and Rubem Valentim, noting that “both artists make use of the syncretic religious symbols that African slaves in Brazil created in an effort to preserve their own faith in the face of forced conversion to Catholicism.

“That said, we don’t want to over-determine how our audience will experience the show and the pieces,” she adds. “Part of the fun will be in the discovery! We only ask that the audience be willing to experience the objects as products of a region with its own history. More than anything we want the exhibition to be the beginning of a journey towards learning more about Brazil.”

—S.H.