The next big thing for Philadelphia photographer Jacques-Jean (JJ) Tiziou C’02 is really big. Think 50,000-square-feet big. That’s the approximate total area of the Philadelphia International Airport’s I-95-facing parking-garage façades, which are about to be prepped for the upcoming installation of the Mural Arts Program’s largest mural to date. The mural’s theme, “How Philly Moves,” is Tiziou’s brainchild, a photographic tribute to the city’s diverse and thriving dance scene.

Tiziou has been an honorary member of Philadelphia’s performing-arts community since 2003—the year he made it a personal goal to attend every single event of the Philadelphia Fringe Festival and “photograph the crap out of it,” as he puts it. “I went and shot like 30,000 frames over three weeks. I shot every conceivable performance and every backstage moment and every technician loading things and every administrator filing things.” He speaks quickly, as if keeping pace with the madness of such an endeavor. “That’s when I really fell in love with the community.”

His initial infatuation matured into an enduring commitment to photographing local performing artists of all sorts—not just dancers, but singers, musicians, actors—and to capturing the beauty and value inherent in everyone who contributes to these art forms: amateur or professional, assistant or performer.

That inclusivity flavors his approach to photographing subjects outside the arts world, as well. Whether he’s documenting grassroots activism or shooting studio portraits, Tiziou is adamant in his stance that “everyone is photogenic.”

“We’re fed this awful idea that the celebrity on the cover of the magazine is somehow more photogenic, more special, than we are,” he laments. “The next time you’re in the checkout line at the grocery store, take a look at that magazine, then take a look at the cashier. Imagine the cashier takes the model’s place, with as many assistants and lights, and as much retouching, and imagine the photographer was able to make them just as comfortable in that weird outfit in that artificial studio setup—they’d be just as beautiful.”

It’s not surprising, then, that Tiziou cast a wide net when enlisting dancers for this current project. From its inception in the spring of 2008, “How Philly Moves” was open to anyone who self-defined as a dancer, whether they danced at home in front of their bedroom mirror or as a member of a professional troupe. In its earliest iteration, the project was a response to a SEPTA commission for a public art installation in the renovated Market-Frankford Line station at 46th and Market streets.

In partnership with friend and sculptor James Peniston, he conceived a dance-inspired mixed-media submission. Some 70 dancers showed up to be photographed. More than 40 volunteers surfaced, helping with all manner of chores—scheduling the shoots and even offering a hand with the installation should their submission have won.

It did not.

“But there was so much of a community that had helped me create this thing,” Tiziou says. Determined not to quell their enthusiasm, he continued the shoots through that fall as a pet project. By the end of 2008, however, he had run out of the time and resources needed to take it any further. Months passed, and he focused his attention elsewhere.

“Then someone forwarded me the email about this Mural Arts thing,” he recalls.

As the story goes, Philadelphia’s deputy mayor for transportation, Rina Cutler, was sitting in traffic on I-95 one day when the idea hit her. The airport’s parking garages are the first glimpse of the city for travelers heading north—“a perfect canvas for a gateway-to-the-city project,” she thought. Jane Golden, executive director of the Mural Arts Program, agreed.

They put out a request for proposals that garnered responses from artists across the country. Tiziou immediately sensed the synchronicity between his project and the Mural Arts Program’s goals. He spent the next few months trying to convince the program’s committee.

More than 400 dancers responded to Tiziou’s invitation to participate in “How Philly Moves.” Sixty individuals and pairs were selected to perform at the weekend shoot in early March, a group intended to represent every Philadelphia neighborhood and as many different styles of dance as possible.

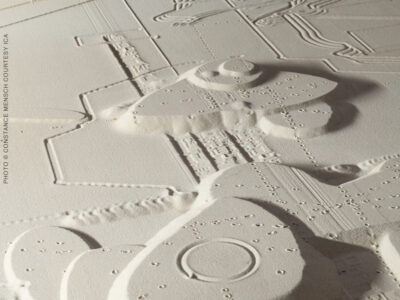

Together with dancers who participated in the previous shoots, nearly 200 have been photographed. About 20 will grace the garages’ facades next summer—their likenesses skillfully distorted with 3D rendering software to account for gaps and angles in the concrete.

In the waning hours of a Sunday afternoon, the final 12 dancers took to the stage in the Painted Bride Art Center. The theater, which would ordinarily seat more than 200, was dark and empty but for a handful of volunteers. One by one the dancers entered and shook hands with Tiziou. After a reassuring smile, he would step back into the shadows, convincing them to ignore the camera and use their 10 minutes however they saw fit.

Without an audience, each performance was a remarkably intimate exchange.

“In some ways, dance is like the total opposite of photography,” he says. “They’re both very much about the moment, but photography is about being focused on the moment in front of you, outside of your body, whereas with dancing you’ve got to be really in the moment, really present in your body in a fleeting way that you then let go of. And then it’s gone, and that was that.”

To capture that fleeting essence of a dance move in a photograph, Tiziou has come up with some special moves himself.

“I like to push the image to where there starts to be some blur, but this makes the shooting more challenging,” he says. “I have to constantly make choices about whether I stay still and let the dancer move through the frame, or whether I move with them to get half of it in focus, half blurred.”

To some observers, he almost appeared to be dancing with his subjects.

“JJ made me feel free to just move in what I was feeling,” says Rebecca Savage, who performed a “praise dance” to contemporary gospel music. “He gave just as much energy as I did, if not more.”

Monica Herrera, a dialysis-clinic administrator who danced to a traditional flamenco rhythm, was similarly impressed: “When I saw him in the dark, with his camera wrapped around his neck, his sweaty brow and his shoeless feet, I thought, ‘Now this guy is really living this experience!’”

According to Jane Golden, who also teaches an interdisciplinary class at Penn on mural arts, Tiziou “knocked the competition out of contention” with his energetic and inspiring affect.

“JJ is not only an extremely gifted photographer,” she says. “He is a wonderful human being—full of insight, kindness, and a strong feeling that his work should capture the artist and dancer in us all.”

Tiziou spent another hour cajoling his behind-the-scenes volunteers onto the stage to be photographed after the official shoots concluded. (Full disclosure: The author of this article was unable to resist.) The unlikeliest dancers have yielded some surprisingly striking images. Tiziou all but refuses to acknowledge the concepts of embarrassment or self-consciousness.

“Some public art is like—Okay, this is art, and it’s for us,” he says. “Or it’s about us. Or it’s nice to look at when you walk by. Whereas what I’m about is art that comes from us.” He’s speaking quickly again. “That’s what’s so great about this project, you know? All of us made it. And all of us can see ourselves in it.”

—Rachel Estrada Ryan C’00