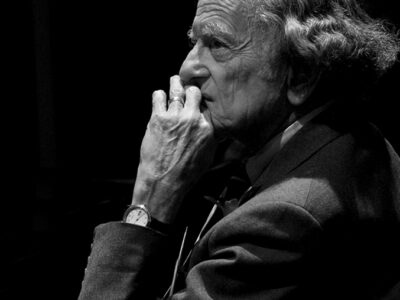

Interview with a rare Objectivist.

By Kimberly Bird

To scholars of U.S. poetry and of “Objectivist” poetry in particular, the name Carl Rakosi SW’40 is well known. Born in 1903 and only passing away in June of 2004, Rakosi’s life spanned the entire 20th century. Even with a nearly three-decade period when he dissociated from the poetry world, Rakosi was prolific, publishing eight volumes of poetry along with a large Collected Poems published by the National Poetry Foundation and a smaller collection of Poems 1923-1941, edited by Andrew Crozier and winner of a 1996 PEN award. He published enough prose to have a Collected Prose,also put out by the National Poetry Foundation, and was in touch with major poets and poetry editors across the decades, including fellow Objectivists Louis Zukofsky, George Oppen, and Charles Reznikoff, as well as James Laughlin, Marianne Moore, William Carlos Williams M’06 Hon’52, Ezra Pound C’05 G’06, Robert Duncan, and Allen Ginsberg.

Despite these accomplishments and the pleasurable readability of his poems, Rakosi is hardly known outside these scholarly circles. When I interviewed him in 2002 for the Regional Oral History Office (ROHO) at the University of California, Berkeley, he attributed the marginality of poetry in U.S. culture to the fact that “working people … simply don’t have the time to read poetry.” Of course, he acknowledged that there were still people who read and loved poetry but, in terms of cultural importance in the United States, Rakosi located poetry “in the same category as chess.”

As he delicately unfolded his life for me in our 19-hour oral history, it became clear that Rakosi had personally experienced the opposition between the poetry life and the need to make a living. In the early 1930s, Rakosi was coming into his own as an important poet. He was publishing in respected magazines like New Masses and Little Review, and, in 1931, Louis Zukofsky chose to include his work in a special issue of Poetry magazine. Zukofsky himself had been handpicked as guest editor by literary giant Ezra Pound to breathe new life into the magazine by showcasing the nation’s best young poets as a new poetry movement. That “Objectivist” issue of Poetry was followed by an anthology, and the “movement” secured its place in poetry history.

However, by the time New Directions issued his first book, Selected Poems, in 1941, Rakosi had already decided poetry wouldn’t support his family and he couldn’t work and write poetry. In a society just emerging from the Depression and heading into World War II, Rakosi felt he would make more of a difference with his social work, where he was “able really to help another human being,” than with his poetry, which was becoming increasingly difficult to place as journals like New Masses saw it as “self-indulgence” in a time of crisis.

Rakosi kicked his poetry life as one would an addiction. He explained:

I became ill, actually. I couldn’t stand it for two years. I thought, “Oh God, I’m going to die.” But, I had to do it, to stop. So, I stopped reading poetry and stopped writing it. I just put myself totally into the social work world, and that’s a world that can keep you absolutely absorbed. In a way, it was good and bad, but it’s a great occupation, and one that gives one great satisfaction. So, I was in that world totally—until I started to write again, in 1969.

Rakosi might never have started writing again had it not been for Andrew Crozier, a graduate student at SUNY Buffalo who had heard of Rakosi from his professor, poet Charles Olsen. Crozier had found every poem Rakosi had ever published and sought him out for more. By that time Rakosi had already had a full career in social services and his children were grown. Crozier wanted to know if Rakosi still wrote poetry and, after reading his letter, Rakosi wanted to know, too. He sat down and composed “Lying in Bed on a Summer Morning,” which begins with an idyllic view from a bedroom window and continues:

And all at once the early birds

all break out chirping

as when the bidding opens

on the stock exchange.

Then one,

the long sweet warble

of a finch.

Oh stay!………

And then a chant from down the street,

two boys triumphant,

very small and thick glasses:

“we got a bird nest!”

“we got a bird nest!”

But a younger brother

left behind and clobbered

when the mother was not looking

saw his chance to singsong back

(Ah sweet revenge):

“But

a woodpecker didn’t make that nest!”

A contrary air.

It is gone.

And the blue sky,

clear as in Genesis,

Holds.

“To my amazement,” Rakosi said, “that poem was no different from poetry that I had written more than 20 years before.” He was a poet again and did not stop writing until the final days of his life.

In conducting this oral history, I had the opportunity to enter Rakosi’s living room and world for two thought- and laughter- provoking hours every Wednesday afternoon for nearly three months. At the time, Rakosi was 99 years old and, while the passage of time certainly affects the functioning of memory, Rakosi’s mind was acute and athletic.

The oral history, A Century in the Poetic Eye: Carl Rakosi on Poetry, Psychology, and World Affairs in the Twentieth Century, is now accessible on-line through ROHO’s website: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ROHO/projects/arts_ca/.

We began with Rakosi’s childhood in Baja, Hungary, and his family’s immigration to the United States—including his boyhood in Kenosha, Wisconsin, and his schooling in Gary, Indiana. A precocious student, he wound up at the University of Chicago when he was just 16 before heading to the University of Wisconsin, Madison, where he really became a poet.

Although Rakosi claimed to have little use for the theoretical, he explained his abstract notion of the “poetic eye”—the special capacity to see “things with a creative eye, where you see beyond the literal” that differentiates poets from the rest of the world. Pointing to a painting on the wall opposite where we sat every week, he spoke of the possibility for movement he saw in the composition and the feelings he developed as he looked at the painting, rather than describing the lines and colors as they were. The “poetic eye” meant participating in the creation of meaning rather than merely determining a meaning that was already there.

Throughout the interview, Rakosi engaged thoughtfully on historical and current events, including the establishment of Israel, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the September 11 attack on the World Trade Center, and the invasion of Iraq, which he saw looming on the horizon as we worked in 2002. At the start of our session on September 12 of that year, he praised Bush’s speechwriter for the quality of the speech delivered in Washington but noted: “it was clearly a war message that we’ve got to invade Iraq … I sense from my experience with propaganda during World War I and World War II, that’s what we can expect now.”

Jewish history and anti-Semitism became recurring themes for Rakosi, who discussed the fate of his relatives in Hungary during World War II and his return there to the Holocaust memorial much later in life. He probed the history of anti-Semitism in the U.S. and held back nothing of his views of other poets in this light. According to Rakosi, in the 1920s through the 1950s, the literary world was rife with anti-Semitism, the only exception being Sherwood Anderson. Furthermore, Rakosi explained:

Eliot was one of the absolute worst. He was worse than Pound in my opinion. Eliot at one time suggested that Jews should not live in the same city as non-Jews. They should be somewhere else. I grew up with— knowing all of that, and I knew how to live with it. You cope with it. My life was not in danger. I just had to do other things.

One way that Rakosi “cop[ed]” was to change his name officially to Callman Rawley, a name he chose for what he considered its Americanness. Yet, probably because of his pre-name-change “Objectivist” notoriety, he remained Carl Rakosi in the poetry world.

Looking back over his long 20th century, Rakosi took the massive technological advances that he witnessed in stride. Far from feeling overwhelmed or left behind, Rakosi considered the Internet as a possible future for poetry as small presses struggle to stay alive. He even celebrated his 99th birthday via live web broadcast connecting him at his San Francisco dining-room table to co-moderators Tom Devaney and Al Filreis at Penn’s Kelly Writers House and to others tuning in around the world.

As he narrated his life for the oral history, Rakosi consistently figured himself not as the hero of his own stories but as an innocent bystander to whom interesting and surprising things happened—other poets such as Pound and Zukofsky recognized his poetry’s worth and published it; Crozier gave him the spark to break his poetic silence; a mysterious check for $5,000 arrived in the mail as a kind of anonymous fellowship; and so on.

Much of Rakosi’s poetry alternated between satirical and meditative modes. The latter became most appealing to him in his final years, and, during our sixth session, Rakosi confessed that he had just come down from “a little binge” of writing 13 meditative poems. While he felt that he hadn’t written political poetry in some time, a good portion of Rakosi’s work, including much of his meditative poetry, has a political bite that is as sharp as it is humorous or thought provoking—but this poetry is not world-weary. For Rakosi, it was not an option to throw up his hands in anger and political disillusionment.

From his writing and this oral history one can glean a few simple ideals for living that helped him survive a tumultuous century: look squarely at the world and people around you, think deeply, stay engaged, nourish community and family, and laugh to make it all better for everyone.

Kimberly Bird C’94 is a writer who recently earned her Ph.D. in History of Consciousness at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Her 2002 interview with Carl Rakosi was published last year by the Regional Oral History Office of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.