For several alumni, the grueling Minor League Baseball journey is worth it—even if the majors never call.

When he had coffee with Matt O’Neill W’19 last year, Peter Hissey W’19 could have focused on the four concussions he suffered on a baseball diamond. Or the long bus trips and low salaries synonymous with Minor League Baseball. Or all of the things he missed out on while playing in the Boston Red Sox organization for seven years before getting cut loose and going to college almost a decade after his friends had.

But Hissey had a more uplifting message for O’Neill, a standout catcher on the Quakers. “The biggest thing he emphasized,” O’Neill recalls, “is how cool it was to play pro baseball. And being in the kind of environment that Penn is, you don’t always hear that going to not make a lot of money, and play baseball around the country, would be a marquee job. It definitely gave me a little more confirmation.”

His initial trepidation made sense. Unlike a lot of his Wharton classmates, O’Neill didn’t have a job lined up when he accepted his diploma this past May and hadn’t even thought about careers beyond baseball. But two weeks after anxiously donning his cap and gown for the University’s Commencement, O’Neill was selected by the New York Mets in the 20th round of the 2019 Major League Baseball Draft.

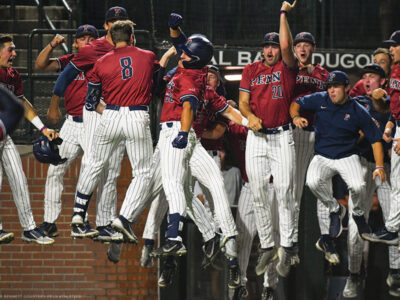

“I knew I wouldn’t have slept a night if I didn’t try to play pro ball,” says O’Neill, who became the seventh Penn baseball player drafted in the last five years. Of those seven, Jake Cousins C’17, Billy Lescher C’18, and Austin Bossart C’15—who joined O’Neill in the Mets organization after the Philadelphia Phillies traded him on June 29—remain active in the minor leagues.

Two days after the draft, O’Neill flew to Florida, signed a contract, was shipped off to Kingsport, Tennessee, and then back to Florida to play for the Gulf Coast League Mets. If he performs well on those Rookie League teams, he can potentially climb the rungs of Class A, Double-A, and Triple-A to reach the ultimate destination of Major League Baseball.

But he knows it’s a long road that bends insistently away from big-city glamour, and that he can be cut or traded at any time. Still, he’s already cherishing the camaraderie built with teammates in the same situation. “You become really close with a guy you had no idea existed two weeks before,” O’Neill says. As for the starting salary of $1,100 per month (which is just $59 over the poverty line and is only paid during the season), he notes, “My goal is not to make a lot of money as a Minor League Baseball player. My goal is to make it to the major leagues.” The MLB minimum is $555,000 per year.

Bossart, a defensive specialist at catcher, may have the best shot at being the first Penn alumnus since Mark DeRosa W’97 and Doug Glanville EAS’93 to reach the majors. The recent straight-up swap that sent him from the Phillies to the Mets for MLB starting pitcher Jason Vargas potentially shows his value (at least from the Mets’ perspective). And even though his batting average has dipped in 2019, he’s become an everyday player at the Double-A level.

Yet it’s an uphill climb. According to a recent study done by Baseball America, only 17.6 percent of the players who were drafted and signed between 1981 and 2010 ended up making it to the majors. And the odds dip even more for players drafted after the 10th round. A 14th-round selection, Bossart was the highest draft pick out of Penn since DeRosa and Glanville—but still lower than most eventual big leaguers.

“That’s something I’m very realistic about,” says Bossart, whose biggest challenges in the minors have been adjusting to playing every day and being away from his wife, a vet tech in St. Louis, during the season. “I’ve got to realize there are other things I need to do with my life at some point. But it’s a special thing being able to play professional baseball, so I’m definitely taking full advantage of it for as long as I’m able.”

Bossart adds that having a Penn degree “makes it a little easier to keep sticking it out because I know in the future I’ll be just fine.” And Hissey furnishes proof of the good things that can happen after baseball.

A fourth-round pick in the 2008 draft, the outfielder bypassed a college scholarship to the University of Virginia to sign with the Red Sox directly out of Unionville (PA) High School, in large part due to a $1 million signing bonus (a benefit of getting drafted in the early rounds). But it was still a difficult decision because the idea of college life appealed to him. So when he wasn’t re-signed after his initial seven-year contract with the Red Sox expired, he retook the SATs, reconnected with the Unionville High guidance counselors, and applied to three colleges: Harvard, Princeton, and Penn. He got into Penn, and “wanted to make up for it all,” he says. So he took at least six classes every semester, was a mainstay at professor office hours, joined financial literacy clubs, became a Wharton Ambassador, and graduated in three years with a 3.92 GPA last May.

Hissey, who’s married and didn’t live on campus, recalls being mistaken for a teaching assistant at times. “I was really involved between the hours of 8 a.m. and 6 p.m. and the rest of the college experience I didn’t get … I almost got a parent’s dream of a college education.”

Most of his classmates and professors didn’t know he was a former pro baseball player—“I was a ghost on campus,” he says—but he often thought about his Red Sox days, and how he made it as high as Triple-A without getting that coveted final call-up. “I would have loved to have played in the big leagues, I would have loved to have played at Fenway [Park],” he says. “It’s a dream that didn’t happen for me.”

But that didn’t mean the seven-year journey through the minors wasn’t worth it. “When I think back on my best memories, it’s all of the off-field stuff,” says Hissey, who, interestingly enough, was on Penn’s campus around the same time as another former top prospect who never made it to the majors, Chris Lubanksi LPS’16 GEn’17. “The bus trips. The locker room. The rain delays. The cancellations. It’s being able to bond with people. In this incredibly intense environment, you make friendships really quickly.”

And those friendships, Bossart claims, are actually bolstered—and not hurt—by the fact that everyone is gunning for the same thing in the end. “Everyone’s rooting for everyone else,” the 2015 co-Ivy League Player of the Year says. “I’ve had quite a few teammates to go up to the big leagues. And every time it happens, it’s one of the coolest things ever.”

Will a Penn alum get there? Recently, Bossart and Lescher played against each other in a Double-A game. (Penn coaches marked the accomplishment by attending the contest.) O’Neill never played with Bossart at Penn but says that Lescher, a relief pitcher in the Detroit Tigers organization, is one of his best friends and an inspiration. Now he hopes to follow the same serpentine path.

“As of now, I plan on playing until they tell me I can’t play anymore,” says O’Neill, who led the Ivy League with a .405 batting average in 2019. “Until I make it to the major leagues, I don’t think I’d be fully satisfied.” —DZ