The University’s new Climate Action Plan is good for the environment—and won’t hurt Penn’s bottom line, either.

By John Prendergast | Illustration by Chris Sharp

Sidebar | An Efficient Use of Resources

At least until she got self-conscious and started to laugh, the young woman perched on the wall outside Houston Hall wearing an orange rain-poncho was vaguely reminiscent of the Statue of Liberty. Rather than a torch, though, she held aloft a hand-painted sign. It showed the word THINK beneath that traditional signifier of a bright idea, a light bulb. But this light bulb was not the familiar, well, bulbous shape of an incandescent but one featuring the curved tubes of an energy-saving compact fluorescent model.

With her other arm, she urged passersby inside Houston Hall to join the celebration—relocated from College Green due to a drizzling rain—marking the release of the University’s Climate Action Plan, which lays out Penn’s strategy for reducing its carbon footprint and becoming more environmentally sustainable. Development of the plan was set in motion when Penn President Amy Gutmann signed the American College and University Presidents Climate Commitment (ACUPCC) in February 2007.

The ACUPCC is an effort to leverage the $317 billion higher education industry’s influence, skills, and economic clout to advance efforts to counter global warming—starting with their own environmental impacts. Signatories ackowledge that “global warming is real and is largely being caused by humans” and that a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions of 80 percent is needed by 2050 to “avert the worst impacts.” Institutions that sign on pledge to perform a comprehensive inventory of their greenhouse gas emissions within a year, and, by two years, to “develop an institutional action plan for becoming climate neutral.” Participants also had to pick among a series of short-term actions to cut emissions (several of which the University was already doing), and promise to make the results of the inventory, the action plan, and subsequent progress reports publicly available.

As of this fall, more than 650 schools have signed the commitment. Penn was among the earliest; it and about 350 other institutions were supposed to submit their plans by September 15. One reason for the September 16 rally was to celebrate meeting that deadline.

Inside Houston Hall’s Bodek Lounge, students, some of them holding more signs (“Red and Blue Makes Green,” “We Want to Compost Now,” “Love Trees,” “Learn to Sustain Our Earth,” “Live Clean, Play Dirty”) along with staff, faculty, and community members paused at table-top exhibits around the room’s perimeter offering information on Penn’s various green initiatives. At one table people could compare the feel of traditional caps and gowns with the ones made from 100 percent post-consumer recycled plastic bottles that next year’s graduates will suit up in for Commencement. At others they could meet members of the student-run food-sustainability group FarmEcology, pick up a copy of the course list for the University’s new undergraduate minor in Sustainability and Environmental Management, or learn about the “virtual” environmental umbrella-group Green Campus Partnership (www.upenn.edu/sustainability). The most popular table seemed to be the one set up by Penn’s new food vendor, Bon Appetit, chosen in part for its sustainable food practices, where locally grown apples and cider were being handed out.

“Penn is proud to be an environmental leader among American colleges and universities,” President Gutmann said in a statement announcing the plan’s release. “The health of our planet depends on our actions and Penn is committed to leading higher education’s green revolution into the future.”

At the rally, she lauded the document as “the finest university climate action plan on this planet,” and praised Anne Papageorge, vice president for facilities and real estate (FRES), for her leadership in bringing together the University’s various constituencies to create it. Papageorge chaired the Environmental Sustainability Advisory Committee (ESAC), made up of staff, faculty, and students—more than 40 people in all—responsible for developing the plan’s recommendations.

Gutmann also singled out Dan Garofalo GAr’87 G’03 LPS’08, the FRES staffer who serves as Penn’s environmental sustainability coordinator (ESC)—a position mandated by the ACUPCC—as the “heart, mind, soul of this report,” and recognized the faculty and student leaders who served on the ESAC for their contributions.

Penn’s “special talent” for doing more with less “resonates ever more powerfully” in the context of the environment, Gutmann added. The Climate Action Plan is all about “achieving a more innovative Penn, a more intellectually exciting and integrated Penn, and a more sustainable Penn, with less use of carbon-based fuels, less waste, and less harm to the environment.” She called the document a “roadmap for doing what we do best—imagining a better future for ourselves and the world, translating our vision into reality by integrating our scholarly expertise across our 12 schools in the area of sustainability, and putting our knowledge to work by engaging communities all over the world.”

The plan traces Penn’s history of environmental awareness and increasing engagement with issues of sustainability in its design and operational practices, and includes long-term projections aimed at reaching climate neutrality by mid-century. (The complete text and an executive summary are available at the GCP website, along with lots more information.) But the main thrust is a series of actions that will significantly shrink Penn’s carbon footprint over the next five years:

Penn will reduce its energy consumption by 5 percent this year and 17 percent by 2014, avoiding 86,500 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (MTCDE) and saving an estimated $13.7 million along the way.

As the campus is enhanced with developments like Penn Park on the former postal lands, which will add more than 20 new acres of green space, new construction and renovation projects will be designed to meet strict standards for energy efficiency developed by the U.S. Green Building Council and the Environmental Protection Agency and Department of Energy.

Campus recycling rates will be doubled, from 20 percent to 40 percent, by developing comprehensive policies, providing more education, and ensuring that proper receptacles are widely distributed.

Through discounted fares, more (and more secure) bicycle racks on campus, and other incentive programs, walking, biking, carpooling, and use of public transportation will be encouraged, with the goal of getting more than half of Penn’s population to stop driving solo, up from the current 40 percent who choose alternative means of transport.

Courses, seminars and workshops, and other educational opportunities will be made available to provide a robust academic component, so that all Penn students can learn about climate change and environmental sustainability. Besides the new minor, plans call for the 2010 Penn Reading Project selection to relate to sustainability, for example.

Finally, a comprehensive communications program will be put in place to ensure that Penn’s environmental goals, progress toward achieving them, and ways to participate will be disseminated widely and in a variety of formats.

An Aspirational Goal

FRES’s Papageorge calls Penn’s decision to sign on to the climate commitment a “natural” step, given the University’s “deep-rooted tradition in sustainable landscapes and a sustainable approach to its operations, design, and planning.” She adds that the commitment is “very consistent” with the Penn Compact and with the University’s campus master plan, Penn Connects.

“As Dr. Gutmann has said, this [is a matter of] moving our principles into the spotlight and pushing the dialogue and feeding the progress of this initiative through Penn’s circle of influence and through the attention we get as a leading institution.”

Skeptics have accused the ACUPCC of being too long-term and vague in its goals, and a number of schools that had taken an early lead in addressing sustainability issues, such as Harvard, Yale, and Stanford, passed on signing the commitment.

(So far, Penn and Cornell are the only Ivies on board. However, there is considerable information sharing and collaboration among the sustainability coordinators within the Ivy Plus group, which includes Johns Hopkins, MIT, Stanford, Georgetown, the University of Chicago, and Duke, in addition to the Ancient Eight. “It’s really rewarding,” says Garofalo. “We share everything—you know, best practices, no jealousy and no pride of ownership.” )

“Different leaders see this challenge differently,” says Papageorge. While the practical feasibility of the ACUPCC’s ultimate goal—reaching climate neutrality, or the equivalent of zero emissions, by 2050—was a sticking point for some, “Dr. Gutmann talks about it as aspirational and as guiding our research and education in this direction.”

After Penn signed the commitment, the ESAC was charged with getting input from across the University, researching best practices at peer institutions, and developing recommendations for the climate action plan. Subcommittees were set up to address the main areas for emissions reductions—utilities and operations, physical environment, transportation, and waste minimization and recycling—and to develop recommendations for academics and communications components.

The structure worked well in balancing broad representation with efficiency, Papageorge notes. “In the first few meetings we were all over the map and [received] many more suggestions than we would ever be able to accomplish,” she recalls. “I realized we weren’t going to get very far that way.” Still, even after the task was divided up among the different groups, the initial glut of recommendations—dozens per subcommittee—needed to be pared back considerably for the final document, with the idea that “we’ll add more as we accomplish certain things,” she says.

Garofalo functioned as the point person for the planning process, supported by an assistant, and, eventually, by a team of sustainability associates made up of current students and recent graduates serving as interns at FRES (see sidebar).

He started as ESC in April 2008, but had been working as an architect and planner at FRES since 2002 and has been involved in sustainability issues in various ways for a good part of that time. The job of the ESC, Garofalo says, “is about providing tools throughout the university, and the strategies for implementing behavior change and institutional change,” as well as serving as a liaison to key constituencies within the university and external groups like the media.

Garofalo was tapped to be Penn’s representative on the local chapter of the U.S. Green Building Council when it was getting started several years ago. He was a founding member of that organization, the Delaware Valley Green Building Council, and currently serves as its chair. “It was a very dynamic group,” he recalls, adding that attending the monthly meetings “was like a tutorial in green design and construction.”

He described the Council’s work as “perfectly consistent with everything I’d done up to that point as a design professional and also working here in facilities, but by shining a spotlight on those issues, it really kind of captured my enthusiasm amd interest.”

The department gradually internalized these ideas, he says, and around the time that Anne Papageorge came on as FRES VP in 2006, “a lot of things came together at the same time,” sparked as well by growing student interest and nudging by the facilities committee of Penn’s trustees, many of whose members are design and construction professionals, real estate developers, and building owners. “They were saying, ‘I hear [about these issues] in my private business. What’s Penn doing?’” Finally, President Gutmann and Executive Vice President Craig Carnaroli W’85 “began to hear what other schools were doing and express an interest themselves. That’s when we really started making a concerted focus on not just design and construction, but all the other aspects, too—transportation, and waste minimization and recycling, and academics, and all those other issues.”

It was at a national conference for the GBC that Garofalo recalls meeting Anthony Cortese, a former university professor and environmental official in Massachusetts, who had founded a group called Second Nature devoted to promoting environmental sustainability at college campuses. At some point, “he had this brainstorm that if he could leverage 40 or 60 or 80 college presidents who would sign a commitment to reduce carbon emissions, that would be very significant in order to push for national legislation, or to go in front of governors and state legislatures,” Garafalo says. “Of course, it succeeded beyond their wildest dreams.”

Penn’s signing was something of a coup for the group, he adds. Many of the first adopters were smaller teaching colleges, without major research components—Middlebury, Oberlin, the College of the Redwoods, and of the Everglades—“the natural audience,” Garofalo calls them. Penn’s signing, along with that of Arizona State, which has one of the biggest student enrollments in the nation, represented a “tipping point for the organization, because it really jumps your credibility.”

Sources and Solutions

By the time time Penn was approached about signing the commitment, the timing was ripe. As on many campuses, sustainability had become a byword among environmentally aware students. Both the Undergraduate Assembly (UA) and the Graduate and Professional Student Assembly (GAPSA) had established standing committees on sustainability. The student group FarmEcology was working to promote local and seasonal foods, and helped start a farmers’ market at 36th and Walnut streets. Some 45 tons of material was diverted from the waste stream—that is, not dumped on sidewalks after classes ended and leases ran out—through an end-of-year moveout recycling and reuse program called PennMoves. Sales of the students’ trash became treasure for West Philadelphia charities, which netted $30,000. In late 2006, the Penn Environmental Group, which was founded in 1971, a year after the first Earth Day, gave a presentation on sustainability opportunities at Penn to President Gutmann at a meeting of the campus advisory group, the University Council.

Penn had taken a number of steps to become more energy-efficient in its operations—for example, setting up a centralized control center for some campus utilities at FRES—but unlike a number of other schools, the University does not generate its own power, which limits its ability to reduce emissions at the source. That’s one reason Penn has become a leader in the purchase of renewable energy credits (RECs), offsets that help create a market for non-carbon energy sources like wind power. Over the past several years, Penn has emerged as the biggest purchaser of wind power through this means among higher education institutions, with a string of awards from the EPA to show for it. The University currently buys 193,000 kilowatt hours annually, an amount that has grown four-fold since its initial purchase in 2001. Penn’s purchases have provided financing for 12 windmills at Bear Creek, Pennsylvania, and continue to support windpower projects across the country.

Since electricity from all sources flows through the same grid, there’s no way to tell where an individual’s or institution’s power is coming from, and RECs have been criticized as a means of, essentially, buying your way to sustainabilty. A recent article in the Chronicle of Higher Education noted that “some perceive [RECs] as an easy way to meet the letter but not the spirit of the commitment.”

The charge is that, “until an institution is reducing its own energy load, it’s not making a credible effort to be sustainable,” Garofalo explains, “which is legitimate—that’s always the first goal.” But Penn’s purchases are being done in tandem with a serious focus on reducing the emissions it can control, he adds. The EPA also supports the idea of giving credit for emissions reductions through the purchase of RECs as a means of spurring the development of more renewable sources.

By committing upfront to purchase these offsets, “we believe we are promoting the development of the wind power industry,” says Papageorge. “It is advancing the implementation of accessible renewable technologies.”

In 2006, Penn also began tracking its own carbon inventory, working with the TC Chan Center for Building Simulation and Energy Studies, a collaboration between Penn and China’s Tsinghua University housed in the School of Design. Data from the inventory helped support the decision to sign the climate commitment, and the Center went on to research and draft the carbon reduction recommendations included in the final plan.

The involvement of such respected scholars as Center Director Ali Malkawi and William Braham, an associate professor and interim chair of the Department of Architecture who is affiliated with it, also helped secure “buy-in” among Penn’s various constituencies. “They were critical,” says Papageorge, “because of their credibility on the subject matter.”

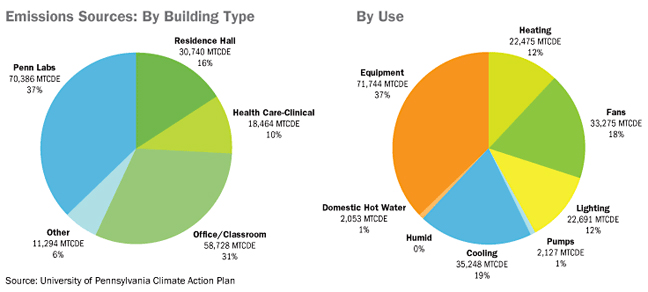

It quickly emerged that buildings were far and away the main offenders at the University, as at most schools, accounting for 86 percent of emissions. Next up was air travel by Penn community members, at 8 percent, followed by commuting, solid-waste disposal, Penn-owned vehicles, refrigerant leakage and replacement, and landscape management, which together make up the balance.

One piece of good news the carbon inventory revealed was that, because of efficiency upgrades at Penn’s steam supplier and the purchase of RECs, Penn’s carbon footprint had actually shrunk somewhat since 1990, despite campus growth, which put the University in compliance with the Kyoto Protocol, the international agreement that called on industrialized nations to reduce emissions by 5 percent from 1990 levels by 2012.

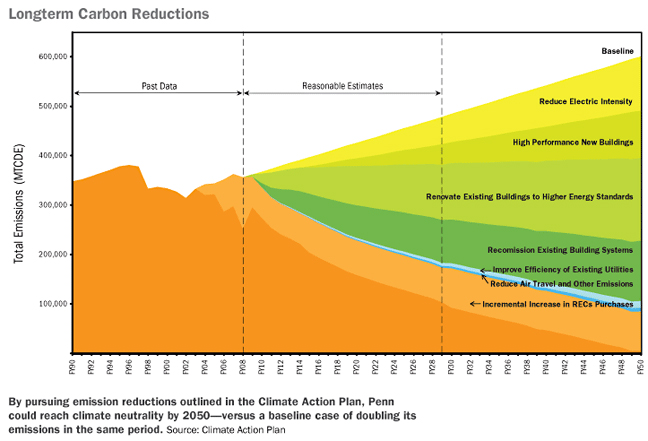

Long term trends, though, told another story, showing that—absent any new reduction efforts—the University’s emissions would nearly double by 2050, as a result of the incremental growth of the campus’ size and population and the proliferation of new electronic devices, known as electrical intensity (watts per square foot), which together account for a 2.5 percent annual increase in energy demand. The longer such trends are projected outward, the more speculative they become, but, the plan notes, “as the journey to a reduced carbon footprint will take many years, a long-term projection is needed to provide a target for carbon reduction scenarios.”

“We don’t know what’s going to happen” by 2050, Garofalo admits. That’s why Penn’s plan is very focused on one and five-year targets, with plans to reevaluate in the future.

In any case, the solutions are the same, regardless of the timeline. To attack the electrical intensity issue, the plan calls for a mix of behavioral changes and equipment purchases to reverse the trend toward incremental increases in power consumption. To limit emissions from new and existing buildings, all future construction and renovation projects will have to be certified as LEED Silver, according to a ranking system developed by the U.S. GBC. LEED stands for Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design; Silver is the second rating on the scale, after simple certification and before Gold and Platinum. (All Penn’s current building projects comply with LEED Silver, and the new $20 million horticultural center under construction at the Morris Arboretum is working toward a Platinum rating.)

Projects will also be measured against another standard, the EnergyStar system sponsored jointly by the EPA and Department of Energy—familiar to anyone who has bought a household appliance. New buildings must qualify for EnergyStar 90, which means that they are more energy-efficient than 90 percent of similar buildings, and renovations will meet EnergyStar 75 standards (better than 75 percent of comparables).

In many instances, building to these standards increases initial costs, which is why they have often been “value engineered” out of designs in the past, at Penn and generally, Papageorge says. However, the savings in maintenance and operations more than make up for it, she adds.

To get an idea of the potential energy savings among the 182 buildings on campus (excluding the health system), the Chan Center developed a building performance assessment tool that used information from surveys by School of Design graduate students and construction documents to rank buildings in terms of efficiency and carbon emissions.

In 2007, Wharton’s Huntsman Hall and the dental school’s Schattner Center were selected for a pilot project from among a group of buildings using more energy than anticipated. About 200 needed repairs were identified and completed, and then meters were installed to measure savings. It turned out that the repairs reduced energy use enough to save $500,000 within the first year—earning back their cost within less than six months. Another 14 buildings were studied last year and this year, ranging from the venerable Houston Hall to the engineering school’s home, Skirkanich Hall, which opened in 2006. In 2009 and beyond, FRES will be working with clients in the schools and center to retrofit eight buildings annually.

By 2014, the plan projects emissions reductions of just under 86,500 metric tons, yielding savings of almost $13.7 million, just about all of it related to cutting energy use in buildings. Energy savings, costs, and monetary benefits for the other elements in the plan are either not applicable (academic, communications) or too uncertain to quantify at this point.

Initial funding for improvements—modest, given the economic climate, says Papageorge—will come from existing budgets and a variety of other sources, with conservation expected to be the source of future expenditures “at least for the next year or two, until we come out of this economic crisis.”

Reductions in consumption should lead to monetary savings. “Why pay an outside entity these dollars when we could be using them to upgrade mechanical systems?” Papageorge asks.

Still, the balance between spending and emissions reduction is not always so clearcut. In one case, there was a debate over how stringent to make the standard for building renovations, Papageorge notes, with some pushing for Energy Star 90 as opposed to Energy Star 75. “We looked at what that would cost and what the return was, and it was not very convincing. I said to my staff, ‘Wouldn’t it be better to get more of our portfolio to Energy Star 75 for the same amount of money? And then once we’ve gotten more of our portfolio there, then we can up the standard to 90,’” which is the recommendation that appears in the published plan.

“There are many proposals out there that don’t have a very good return on investment,” Papageorge says. “It’s not that they’re not nice to do one day, but with limited resources you are looking to put your investment in the place where you can get the maximum—or a good—return in a short payback period.”

Personal Choices

Penn’s buildings account for the lion’s share of emissions and will be a major focus for reduction efforts, but such improvements, which are “about highly technical engineering solutions to reduce energy demand,” don’t do much to engage the community, Garofalo says. So, while you “have to hit the big emissions sources,” it’s also critical to do a good job on other elements, like public transit, providing safe and secure bike racks, food sustainability, and especially recycling. Though it’s a small contributor to energy use, “Everybody says if you don’t do recycling well, no one believes you about the other stuff,” he adds.

And even reducing the emissions from buildings will be as much a matter of behavioral changes as technical fixes. “I don’t know how many red lights are on when students go to sleep,” Garofalo says, referring to the myriad electronic devices perpetually in standby mode in dormitories across campus, from flat screen TVs to game consoles to computers and cell phone chargers. “We have to do a better job of policing ourselves,” he says.

Just like students, Penn employees need to alter their habits as well by doing things like turning off their computers at night rather than putting them to “sleep”—it isn’t true that booting them up again uses more energy, really—and making double-sided copies. “A lot of things that personal choices will change at Penn can equal big institutional repair and retrofit projects,” he says. “They are two sides of the same coin, neither bigger than the other.”

One effort aimed at behavior change is the new Eco-Reps program, being rolled out in three of Penn’s 12 college houses as a pilot this year, in which self-selected students will be trained to serve as the “sustainability go-to person” in their house. “Every month we’ll invite those students down and talk to them on a specific topic—energy, transportation, food, consumer choices, heating and cooling, waste and recycling, things like that—and try to provide them with the tools to communicate to the 30 or 40 students that they’re ‘responsible’ for.”

Similar training programs will be implemented for FRES employees and other professional staff, possibly starting with building administrators. “For the price of a lunch we can get a lot of information out and distributed that will provide tips for behavior change.”

The Green Campus Partnership website is another focus for spreading the word. “People knew we recycled at Penn,” Garofalo says, by way of example, but they didn’t know where to deposit recyclables, what to include, or why it was important. “That’s just all about information. Because given the right information, and physically a place to put things, people will generally recycle.”

With the exception of scattered student complaints about low-flow showerheads in dormitories, energy-saving measures have been well received so far, Papageorge reports. “We are learning that we have to get information out before we do work, so people understand why they’re being asked to make this change,” she says. “The other thing we’re hearing is that we need to show people results to continue the momentum, so that’s part of what we’re working on now, creating the monitoring structure.”

A twice-yearly report will assess progress on the climate plan’s goals, and determine whether and how they need to be scrapped, modified, or added to to improve performance.

A number of programs are already under way. As part the ongoing effort to retrofit Penn’s building stock, a pilot project has shown that a system called Aircuity could make the air-exchange process in laboratory buildings—a major energy drain—both more effective in protecting lab personnel and more energy-efficient. Besides the launch of the Eco-Reps program, 40 new students participated in PennGreen, a four-day pre-orientation program that introduced them to Philadelphia’s leading environmental initiatives before classes started. Administrative actions cited in the plan include hiring the environmentally friendly Bon Appetit for dining services, a policy by the University’s purchasing office to direct buyers to “sustainable sources,” and the move to provide Commencement regalia made of recycled materials. Finally, to encourage innovative proposals on sustainability, a Green Fund has been established that will award up to $50,000 to any group in the Penn community for ideas to change behavior, educate, or implement technical solutions that reduce campus emissions and improve sustainability.

At the rally in Houston Hall, President Gutmann noted that the plan offered a “myriad of suggestions” for individual action, and called on all members of the University community to “not let a day go by without doing something” to help make Penn a leader in environmental sustainability “and show that we can have fun doing it.”

“This is a mission that is both educationally important and absolutely critical for our planet,” she said, pledging to make Penn the “greenest urban campus” in the country. “And while we continue to bleed red and blue, we also will dream a green dream for Penn. We are putting our minds to work and making that dream come true.”

SIDEBAR

An Efficient Use of Resources

“[W]ork to date has been carried out by a minimum of

full-time staff and temporary sustainability associates.”

—Introduction, University of Pennsylvania Climate Action Plan

Creating Penn’s new blueprint for environmental sustainability (see main story) involved individuals and groups from all corners of the University, but no role was more vital that that played by a dozen or so current students and recent graduates who interned with facilities and real estate (FRES) in 2008 and 2009. These “sustainability associates” were involved in virtually all aspects of the planning process, from conducting research on Penn’s carbon footprint, to helping develop recommendations and drafting large chunks of the plan, to bicycle-messengering last-minute edits across campus and incorporating them into the final document—anddesigning a website and other communications vehicles to share the plan and keep the Penn community informed of progress.

In a group interview shortly after the plan was submitted, and email followups with some who weren’t present, they commented on the experience.

Before she went off to medical school this fall, Sarah Abroms C’08 had worked with Environmental Sustainaibility Coordinator Dan Garofalo as the assistant ESC. The biology major arrived on campus with a “passion for the environment” and embraced the concept of sustainability as a member of the Penn Environmental Group and while serving in the Undergraduate Assembly. “The first time a peer explained it to me, it just made sense,” she says. As a student, she served on two of ESAC’s subcommittees, and as the assistant ESC she helped coordinate the various subcommittees and served as the liaison to the student groups on campus.

Of the finished plan, Abroms says, “It was a successful team effort made by students, faculty, and staff” that could serve as a “model for future projects and endeavors.”

Unlike Abroms, Steve Belfiglio C’07 denies being a “hardcore environmentalist or tree hugger” as a student. A communications major, he first became intrigued by the concept of sustainability “because it requires more than just selling someone on a tagline or a brand. It requires convincing people to change their behavior—habits that have been ingrained in them since childhood—which I viewed as a pretty inviting challenge after realizing how far we have to go as a society.”

His involvement came about by chance when he met Dan Garofalo while helping his girlfriend make a video for her environmental studies class. “He was looking for help and asked if I was interested in joining the team.”

Since starting in the summer of 2008, he’s moved from working on recycling issues to broader communications efforts. “My responsibilities have included re-designing the Green Campus Partnership website and developing educational materials, from presentations to posters to videos, for use across the campus, and the soon-to-be-launched Green Campus Partnership bi-monthly e-newsletter, the Red and Blue On College Green,” he says.

Belfiglio says the plan’s goals are “ambitious, yet attainable,” and subject to change—a point that many of the associates made. “The great thing about the plan is that it’s a working document,” he says. “Although it’s a ‘finished’ product, we will look to expand upon it once we begin implementing various projects and initiatives en route to meeting our goals.”

After getting her undergraduate degree in architecture, with a focus in environmental studies and sustainability, from Arizona State, Lydia Nicole Hermo GAr’08 came to Penn for her master’s, and after graduation started working for the TC Chan Center for Building Simulation and Energy Studies, where she was involved in calculating Penn’s carbon reduction plan for 2050 and assessing building energy performance. She then joined the sustainability team, helping to craft the plan’s utilities and operations recommendations.

“By signing the [climate] commitment, Amy Gutmann really made us have to be accountable, which is something that will help the plan move forward in the future,” Hermo notes. “We will have to report our emissions every year—an honest telling of what we’re doing and what we’re not doing and how much you need to invest to move forward.”

Sarah-Jane Littleford C’09, who succeeded Sarah Abroms as assistant ESC for the summer of 2009, grew up in Zimbabwe. As an undergrad, she designed her own major focused on sustainability issues, “which incorporated economics, political science, anthropology, environmental studies—really a whole host of subjects—and that was fantastic that Penn gave me the flexibility to do something like that.” Past internships have included working for a mining company and looking at water resources in West Virginia for the EPA. “When the opportunity came to expand my education here at FRES and work with the American College and University Presidents Climate Change Commitment, which incorporates so many different issues, I really jumped at it,” she says.

Brittany Bonnette C’08 started work as an associate in May 2008, after graduating with majors in urban studies and PPE (philosophy, politics, and economics). An avid cyclist with an interest in “making cities better places,” she drafted the transportation section of the plan and also became “the main organizer,” according to Garofalo, as the document was compiled, edited, and approved by the Environmental Sustainability Advisory Committee chairs and other University leaders during the final stretch toward the submission deadline of September 15.

Bonnette expresses confidence in the depth of Penn’s continuing commitment—“We have enough people throughout the institution,” she says. “There are people holding us accountable!”—but was a bit less sanguine about other players. “I’m concerned that federal and state policies may not keep pace,” though so far those policies seem “pretty positive,” she adds.

Much of the actual “wordsmithing” of the plan document, Garofalo adds, was done by another associate, Sarah Fisher GCP’09, a global and environmental politics major as an undergrad, who got her master’s in city planning at Penn in May. She came to FRES after working for the executive vice president’s office on a paper comparing sustainability efforts at Penn’s peer institutions. Fisher calls the opportunity to work on the plan “a perfect compilation of all the things that make me excited and that I hope my career is oriented around.”

Julian Goresko LPS’09, who majored in environmental studies as an undergrad at Penn and is now in the master’s program, jokingly describes his contribution to the planning document as one “fundamental page on West Philadelphia’s revitalization,” and racing corrections across campus on his bike. Looking ahead, he expresses the hope that the ACUPCC will awaken all “big impacters” to their responsibility to the environment. “I see more and more sustainability reports from companies and institutions,” he says. “I think we’re starting to see a cultural shift taking place.”

“It’s a global cultural shift, not just here in the U.S. It’s just going to gather steam and carry on and snowball,” adds Littleford. “We’ve started early and started well.”—J.P.