I have Fraggle Rock DVDs on my shelf, The Muppet Show theme song in my head, and two Avenue Q playbills stashed somewhere in my basement. I tell you that not to impress (or frighten) you, but to make you aware of an important fact about me: I like puppets.

Sadly, as an adult living in 2011, my daily exposure to puppets generally hovers around zero. (Especially since Avenue Q closed.) That said, I’ve been looking forward to a Penn Humanities Forum spring event titled Puppets: The Original Avatars ever since I heard about it several months ago. (The event was also a part of Philadelphia International Festival of the Arts (PIFA) 2011, which runs through May 1.)

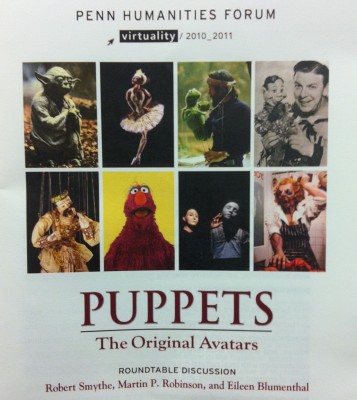

Here’s the description Penn provided:

For thousands of years, puppeteers and their audiences have known what Hollywood still hasn’t quite mastered: how to breathe life into the inanimate to create a consistent reality. Puppets have historically served as the middlemen between humanity and its gods, inviting viewers to reimagine the world long before motion pictures and computers did. As live theater and cinema battle for audience, what role does the puppet play on stage and on screen? While technology races forward, creating new ways of defining experience, one question sums up the issues: was the puppet Yoda in the original Star Wars saga better than his digital representation in the later movies?

Join us for a a romp through the world of puppetry old and new, using video and live performances in this roundtable discussion featuring reflections, anecdotes, and analysis from some of the world’s most notable scholars and practitioners of puppetry.

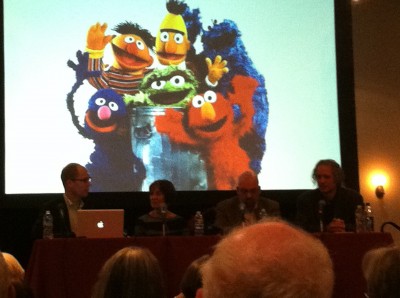

And so, after several months of anticipation, I found myself inside Houston Hall’s Bodek Lounge last night with about 125 other puppet enthusiasts, waiting to hear from some of the country’s foremost puppet experts and wondering what sort of live performances might lie ahead.

Moderated by English Professor/Penn Humanities Forum Director Jim English, the discussion panel consisted of:

- Robert Smythe, founder and artistic director of Mum Puppettheatre — the only regional theatre in the country devoted to puppetry. (Sadly, it closed in 2008 after 23 years of puppet performances.)

- Martin P. Robinson, a professional puppeteer who has worked on Sesame Street since 1981 (he’s performed as Snuffleupagus, Telly Monster and Slimey the Worm) and who designed, built and performed the plant in the original off-Broadway production of Little Shop of Horrors in 1982.

- Eileen Blumenthal, a professor of theatre arts at Rutgers University and the author of Puppetry: A World History.

It was a dynamic group, and English’s first question — What exactly is a puppet? — led to a lengthy discussion among the panelists. Smythe said a puppet is “an inanimate object manipulated so that the audience believes it thinks,” while Blumenthal defined it as “when an inanimate object is endowed with life and cast into a scenario.” All three panelists agreed that it’s not an easy term to pin down, especially in the age of digital (i.e. CGI) puppets.

Definitions aside, Robinson said he greatly prefers the original Yoda puppet in Star Wars to the more recent computer-animated one. He also noted that the original Yoda was both voiced and puppeteered by only one person–Frank Oz of Muppet Show and Sesame Street fame–creating a complete, single-source acting performance that doesn’t happen with today’s swarms of computer animators. (Robinson also said the Sesame Street group affectionately refers to the original Yoda as “Groda,” because Oz’s voice for him was similar to the Grover character he’d created on Sesame. See what you think here.)

Smythe, who teaches puppetry at Temple University, discussed some of the research that’s taking place around puppets. Asked whether they’re more accurately described as children’s entertainment or high art, he said there is no doubt puppetry appeals to children, but that a cognitive development study he’s been working on has found something more surprising: “Now we actually have hard data that backs up that when people watch puppets, there’s something in the limbic part of the brain that actually fires and gets us excited,” he said. “It happens no matter how old you are…there’s something that’s actually physiologically happening in the human brain that enables an instant connection with puppets.”

Smythe also mentioned another puppet-based study that has found that a four year old can determine whether a puppet is manually or electronically operated based only on a four-second video clip.

He later noted that puppetry “is no more threatened than live theatre is threatened,” and criticized the notion of putting puppets in museums. He said the latter is akin to going to an art museum to stare at the artist’s paintbrush; in both puppetry and painting, the product is the painting or performance, not the tools used to produce it.

Following still more back-and-forth chat about what constitutes a puppet (do cartoons count? dolls? dummies? masks? dog toys?), an audience member asked the panelists what they would have liked to talk about that night, had there not been so much time spent on defining a puppet. Here are their answers:

[youtube height=”HEIGHT” width=”WIDTH”]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JPcUKDjzGyU[/youtube]

And finally, in the moment we’d all been waiting for, Robinson introduced several of his puppets, including a retired version of Telly Monster:

[youtube height=”HEIGHT” width=”WIDTH”]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6Hni429GzSc[/youtube]