Paul Hendrickson’s fresh take on Frank Lloyd Wright.

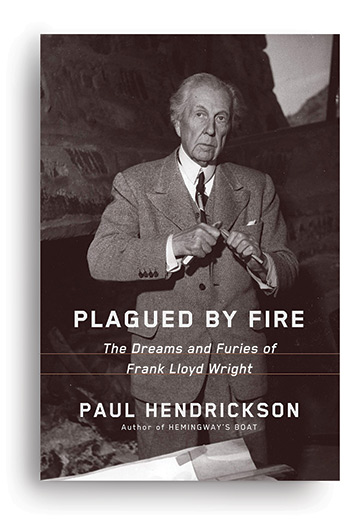

Plagued by Fire:

The Dreams and Furies of Frank Lloyd Wright

By Paul Hendrickson, faculty

Knopf, 2019, $35

By JoAnn Greco

Paul Hendrickson is, as he makes clear in his new book, Plagued by Fire: The Dreams and Furies of Frank Lloyd Wright, a man on a mission. He has theories to prove, deceptions and misconceptions to debunk, and mysteries to unravel. In his engrossing biography of the celebrated architect, Hendrickson—a senior lecturer in the English department whose previous books (including a biography of Ernest Hemingway) have received awards from the National Book Critics Circle and National Book Foundation—calls on skills he honed during a 24-year career reporting for the Washington Post. The author spent seven years traversing the country, visiting Wright sites; tracing the architect’s footsteps in Chicago, Madison, and elsewhere; interviewing associates and relatives; and poring over news clips and correspondence.

When he writes, “to study old timetables is to get an appreciation for the crawling agony of that evening,” referring to a trip the architect took on the Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul Railway, you know darn well that Hendrickson studied those schedules, counted the number of stops along the route, and diligently calculated the minutes and miles between each one. But when he fancifully likens the 87-year-old Wright, dressed in a white suit and shoes, to “an ice cream man trying to enter heaven,” he draws on his more recent career teaching creative nonfiction, indulging in occasionally showy language while attempting to “dream myself into the moment.” More often than not he’s successful: in a six-page tour of Wright’s debut Usonian home from 1936—the more modest successor style to his richly appointed and sprawling Prairie houses—his thousand words are worth so much more than the single accompanying photo. What else to expect from a man who has taught a class called “Writing from Photographs”?

Hendrickson’s maddeningly ornery, determinedly cagey, astonishingly prolific subject merits the dogged investigation, the out-there musings, the florid writing—and this author is certainly not the first to take up the challenge. New Yorker writer Brendan Gill, biographer Meryle Secrest, and New York Times architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable have produced hefty “life of” tomes, and several of Wright’s relatives and students have written memoirs. Wright also served as inspiration for Ayn Rand’s novel-cum-manifesto The Fountainhead; a Ken Burns documentary; and an opera (Daron Hagen’s Shining Brow).

Wright might well qualify as the world’s first “starchitect,” cloaking himself early on in a persona that revolved around a devil-may-care attitude, a tendency toward imperial pronouncements, and a fierce individualism. His stature as an icon, though, comes foremost from the 500 or so built projects (eight of which were recently added to the UNESCO World Heritage List) that are his enduring legacy. In some of his book’s loveliest passages, Hendrickson writes expertly and appreciatively on Wright’s innovations and talents.

Still, there’s no doubt that Wright’s outsized personality is also part of his mystique. When once asked to identify himself in court, he declared that he was the world’s “greatest architect,” adding for good measure that his immodesty was compelled by the fact that he was under oath. Although Hendrickson provides plenty of examples of that strong ego, one of his stated goals is to prove that behind the hubris there was humanity. Digging deeper into oft-told tales from Wright’s personal narrative—the three wives, seven children, and assorted scandals, financial troubles, and comebacks—the author teases forth the often tortured, often insecure man who hid behind the architect’s “many masks” (to borrow the title of Gill’s biography).

Hendrickson also contributes a fresh perspective by taking a group biography approach, spotlighting figures who have been at best sketchily drawn and at worst largely absent from previous tellings (especially in Wright’s autobiography). Four men receive particularly long portraits, tangents that take us pretty far away from Wright. The first—who stars in a cinematically horrific prologue and then returns 200 pages later for biographical treatment—is Julian Carlton, a black servant at Taliesin, the Wisconsin home Wright built after leaving his family in 1909 to live with Mamah Borthwick Cheney, the wife of a client. For reasons that have never become clear, one summer day in 1914 Carlton went berserk and gruesomely murdered Wright’s mistress and six others, then burned Taliesin to the ground.

Next up is Cecil Corwin, a young architect who befriended Wright early in his career and who, Hendrickson posits, may or may not have had a requited or unrequited crush on him. The third is Wright’s cousin, Richard Lloyd Jones, a Puritanical newspaperman who viewed his famous relative as a “house builder and home wrecker” but who, Hendrickson contends, was irrevocably seared by the catastrophic events at Taliesin. As he does with Corwin, Hendrickson tries to draw a conclusion about Jones and his relation to Wright—but this one seems even more far-fetched. After covering the lurid affair and the tragedy at Taliesin, Jones relocated to Tulsa, Oklahoma, where he witnessed—and enflamed, as Hendrickson demonstrates by quoting from the paper’s editorials and headlines—the city’s infamous 1921 race riot, during which white mobs destroyed a 35-block area encompassing one of the wealthiest black communities in the US, killing an estimated 100–300 people. Hendrickson speculates a link between the two events. “After August 15, 1914 [the day of the Taliesin tragedy], what had been a predisposition in a hubristic man for an absolutist way of thinking became only more absolute,” he writes about Jones. “There were ‘good Negroes’ … and bad [ones].’” Probing Jones’ apparent role as an instigator of the Tulsa violence, Hendrickson wonders: “Does ’09 lead to ’14 and does ’14 lead to ’21?”—seeming to implicate Wright’s infidelity in the racial terrorism that shattered Tulsa 12 years later. Conceding that he has no real proof for this theory, the author happily quotes a Wright scholar who terms this contention “Pretty Catholic. Pretty Faulknerian.”

The last man who occupies real estate in Hendrickson’s tome is Wright’s father, William. In presenting the “sad ballad” of this henpecked husband, Hendrickson corrects Wright’s own insistence that his father had deserted the family (he was, rather, given the boot by Wright’s mother). He also points out that in later years the architect seems to have come around to a softer view of his long-gone father by, for example, readily attributing his love of music to him and occasionally visiting his grave.

The story of Wright’s absent father is—along with the other three in-depth character sketches—presented as evidence to support Hendrickson’s central case that the architect’s soul ran deeper than his arrogance. Take this recounting of Wright’s arrival at Taliesin, via that agonizing train from Chicago, after the blaze. “At some point, after he had gotten in, perhaps taken off his coat, perhaps had sipped slowly from a glass of water, he went over, lifted the piano’s lid, sat down on the small stool that was covered with brocaded cloth, gathered himself, and began to play … Supposedly, he played through his crying,” he writes. “Back in Madison, in his unhappy childhood, he used to watch his beaten-down father … do the same thing: fold himself, almost disappear, at moments of great stress and disappointment and frustration, into his beloved Bach and Beethoven and Brahms.”

It’s a poignant picture—but is it really as revelatory as the author would like to imagine? It’s not news that geniuses can be complex and willful. Nor is it a surprise that the man who created such transformative buildings as Fallingwater, the Johnson Wax Headquarters and Taliesin West—all within a year or two of his 70th birthday—had a sensitive side. Fortunately, Hendrickson writes with verve and humor, with telling detail and abundant description. The reading is so pleasurable that it’s easy to forgive the cockiness—the Wrightian egoism, the unending confidence—of Plagued by Fire. What emerges from this particular set of fantastical, fictional, and factual ashes is its own kind of genius.